“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-first century.

Silenced voices of disappeared dissidents and migrant slaves. Melodies lost to the violence of empire. Vanished monuments marking anti-colonial choruses. Hidden, transgressive dances of migrant domestic workers. Inaudible and obscured, these sounds and movements haunt Hong-Kai Wang’s work. Rather than erecting monuments to these pasts, Wang uses listening, sounding, and singing as conduits to these lost or absent acts across temporal and geopolitical distances. This practice, situated around sound both real and imagined, might be described as anti-monumental.

“Sound art” is the category often ascribed to Wang’s pieces. But more accurately, the primary medium of her work is the act of listening. Wang uses workshops, collaborative listening sessions, and open rehearsals to develop her projects. Collective listening and the physical effort of speculative hearing harbor the possibility of remembering and reconnecting to the silenced past. The work of remembrance happens in the space between the listeners and the past histories that they invoke.

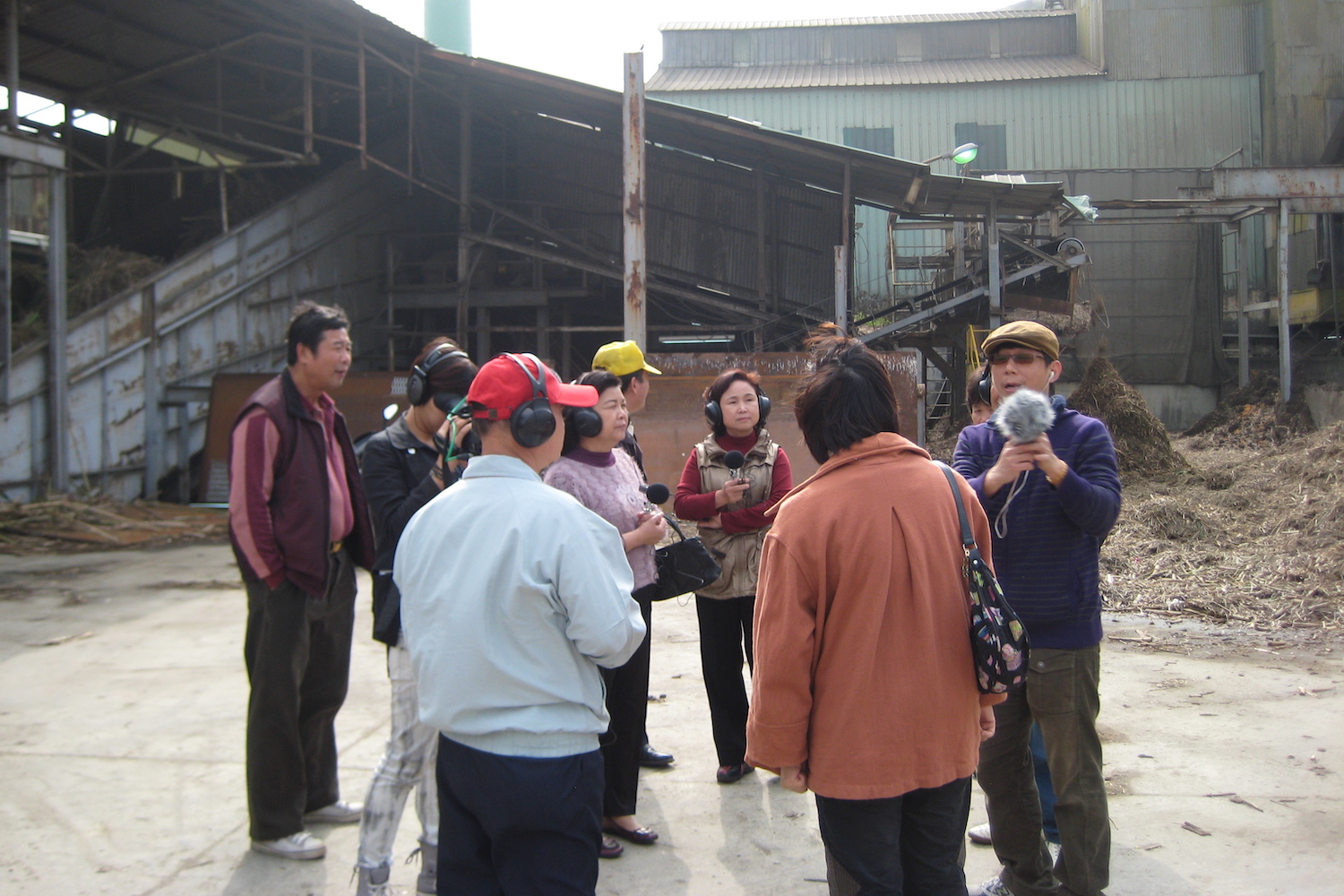

Documentation of Wang’s past projects includes a sizable number of images of people listening in groups. For Music While We Work (2011), in Huwei, Taiwan, retired factory workers and their spouses gather on the grounds of a sugar mill. They wear black headphones and hold microphones attached to portable recorders. After they receive prompts for recording and instructions on using the equipment, they walk through the sugar factory to record the sounds of their work. The resulting soundtrack and film from the recording workshop sessions draws attention to the mundane sounds of work of generations dating back to the days of Japanese colonial rule.

