As the plane neared its destination — the Maltese islands, just south of Sicily — I noticed tankers dotted around what looked like an unusually shallow stretch of seawater. Later I found out we were cruising above a vast offshore anchoring area known as Hurd’s Bank, apparently the largest in Europe, which lends its name to a captivating film by Tobias Zielony. The centerpiece of his solo show at Blitz, an artist-run contemporary art space situated in the heart of Malta’s capital Valletta, Hurd’s Bank (2019) was shot using a telescopic lens that accounts for a certain nebulous quality and the fuzzy round framing of the image. Seascapes and harbor views form a backdrop to stories of trafficking, smuggling, and piracy, read out by an actor in voice-over. “The telescope blurs the distinctions between distance and proximity, risk and safety, movement and stillness,” we are told at one point.

Best known for his photographic portrait series, a selection of which was also on view at Blitz, Zielony is an accomplished writer, mixing historical fact and journalistic findings, dream accounts and snippets of conversations with people he encounters on the island, to powerful effect. His film essay explores the unsolved mystery surrounding the brutal killing of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, whose incendiary blog Running Commentary targeted corrupt politicians at the highest level. A monument located on the side of the central St John’s Co-Cathedral, which holds Caravaggio’s Beheading of St John (1608) among its treasures, acts as a makeshift shrine where people still lay wreaths and light candles in memory of the murdered journalist.

The highly volatile political context lent added urgency to Zielony’s film. My stay on the island in mid-January coincided with the elections of the ruling Labour Party’s new leader and the surprise win of outsider Robert Abela, who took over as the country’s prime minister following the resignation of Joseph Muscat, his charismatic but increasingly embattled predecessor. Muscat was accused of mishandling the investigation into Caruana Galizia’s murder, in which some of his closest political allies and friends allegedly played a part.

