This conversation revolves around The Company, Huma Bhaba’s (Karachi, 1962, live and works in U.S.) first exhibition at Gagosian gallery in Rome, that included new sculptures carved in styrofoam and cork, made of reused materials and raw clay, and cast in bronze and drawings on paper. The sculptures are arranged in form of a procession, and are partially inspired by The lottery of Babilon, a novel by J. L. Borges. Literature is typically a trigger of the artist’s work, who often evokes a narrative through the titles of works and by framing them in a specific display. There is a sense of monumentality in the exhibition, a tension between works and space that reverberates across the sculptures and the drawings. Like goddesses, or totems, the figures that populate the gallery are definitively presences.

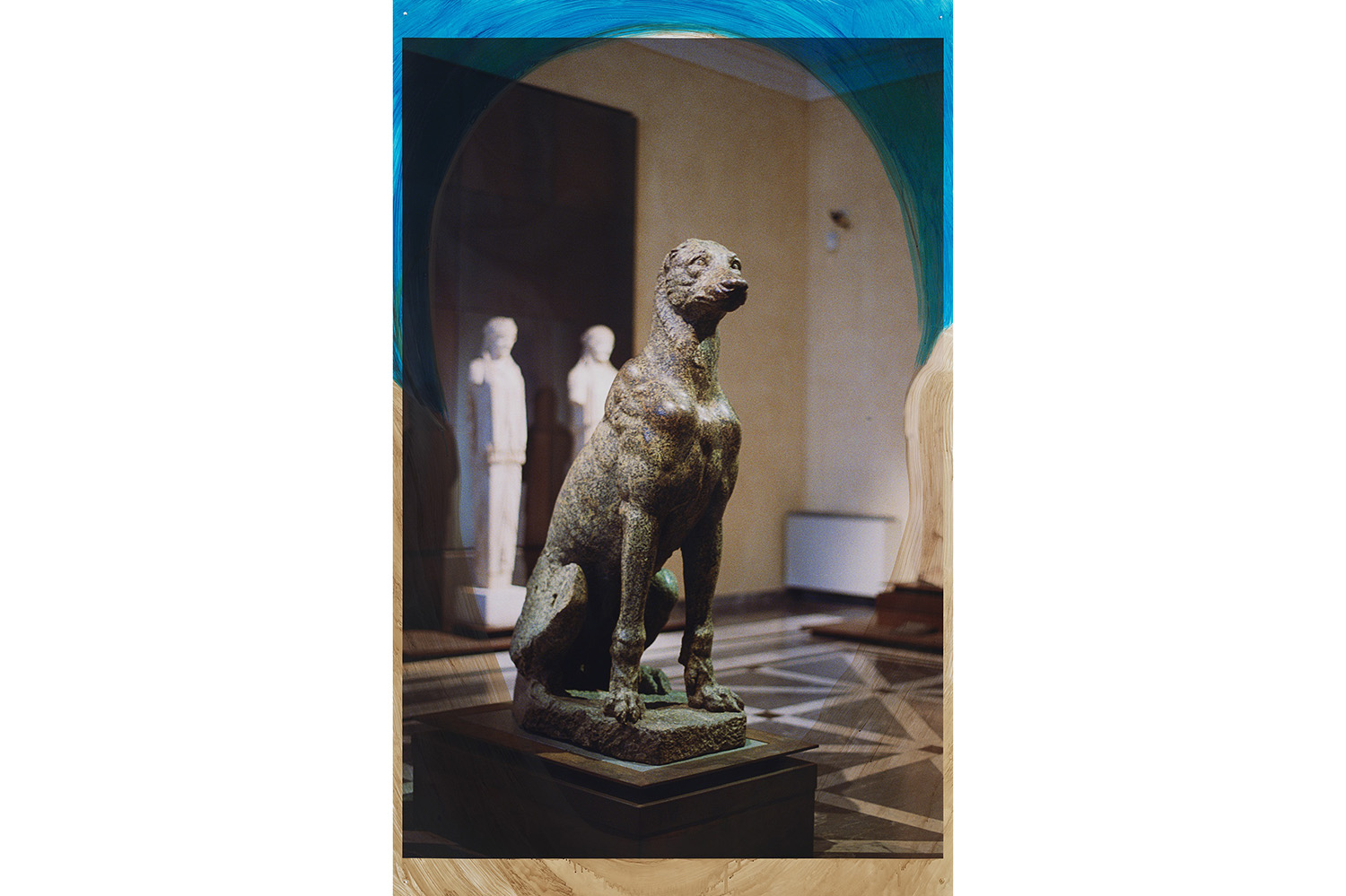

CECILIA CANZIANI: “I like dogs,” you said when we met in Rome, on a late September morning, during the press preview of your exhibition at Gagosian. I was looking at a large photograph of a granite roman sculpture representing a dog that you shot at the Musei Capitolini years ago, during a visit to Rome. The photograph was painted over but the dog was still discernable, framed in a blue oval — a head. Among the works on paper that you presented for the exhibition, this is the only one in which the background image appears so clearly, or in which the paint, that you normally apply in layers, over time, meditatively, leaves so much space for it. In your paper works — always based on photographs that you take and collect — the apparent erasure of the original subject isolates and therefore highlights a detail and at the same time builds onto the existing subject another image: often a face or a figure, in negative. More than with painting, these works seem to deal with sculpture: carving out a detail, modeling a form. I sense that it is connected to your sculptural works, where color highlights a part of the statue and overwrites the carved form.

HUMA BHABHA: I should have said I love dogs. The head in that drawing is dreaming what is inside it. I have been making works on paper and photographs for some time, but when I started working on them side by side I realized how they were an extension of my sculpture. Also there is a history of sculptors that I admire who also produce amazing drawings (Bourgeois, Beuys, Smithson, etc.) and I am inspired by that.

CC: The dog that you photographed had a hard, crystalline quality and a self-enclosed shape. It is a presence, and it seemed to relate very strongly to the procession taking place in the main room of the gallery, and to connect them to the solitary figure positioned at the entrance. It made me think of the dog at the foot of the funeral monument for Ilaria del Carretto, by Jacopo della Quercia, in the Cathedral of Lucca, and of the two striking dogs depicted in the Piero della Francesca painting of Sigismondo Malatesta in Rimini: they are symbols of fidelity and watchfulness, and yet they are real presences in the work. I guess one of the reasons I keep thinking of them in relation to your work is because they share a similar quality to your standing sculptures: Receiver (2019) watches over the entrance. You feel the sculpture’s volume, weight, and character as you pass by it. The sculptures in the oval room, presented as a procession, function similarly: one sculpture after another, in line with the long vertical of the room. A sense of “being there,” of “presence” is very strong in these works, and is connected with the way they are positioned in space and in relation to the viewer.

