Quinn Harrelson: Tell me about your exhibition “On Venus” at the Serpentine.

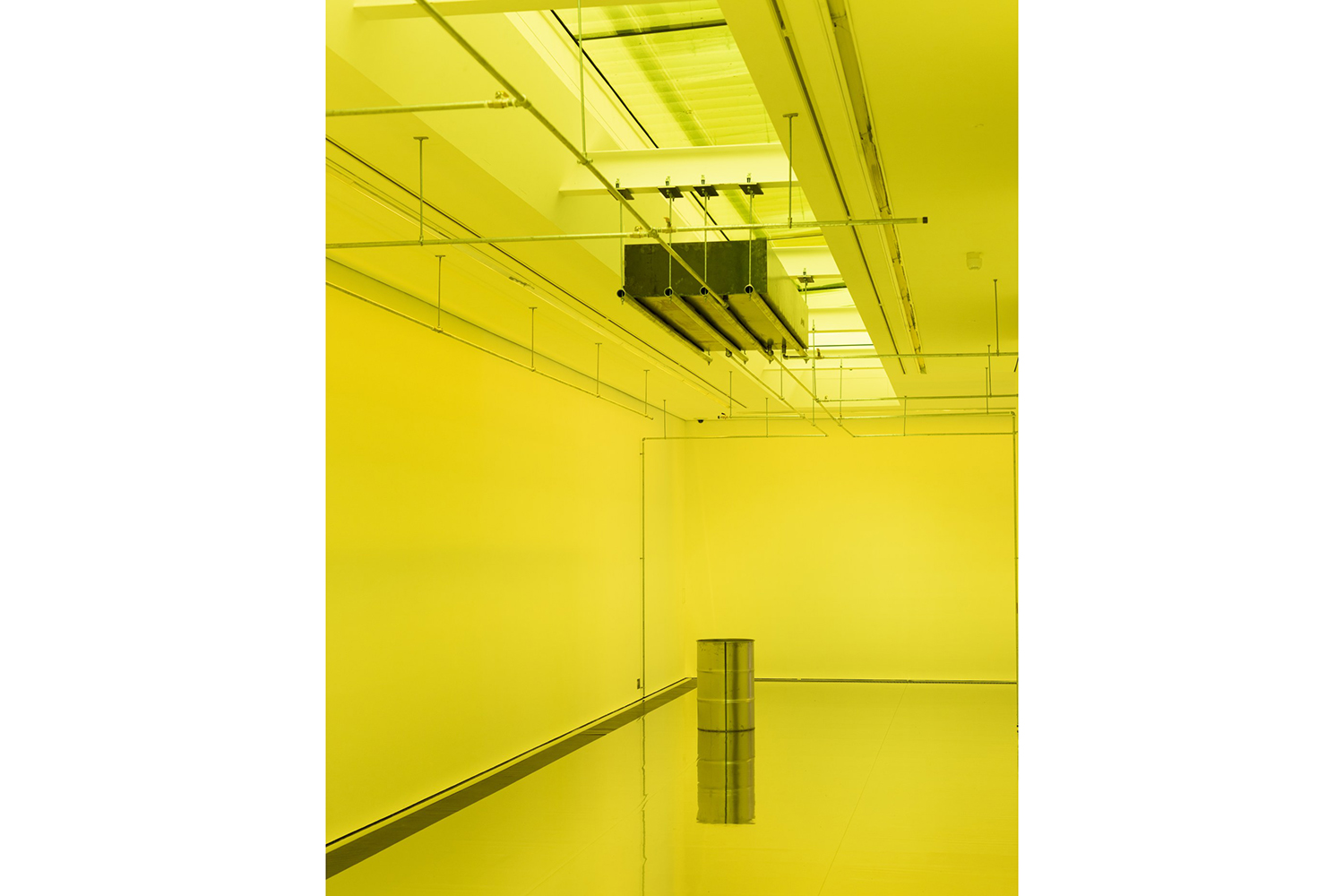

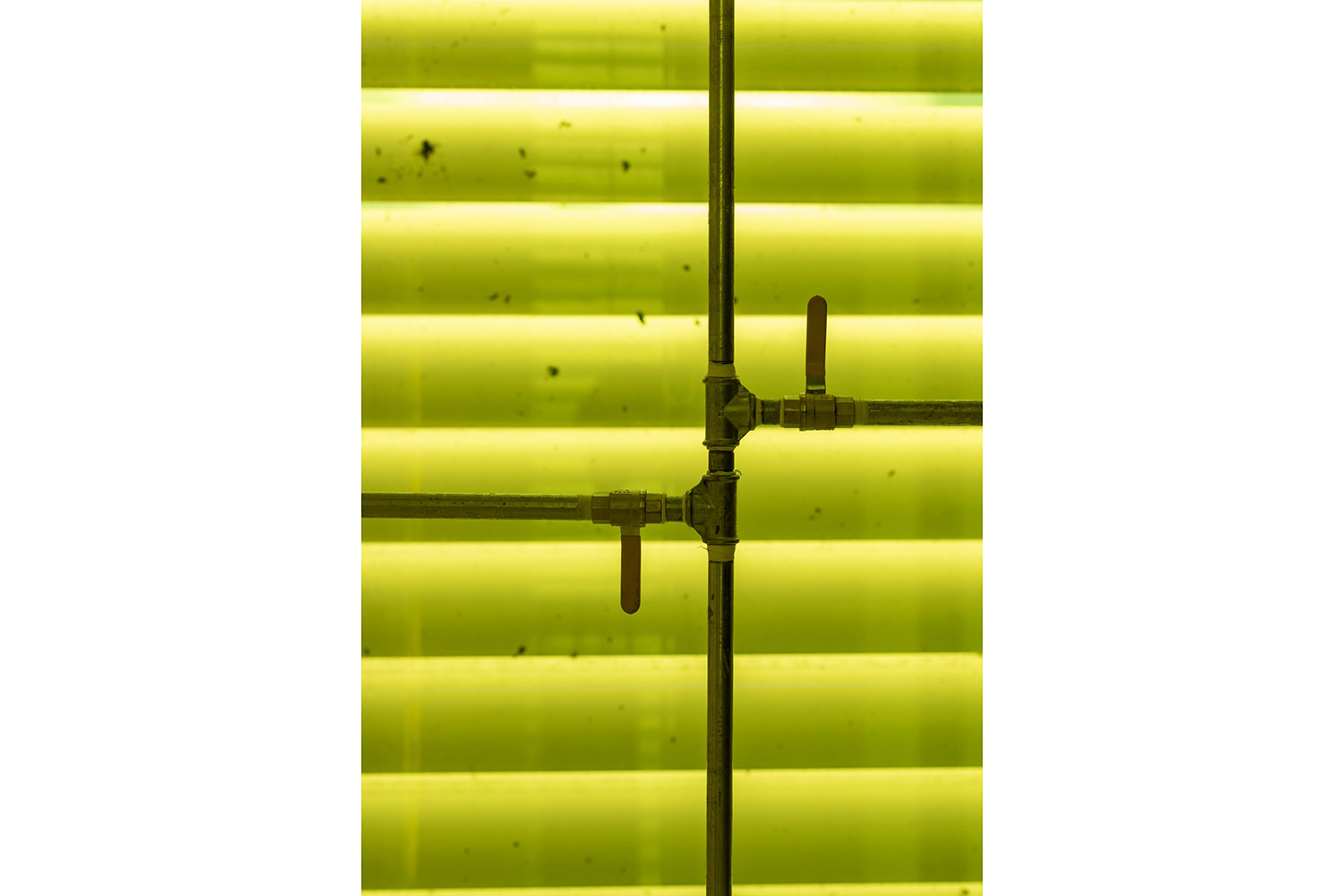

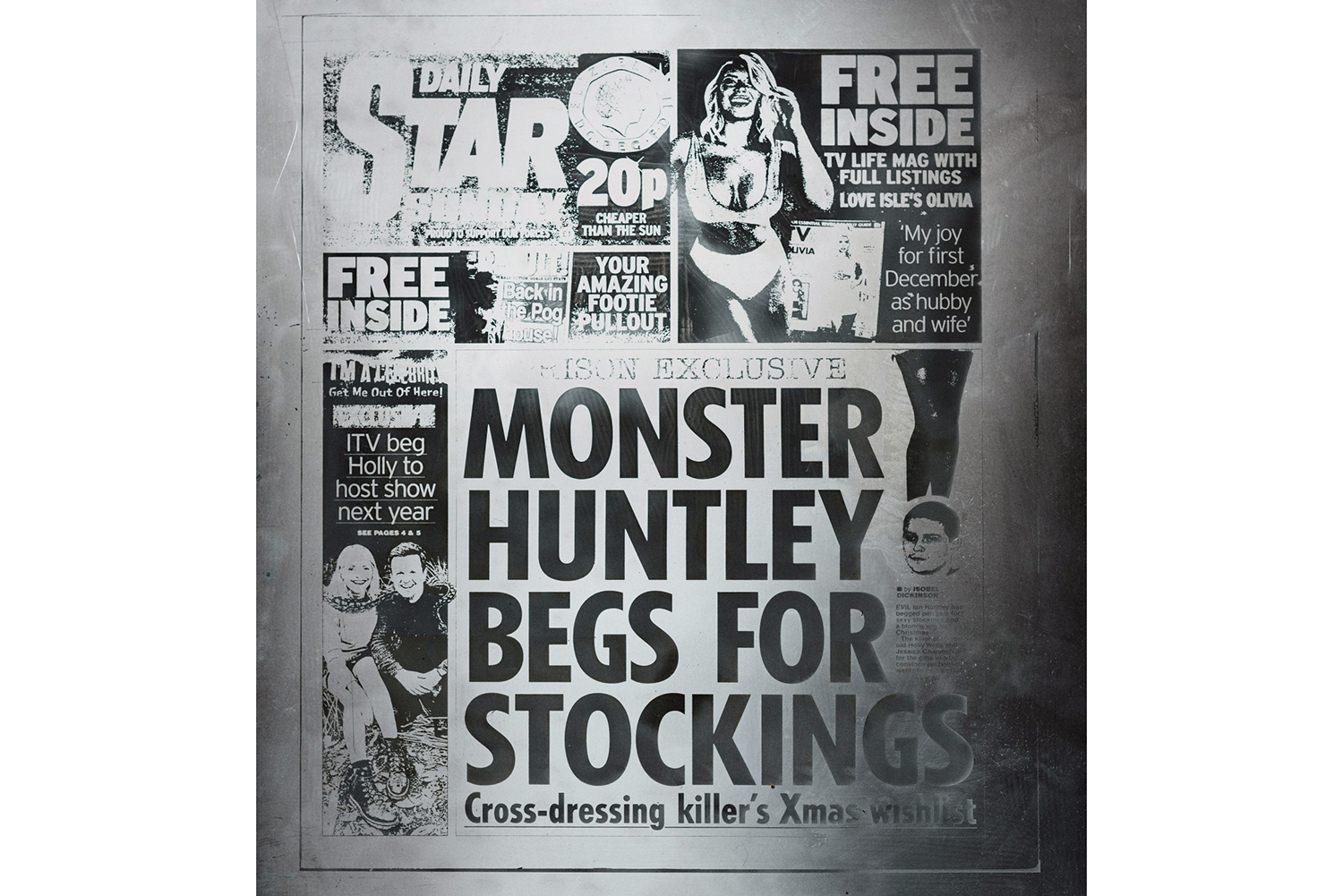

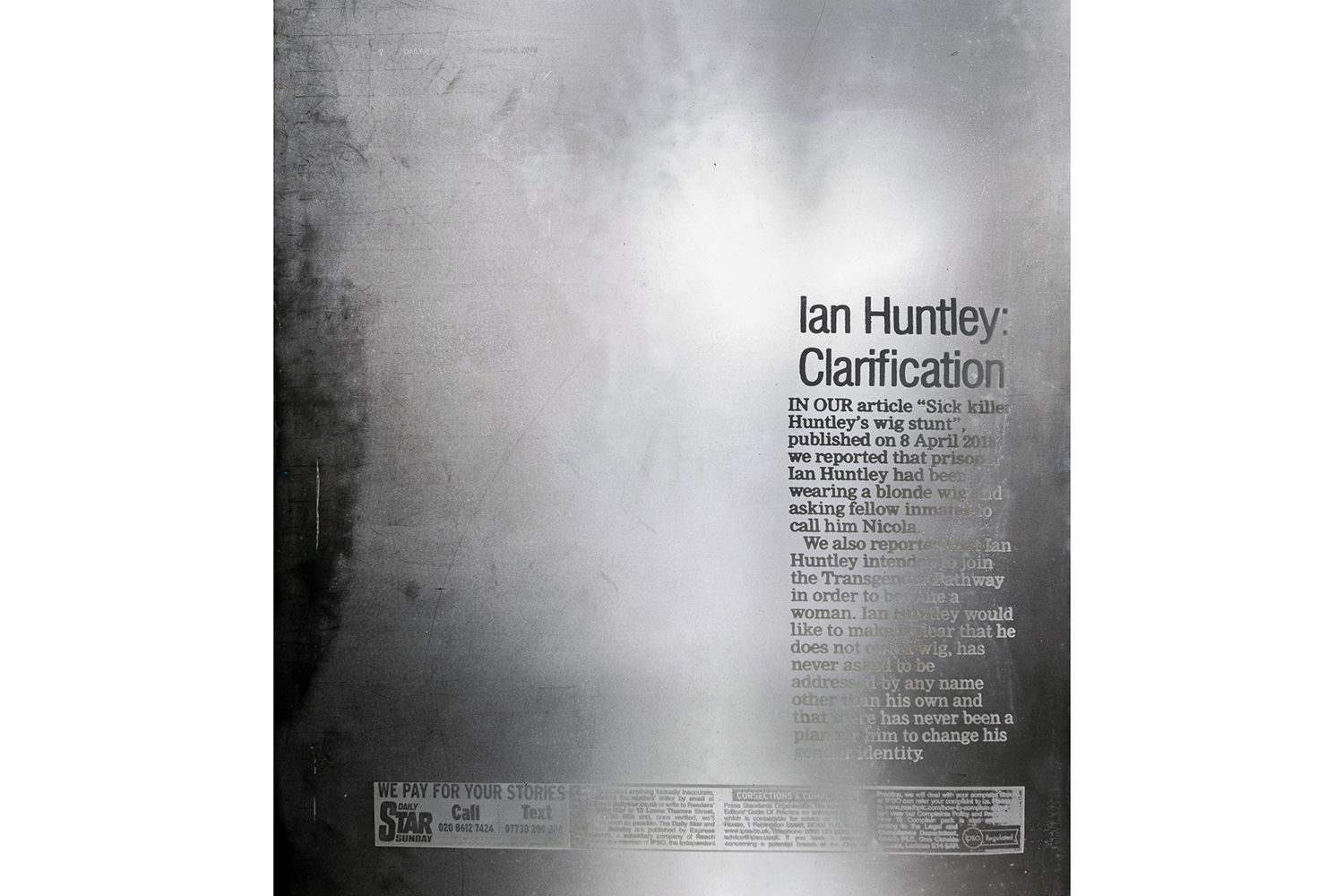

Patrick Staff: It’s all new work. Although it was always made with the intention of being one large site-specific installation, there are discrete constituent parts. There is a kind of architectural installation in which we have installed new flooring in the gallery and have adapted all of the lights, and then in the ceiling of the gallery we have built a kind of network of pipes and barrels, a sort of ad hoc plumbing system, that is leaking and dripping into the main space. What is leaking from the ceiling is a mixture of primarily two types of acid: one that is made in your body, produced in your muscles, and then another type that is synthetic. So there is this acid rain or leakage coming from the ceiling of the galleries and being collected and accumulated in these large barrels. And then there is one exhibition area that has an installation of large steel intaglio etchings, which is a type of etching where the metal is washed with acid in a sort of relief to produce a plate. Generally in this type of printing the plate is what you make the prints from, so you would put the ink and the paper onto the plate to make it, but in this instance we are showing all of these steel plates positioned on this grouping of boxes. They are all leaning or stacked at different heights and different sizes.

QA: What are the etchings of?