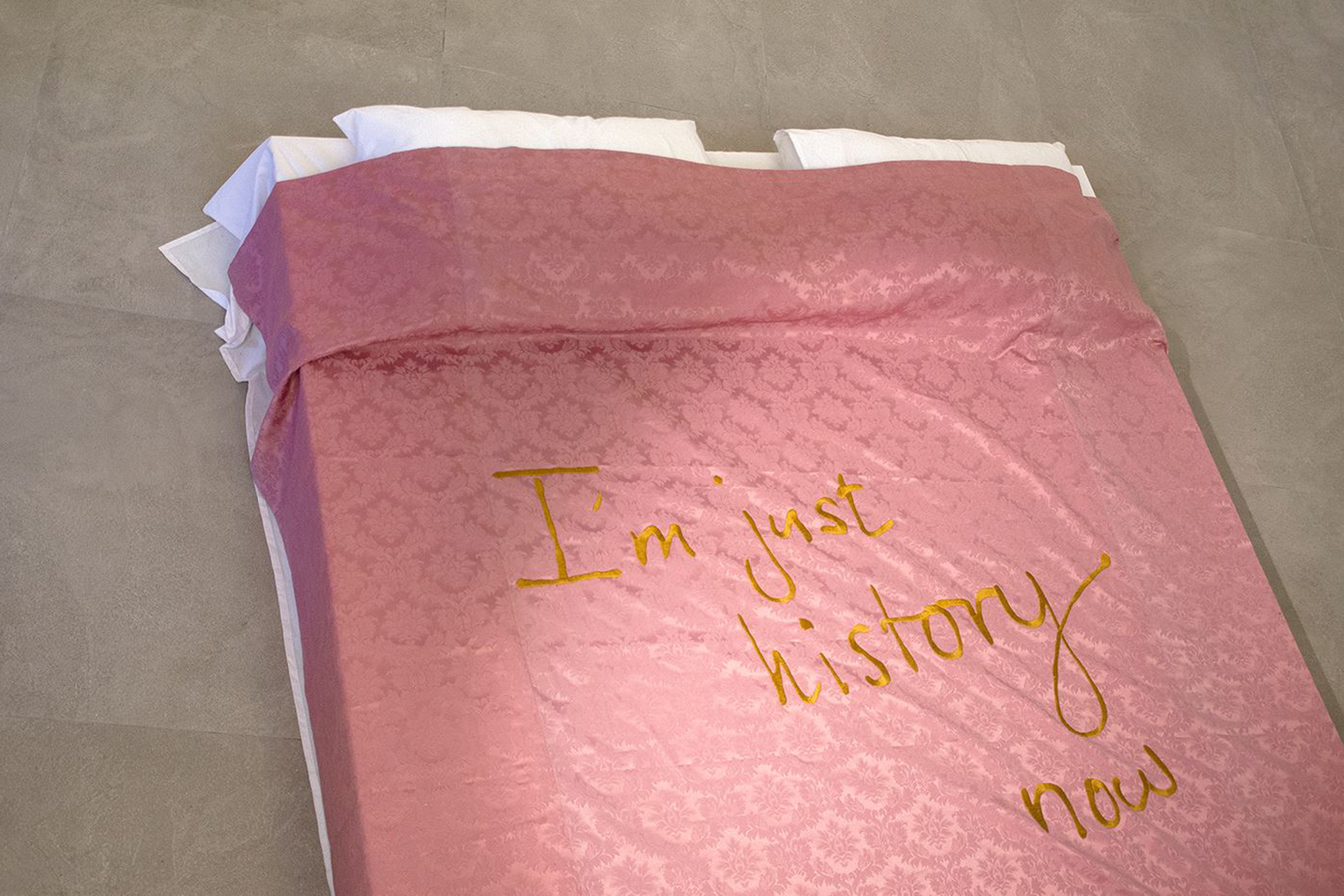

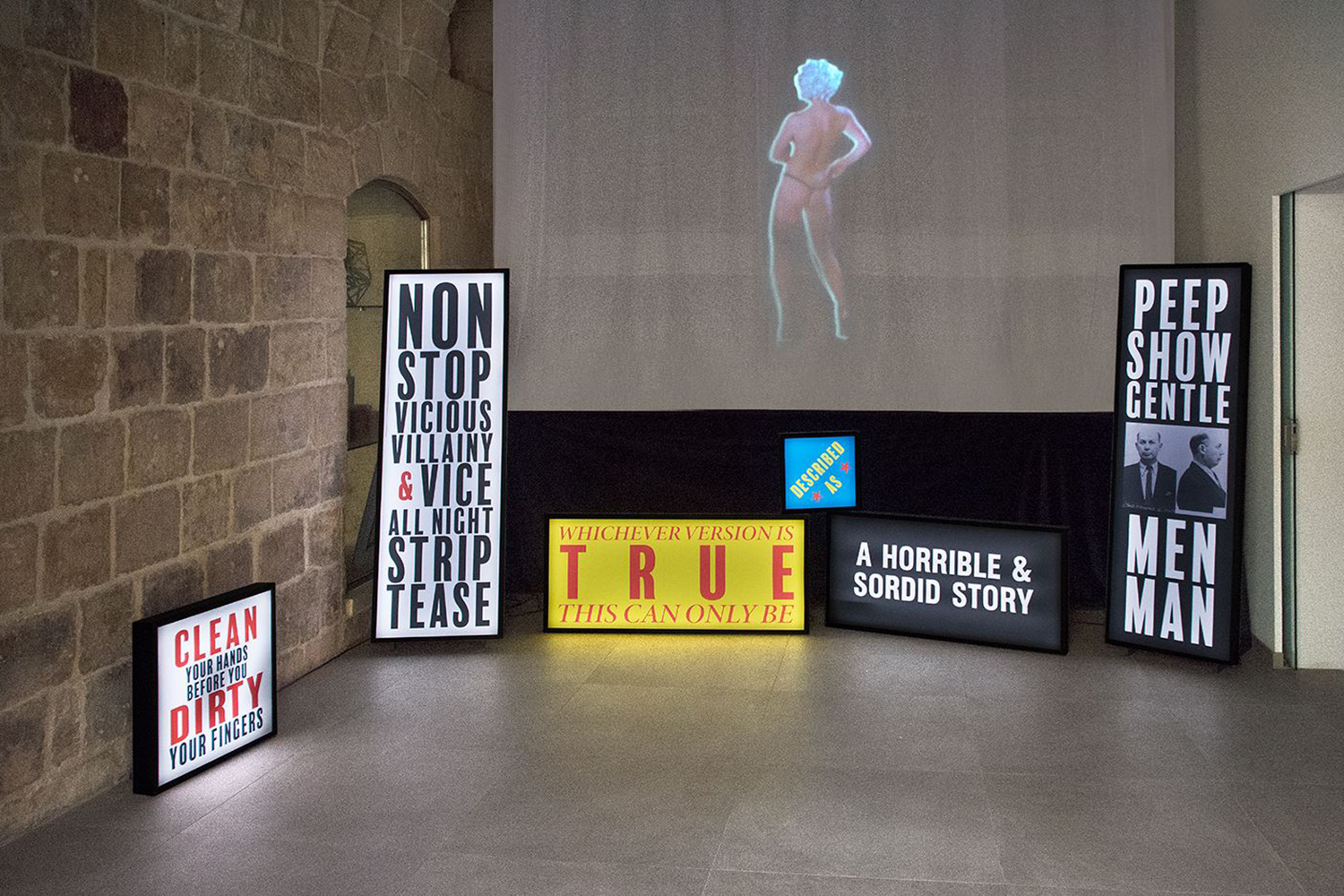

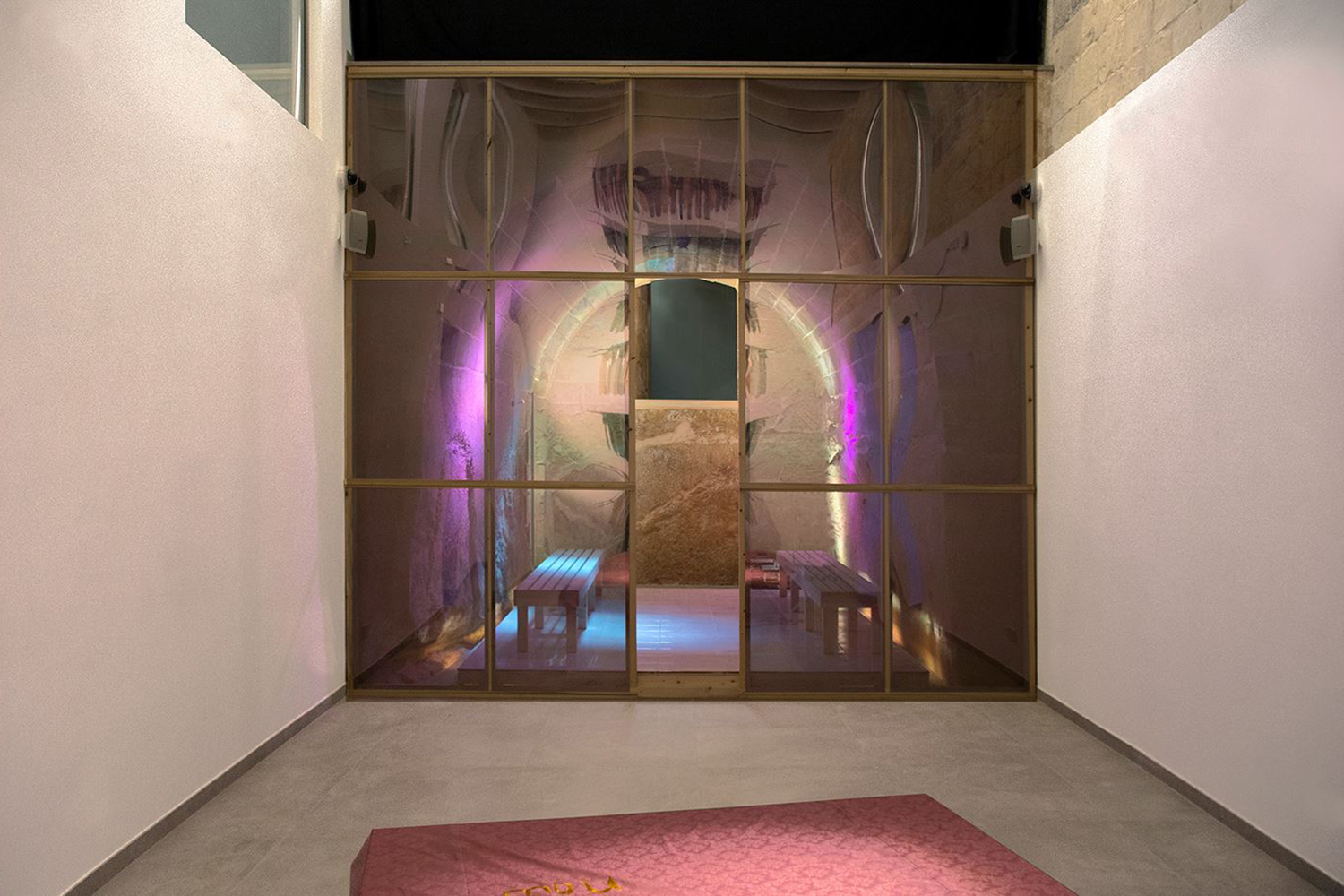

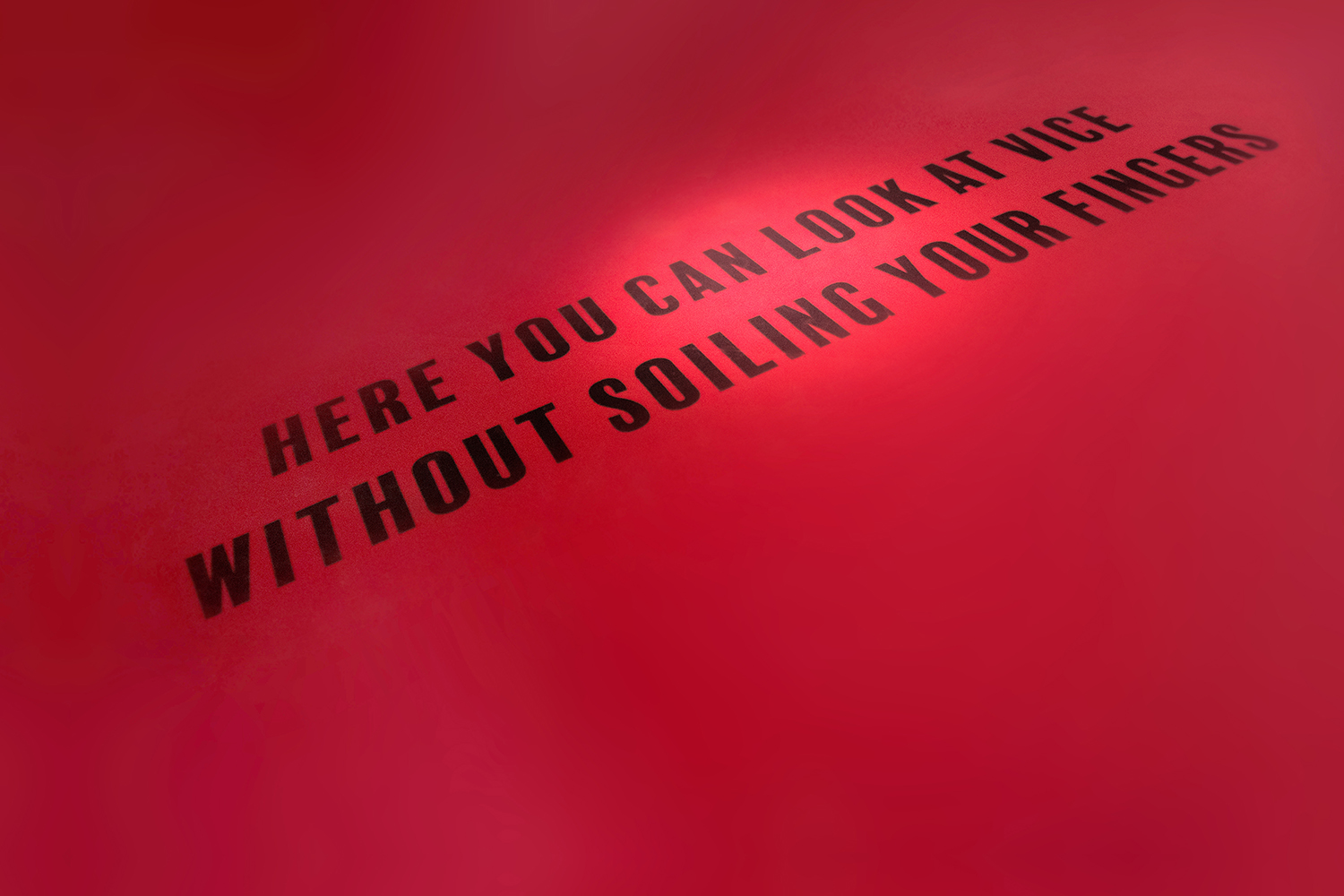

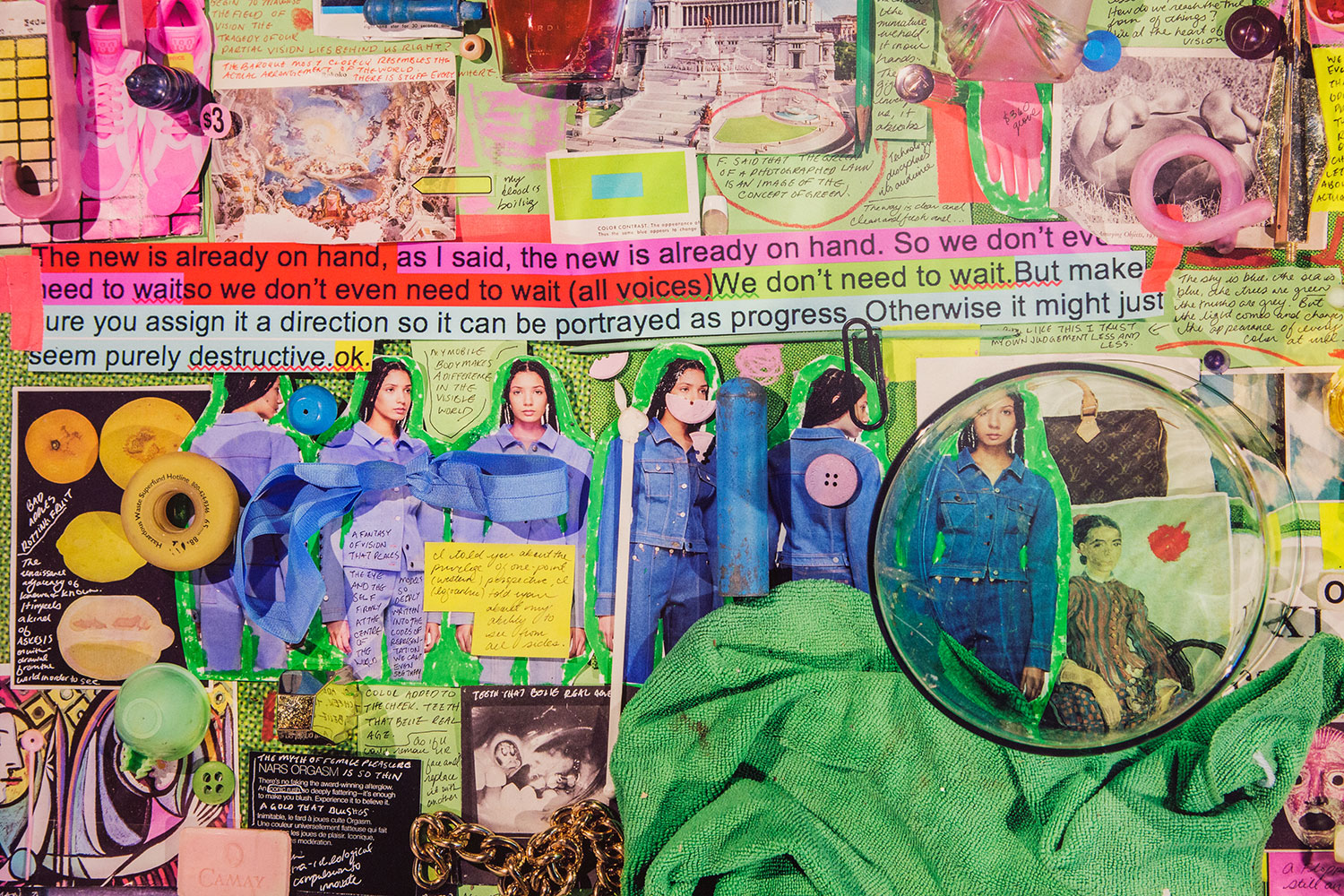

The narrator of Hurd’s Bank marvels at the romantic aura of smuggling and organized crime. Another show to address this was Charlie Cauchi’s “Scheherazade” staged at the commercial gallery Valletta Contemporary, one of the few places on the island where Maltese artists can exhibit (and sell) their work. Named after a Maltese-owned club that operated in London’s Soho district from the 1940s until the 1980s, “Scheherazade” conveys the seedy atmosphere of the place by means of titillating lenticular prints showing nude strippers descending a staircase, telltale neon signs, embroidered bedspreads, phallic velvet sofa sculptures, and crimson curtains — the kind that line the walls of baroque churches on the island. For Cauchi, these artworks emulate the club aesthetic but without its glamorous veneer.

Like many aspiring young Maltese artists, Cauchi chose to study in London instead of pursuing a fine arts degree at the University of Malta or vocational studies at MCAST (Malta College of Arts, Science & Technology), the two options open to art students at home. Brexit was the push she need to go back to Malta. “The smallness of the island is at once its difficulty and its strength,” says Cauchi. “Public funds may be limited, but there is more of a support network. Getting exposure outside of Malta is more tricky.”