HB: I was very aware of the shape of the room when I first visited the space in 2010; nine years later, when I was thinking about my installation, I knew the only way I could dominate the space was by arranging the sculptures in a procession. But the idea of a procession, or a caravan as I thought of it, created a strong narrative as to who these figures were, how the giant hands with the invisible body were dragging and clearing the way for the rest of the company.

CC: You always play with different sources — Egyptian art, Gandhara sculpture, modernist sculpture but also pop culture, B movies, theatrical props. Yet in this exhibition the archaic character seems to be more evident. The statues are standing, walking, seating; they are full figures or busts: it is a collection of traditional representations of the human figure in sculpture.

HB: I have always been interested in learning from traditional forms of representational sculpture, but having the context of Rome for the work caused me to slightly lean more on the historical or ancient rather than the pop sci-fi direction.

CC: Your typical fragmentation and montage of different elements of earlier works is here disappearing in favor of a totemic presence. Prophet and Loss (2019) are sculptures — not fragments — of two hands. Each statue stands on a plinth that defines a space. And the plinths are all different: the height and the material is specific to each of them.

I have the feeling, however, that in terms of addressing a world in ruins and dystopian landscapes, your works also talk of a possible reconfiguration, at least when we analyze them from a formal point of view.

HB: I thought that by integrating the idea of different pedestals and museum displays with the implied narrative of the procession that the grouping would become more complicated. It’s a formal choice.

CC: Thinking of your work in relation to contemporary artists like Kader Attia or Thomas Houseago, there seems to be a common interest in a notion of monumentality that is de-ideologized by the use of impermanent, common, degraded materials, and in referencing modernism as a way to undermine its cultural (Western, colonial) premises. And yet, in “The Company” I feel very clearly the presence of Picasso and Giacometti, both for their modernist reconfiguration of the archaic and the sculptural, and also for the research on the subject of generating a space. The position of the statues triggers the idea of a potential advancement in space.

HB: I agree completely. And sometimes it’s easy to view sculpture purely through the ideological fashion of the moment. Trying to think how Giacometti was thinking can be productive; he wasn’t a blockhead.

CC: The exhibition is divided into three stations, so to speak, that make use of the space by creating three different environments.

HB: Receiver is there to meet and greet. Then, as you move through the two-dimensional figures in landscapes (the drawing/snapshots of the world where these beings originated), you enter the larger landscape that allows for the mind to wander not only from sculpture to sculpture but to feel free to imagine what is behind this configuration of implied procession or movement.