PS: The etchings depict a recent series of news stories in the UK. In 2017 and 2018 a number of tabloid newspapers began to run a story about Ian Huntley, who in the UK is a widely known murderer. Huntley killed two children in the early 2000s and is serving a life sentence. But for me, growing up in the UK, he seemed to be routinely summoned by the media as a figure of absolute evil. In the latest group of news stories that began to circulate it was said that Huntley was planning to transition or was looking to access gender services in prison. As is typical of tabloid reporting, the stories that were published were given headlines like “Evil Child Murderer Demands Stockings” or “Sick Monster Wants Wig.” The subtext in these stories was that this intrinsically evil individual was trying to use gender reassignment to somehow inflict further harm — that he wanted to be in women’s prison so he could be in closer proximity to people that he could hurt. The other narrative or implication was that this would be at the expense of British taxes, of public money. So there was always this phantom saying this what you are paying for, what you as a taxpayer and a good citizen are funding: a totally monstrous transformation.

The story gained traction and more papers began to run the story, yet once it was fact-checked it was found to be completely fabricated. Huntley released a statement saying that it was untrue. The prison where he is incarcerated released a statement saying that it was untrue. And then all of the newspapers that had published the story were obliged to either run retractions or clarifications or, in the case of online reporting, to amend or to fully remove the news stories from the web. So the etchings that I’ve made reproduce not only the headlines but also this string of retractions, clarifications, or outright deletions — websites with placeholder pages that say something like “what you are looking for is no longer here.”

QA: What is your interest in Huntley and the story concocted about him?

PS: What was making me want to work on these stories was a desire to reflect on this vicious moment in British media, not just in relation to the lives of trans people but also representations of incarcerated people, and also just this sex panic I was observing. I thought it was similar to what we saw with gay people in the early ’90s, when scare tactics or a kind of moral panic were employed to ultimately reinforce sexual and social norms, to further stigmatize queer individuals and to maintain a status quo. These stories were being produced at a time when trans people were fighting for reforms to the Gender Recognition Act, or for greater access to public resources, so it felt like there was this really clear line being drawn for trans people in the UK now. It speaks to these questions about who is allowed to live and under what conditions — questions about what are the implicit forms of violence and antagonism that are imbedded in the desire for self-actualization, and the implicit forms of dehumanization that occur in tandem with the fight for the most basic forms of dignity, which appear to me, as a trans British person, so central in the public psyche.