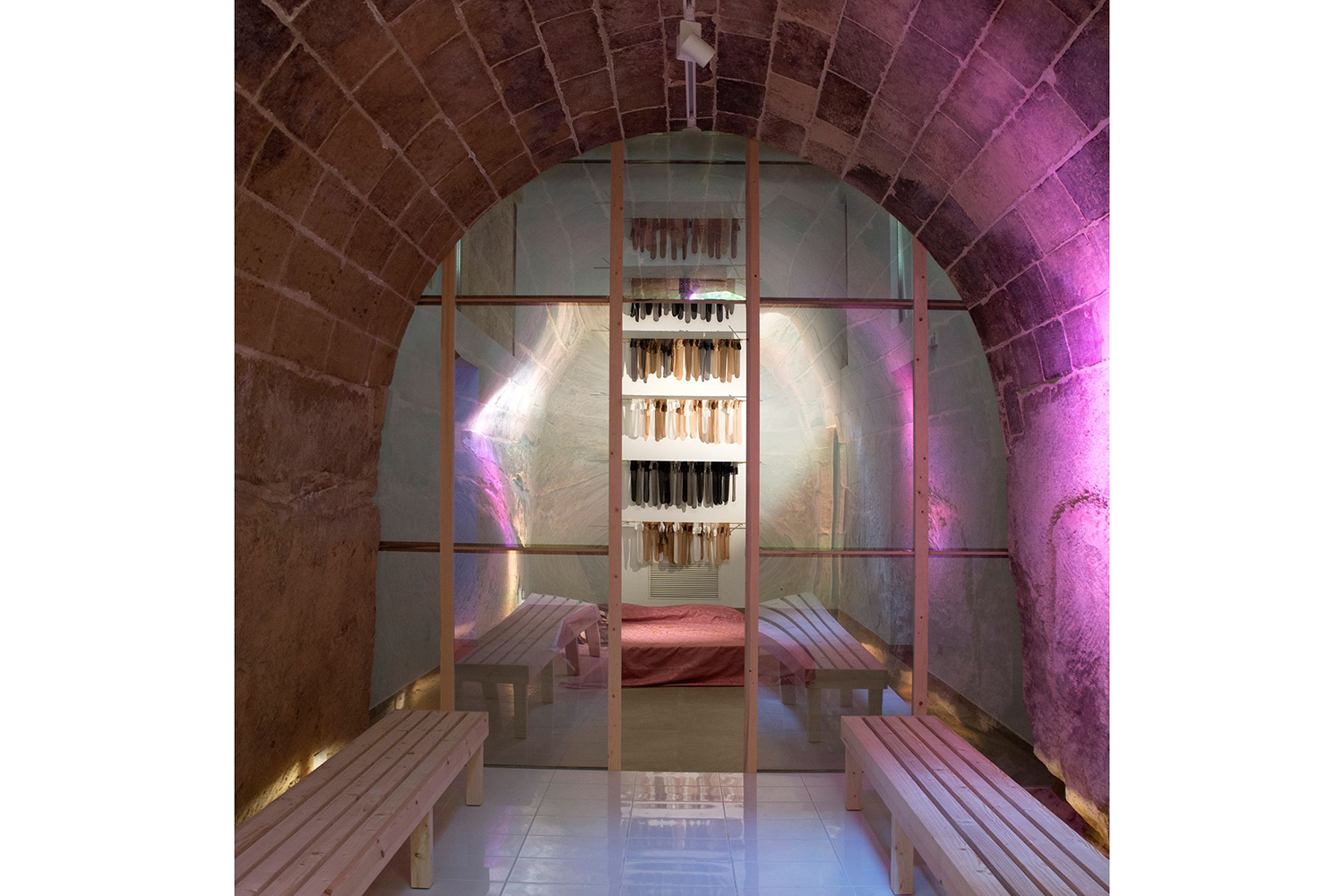

That is the gap Blitz is attempting to fill. Since the nonprofit opened its doors in 2013, at a time when the center of Valletta was undergoing a renaissance culminating in the city’s nomination as the 2018 European Capital of Culture, its founder, photographer Alexandra Pace, has tried out different models for nurturing the local arts scene. The current strategy is to use its gallery spaces mainly for exhibiting international artists while working closely with ten locally based artists on specific projects in Malta and creating opportunities for them to show their work abroad by connecting them to an international network of art institutions and patrons.