At a workshop for her piece Southern Clairaudience (2016–), a group of sugarcane workers and their families in the rural Dongshih township in Taiwan gather around a table at the plantation’s office. They look intently at a sheet of paper. The sheet contains the lyrics of the “Sugarcane Song,” written by the workers during what was the first anti-colonial class-conscious agrarian uprising in 1925, when Taiwan was under violent Japanese colonial rule. Given the extraordinary significance of the event, it’s surprising that the melody is lost; only the lyrics remain. Toward the end of the workshop, the group writes and sings a new melody together. The fact that a modest wooden monument that once stood among some weeds next to a plot of farmland in Erhlin, Taiwan, collapsed as of 2017 makes Wang’s work all the more critical (a group of local elementary students had re-erected it in 2018). Through the work of listening together, Southern Clairaudience urges listeners to reconstruct “dissonant readings” of the “Sugarcane Song.” (The idea of “clairaudience” in the title of her piece is related to the more common notion of clairvoyance in that it seeks to “audition,” or hear, those sounds and voices that have been rendered inaudible.)

We invite you to listen “Hazzeh” sound excerpt:

In Hazzeh (2019), which means “quiver” as well as “earthquake” in Arabic, Wang deploys listening as a way of accessing the depths of sadness at the Jordan/Palestine border around Jericho, Ajloun, and the Dead Sea. In what Wang describes as an “open rehearsal,” a group of Palestinian and Jordanian women performers gather along the geological faultlines at the border. Facing the hills and valley of Ajloun, they utter lyrics extracted from the book Palestinian Mournings by Hassan Atari. As they perform, they recall their grandmothers’ ways of doing Nuwah, a ritual lament performed by women, long banned and barely documented. Walking further, their voices resound physically through one another’s bodies as well as the canyon rocks and cliffs by the Dead Sea, coaxing the landscape to release the ancient memories of conflict and loss. At the heart of this sadness is a sense of the unknowable, shared by Wang (as a cultural outsider) and the local performers (as modern interpreters of a historical form) — and perhaps by the lament performers of the past too, who performed because the actual depths of sadness were unknowable to them as well.

In this void of authoritative inscription — or this void of monumentality — Wang opens a space for reclaiming the relevance of Nuwah in the present. Framing an act of singing and listening together as a form of historical and speculative inquiry, Wang’s workshop process validates the women’s attempts as legitimate traditions in which the quivering affect of loss is no less real than in the performances by the generation of their grandmothers.

The scenes above are not the works themselves, but records that document events. Wang’s work resists inscription and precise documentation. This quality of anti-monumentality, the smallness or the intangibility of the acts of listening, is precisely its power, propelled into motion by the physical work of listening to sound. Because when monuments fade and the state archive is closed (or restricted), the lived practices, imagined song, and the embodied dances –– what Diana Taylor called the “repertoire” –– offer the possibility of survival through acts of listening. Wang’s work vividly evokes the past, but it is a past that comes alive through acts of speculation. That is, listening together serves as an intersubjective portal that can conjure, and remember, at times disassembling and reconfiguring what we understand about the past.

But this is no leisurely activity. Wang has tasked her listeners, singers, and collaborators with the never-ending, hard work of listening — with empathy, with curiosity, and with an ear toward future-oriented possibilities by listening to the past in the present: that is, making the invisible legible and the forgotten audible. Reformulating history, the archive, and remembrance into the domain of performance, acts of singing and listening articulate the ongoing need to allow the lives and struggles of voices on the brink of erasure to be heard. Wang’s workshops in this sense are simultaneously forms of work (as in work songs), practices of resistance, and processes that attempt to decolonize historical narratives and their monuments by imagining and creating new conditions of possibility for the past. Listening in this way situates resistance in mundane acts and gestures that reverberate in the layered soundscape of everyday life, interwoven with sounds of machinery, prayer, nature, commerce, and leisure.

These histories of violence and erasure cast an unbearable weight. Yet, through acts of collective creativity, Wang’s workshops bring a certain lightness to the activity of collective listening and sounding that make it possible to confront them. What’s more, the connections forged through shared experiences of singing and listening make these histories an intensely personal matter. In the resonant space of listening there is vulnerability and pleasure in singing together, embarrassment at recognizing our failures, and joy in learning the successes of our abilities to hear beyond our isolated selves. Wang’s work offers a glimmer of hope in the ways that listening together can be a tactic for survival in the present.