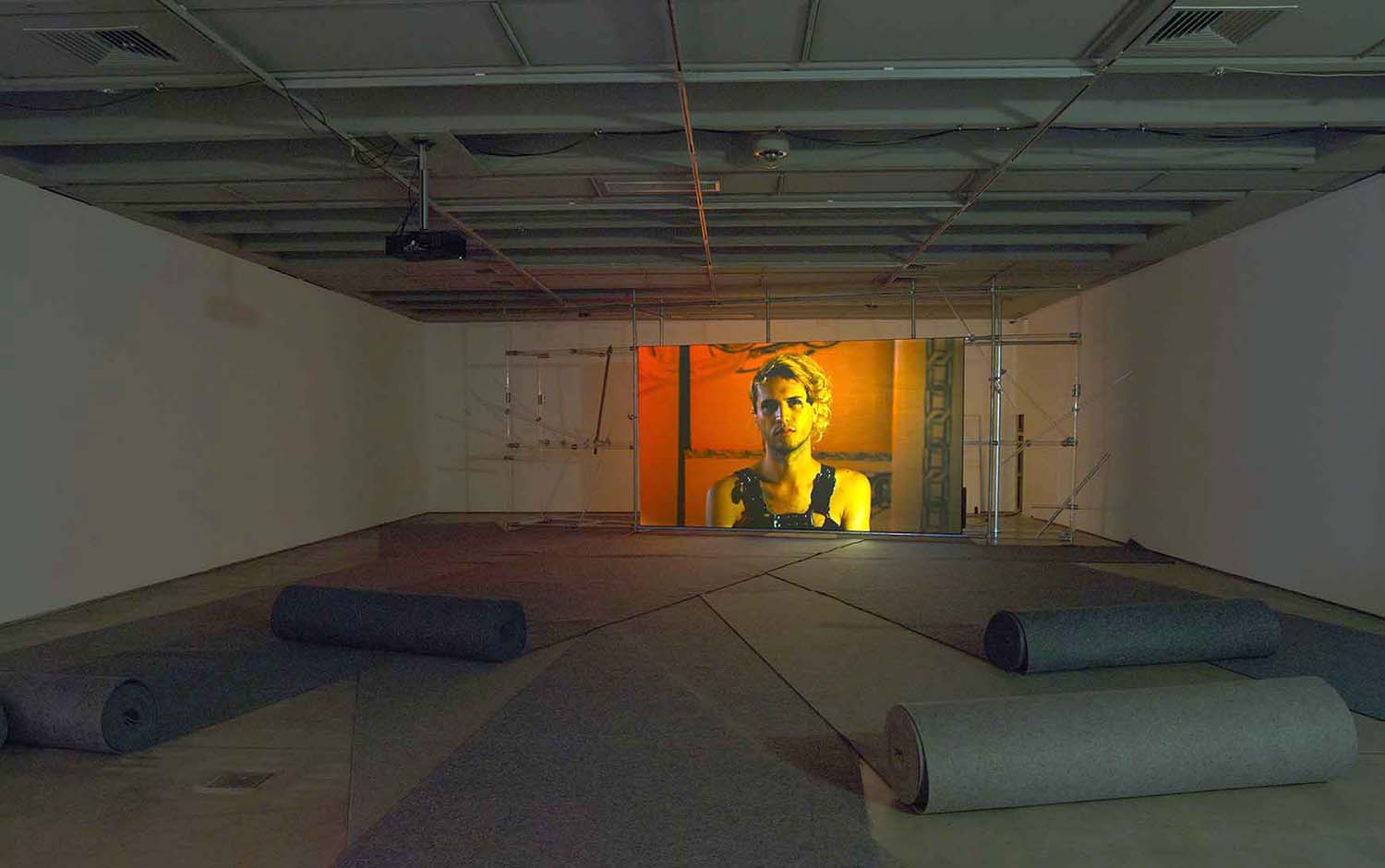

And then in the second exhibition space is a new video work that is about fourteen minutes in length, but it loops. For the first half it depicts different forms of industrial farming, reproductive farming in particular, but also the farming of skins, meats, furs, piss, milk, urine, semen. A whole range of liquid and flesh and meat rendered commodity.

The footage lapses between the state-sanctioned and the illegal, the very clinical forms that this takes and then the illegitimate. So, people skinning animals alive by hand in a marketplace versus the conditions of a factory or another type of industrial farming. And it’s rendered quite ecstatically or psychedelically.

The second half of the video is a text poem that appears on-screen, which describes the idea of life on Venus. Venus is a sibling planet to the Earth. It is the closest planet in terms of size and mass. But it is surrounded by these sulfuric clouds, these clouds of acid, and it’s constantly raining, but it’s so hot and the pressure is so great that the rain never even reaches the surface; it burns off in the atmosphere. There is a huge amount of pressure on Venus. I think there has only been one example of a probe that has landed on Venus and successfully sent images back, and you can almost see in the pictures this crushing heat. I was interested in using Venus as a way to articulate a parallel state of being — a parallel state of near life or near death, a place much like the one that we know, and I use that super broadly, a body, a space, a feeling of atmosphere or ecology that is familiar to ours yet totally permeated with a violence somehow. And in a way I realize as I describe the work that I’m expressing just a feeling of being queer or trans in the UK now — a feeling of being an other in an institutional space, and maybe also trying to work out some of the complicated feelings of exhibiting in an institution such as the Serpentine, but also dealing with these entanglements and interdependencies between what is living and what is dead, what is suspended in a state of being or of nonbeing.

QA: What drove you to make this show? And what did making it feel like?

PS: It is a really hard show to talk about. It’s something really intense that I had to make really quickly, and it’s something that I’m maybe still reckoning with in a way. Often I’ve worked quite slowly, and I think often very deliberately, even if it is a deliberate sense of the intangible, or of the hard-to-grasp or hard-to-hold-on-to.