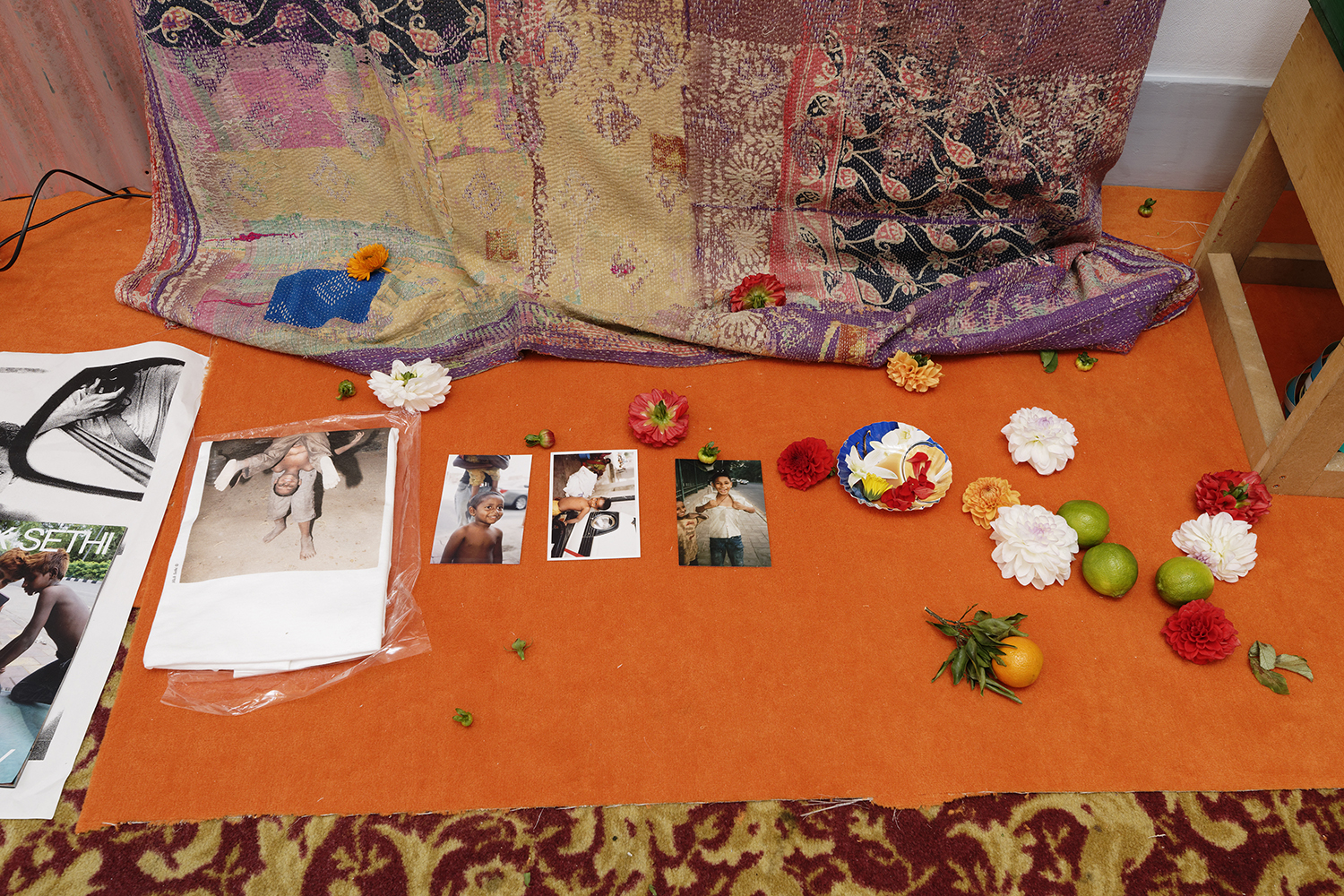

Cauchi is one of the ten artists to have benefitted from such support; Kane Cali, who also decided to return to Malta after spending nine years in the UK, is another. One afternoon, I visited his small workspace in St Ursula Street, which he rents for a bargain price from the Ursuline Sisters, who are his landlords. This, in addition to a lecturing post at MCAST, is what keeps him going. “Art is a practice of survival,” he tells me during the studio visit. Cali is nothing if not resourceful when it comes to making his art sustainable. A blue glass object cast in the shape of a sound wave that I spotted on a shelf turned out to be a trophy commissioned by the Arts Council. The newly opened Civil Service Sports Club has given him carte blanche to display his artworks on their premises in April. Designers David Gill and Francis Sultana, Malta’s “Ambassador of Culture,” collect his work; two days later I would see a sculpted head from Cali’s studio displayed in their Valletta home located on the same street.

What the city lacks is arguably a public museum dedicated to contemporary art. On my final day in Malta I got a tour of the building site of the eagerly awaited Malta International Contemporary Art Space (MICAS), set to open its doors in 2022. Instead of a new built, the MICAS board of trustees have set their sights on an existing complex of fortifications and bastions — the Floriana Lines whose construction bankrupted the Knights Hospitaller themselves — that was out of bounds to the public for the past sixty years. A team of international and Maltese architects are now facing the formidable task of reclaiming the lot and transforming it into a state-of-the-art museum.

“It is not just a building that makes a museum,” I was reminded by MICAS chairperson Phyllis Muscat, a force of nature by all accounts, which is what the project needs to get off the ground. For the time being, her team is busy building bridges with international art institutions like the Serpentine Gallery, organizing art talks and events, and unveiling outdoor sculptures by the likes of Ugo Rondinone and Pierre Huyghe. These take some looking after, as I discovered on the last stop of our tour: the outlying Buskett Gardens. Since October, these are home to Huyghe’s Exomind (Deep Water), a title that pretty much sums up the state of mind of the disgruntled beekeeper entrusted with its care. Whereas the bees were kept indoors in the dead of winter, the same could not be said for young troublemakers. Ray had to tell three of them off, then and there, for assailing the defenseless female effigy with ripe oranges.