I was talking to a friend yesterday and we were saying that both of us like to work with a certain amount of space and slowness; and this project, “On Venus,” has been made hard and fast, and I think that there is just a gut feeling of articulating some sort of pain, or like a quick response to an experience of violence that feels really present being in the UK. Sometimes you make work and it’s not until a lot later that you are able to understand what was happening. It sounds really trite to say that, but sometimes these things just have to land before you really realize what was going on at the core of your doing or thinking. But I knew from the onset that I wanted to somehow articulate these registers of harm that are imbedded in institutional logic, in institutional conditions, to try to not be dealing with the over there, the elsewhere. Maybe this comes from the last big work I made, called “The Prince of Homburg,” which used a play from the 1800s to try to express something about now, to think about being amidst crumbling empires, people losing their grip on power, and what that means and what happens in that moment. I guess after that I was like, no more dealing with something so far away, even if it is being used to say something about the present. This work feels immediate in a way, like I had no other choice but to make something that was immediate or felt responsive to a pressure that is surrounding us now.

QA: I wanted to ask about how this work relates to “The Foundation” in terms of reproducing an institutional structure, or maybe dislocating one?

PS: “The Foundation” was the product of a particular set of circumstances. Prior to that I was making work about communes or collectives, or moments of collectivity amongst people generally in Western Europe in the twentieth century, moments of sociality or communality that flourished in resistance to capitalism, industrialization, or Fordism or whatever. And it was 2012, and a friend of mine sort of sent me to the Tom of Finland Foundation in LA. She was like, “Oh, you should really go visit this archive. It’s really interesting and I think you might really like it.” And I went with maybe a little bit of an inquisitive and touristic spirit — you know, I was essentially here on holiday. And without necessarily being a huge fan of Tom of Finland the artist, but I was intrigued about visiting an archive of erotic art. I really honestly went expecting it to be a concrete modernist building that was air conditioned, where the archivist would welcome me at the door and ask what materials I was there to see, and there would be rules about photocopying works or taking pictures on your phone, you know, any of those normal trappings of an archive. But in this instance it’s a three-story house in Echo Park on a regular street, that was bought in the ’70s by five or so guys who essentially ran it as a commune. Tom started living there in the ’80s and ’90s, and the snake started to eat its own tail in a way. Tom started to make drawings of the men in that community, and the men in that community started to model their image after Tom’s drawings. Meanwhile the house started to become an archive of Tom’s work. Certain rooms in the house would get adapted to being archive rooms, bedrooms converted to file storage or whatever. Throughout that, though, people continued to live there; it still functioned as a hangout or congregational spot, it still had a sex dungeon and a pleasure garden. And when I went there and had the tour, I was shown the kitchen with as much reverence and importance as I was shown the archive. The row of shoes by the front door felt as valuable as these archives, and that was really compelling to me. I was really struck by it. And something that was happening simultaneously was me trying to figure out my transition — trying to figure out if I was about to start medically transitioning. While this dialogue was happening internally, I was being welcomed into this community of really predominantly cis gay men, and I felt welcomed into that context by virtue of their understanding of me as a cis gay man. In my head I was like, I don’t know if I am who you think I am, but if I articulate or actuate who I am will the relationship be irreparably broken? Will my access to this space be revoked, if not just damaged? Which was maybe a question I was also grappling with in my personal life in some way.

Luckily what happened was that I ended up being able to spend a number of years working in the Foundation with the people there, on this large project, which was dealing with these questions of inheritance and one’s presence in an institution, and really trying to understand how your identity might change the very making of a space for good and for bad in a way. In my work, at its core, I’m thinking about what is a good body and what is a bad body. What is valued and what is disposable? What is considered sick and what is considered healthy? And there is a large degree of ambivalence about the assumed or inherent worth of those dichotomies. In “On Venus” I am not arguing for the right to live. I’m not arguing for my god-given right to self-actualize. I think with “The Foundation,” and even more prominently with the works that came after it, there’s this question of what it means or what it takes to survive on your own terms, but with a deep suspicion about contemporary ideas of agency, particularly as they relate to identity or formations of identity or community. What was interesting to me at the Tom of Finland Foundation was this knife edge between a bid for something utopian and the inherent conservatism that comes with that — the moment or the question of what happens when you have to kind of close the doors to preserve a moment or a community, how you might have to draw a line of who is and who isn’t allowed in the room. That problem is always a specter in the work that I am making as much as it is always a specter in my own life, mostly rooted in being a gender-queer trans person; there is always that churning feeling. And I am ambivalent about trying to work toward some kind of wholeness or harmony.