The venue of the second edition of the Lagos Biennial is an abandoned twenty-five-story office building in which windows are broken, some rooms have no windows, conduits for heating or cooling hang from the ceiling, and electrical wiring is exposed. There is colorful graffiti and creeping moss on the walls, and the floors are strewn with broken bricks and bamboo. Outside light cannot penetrate some areas, and one cannot go beyond the fourth floor because huge slabs of wood barricade the staircases.

The building has been abandoned for nearly thirty years. Choosing it as the site of the latest edition of the Biennial was, frankly, genius.

Themed “How To Build a Lagoon with Just a Bottle of Wine,” and curated by Antawan I. Byrd, Tosin Oshinowo, and Oyinda Fakeye, the Biennial sought to grapple with one of the most urgent topics in the world today: the accelerated urbanization of cities. In Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, the consequences have been dire for its inhabitants and the body and sustainability of the city itself.

The venue of the Biennial itself shows the diagnosis is not good. The building in question was a “gift” to Nigeria on the occasion of her independence from her benevolent colonizer, Great Britain, in 1960. The building has since lived several lives, home to businesses and the state. Then it suffered a fire. Then it was left to rot. Other new, “ultra-modern” (a favorite term of politicians) buildings have since sprung up to replace it. In Lagos and Nigeria at large, the “ultra-modern” is far more prized than the preserved or renovated. In keeping with the state’s aspiration to become a twenty-first-century ultra-modern “mega city,” it spends considerable energy building the new — and not sparing anything in the way. The city is currently crumbling under the weight of this rapacious taste for shiny development, which does not serve people but rather the egos of those they elected.

The Biennial’s participating artists and curators, in reflecting on this state of affairs, clearly understood what was at stake. Even the Biennial’s title is a call for the miraculous. How, indeed, do you build a lagoon from a bottle of wine? How do you speak to issues that have stubbornly remained the same for years, with no signs of changing?

Some artists approached the theme through the everyday: how people navigate the city, how the city cares for its own, and its capacity for compassion — or lack of it.

In multimedia artist Karl Ohiri’s video Rolling Footage (2019), we see how a young man with no arms and legs moves around on a rollerblade-like machine he created for himself. He is representative of how the differently abled have to navigate between legs and cars (at face level with exhaust pipes) to traverse mere meters of space. There is no infrastructure built with them in mind. Not being able to walk on your own two legs is a heavy and often lonely burden in a city like Lagos.

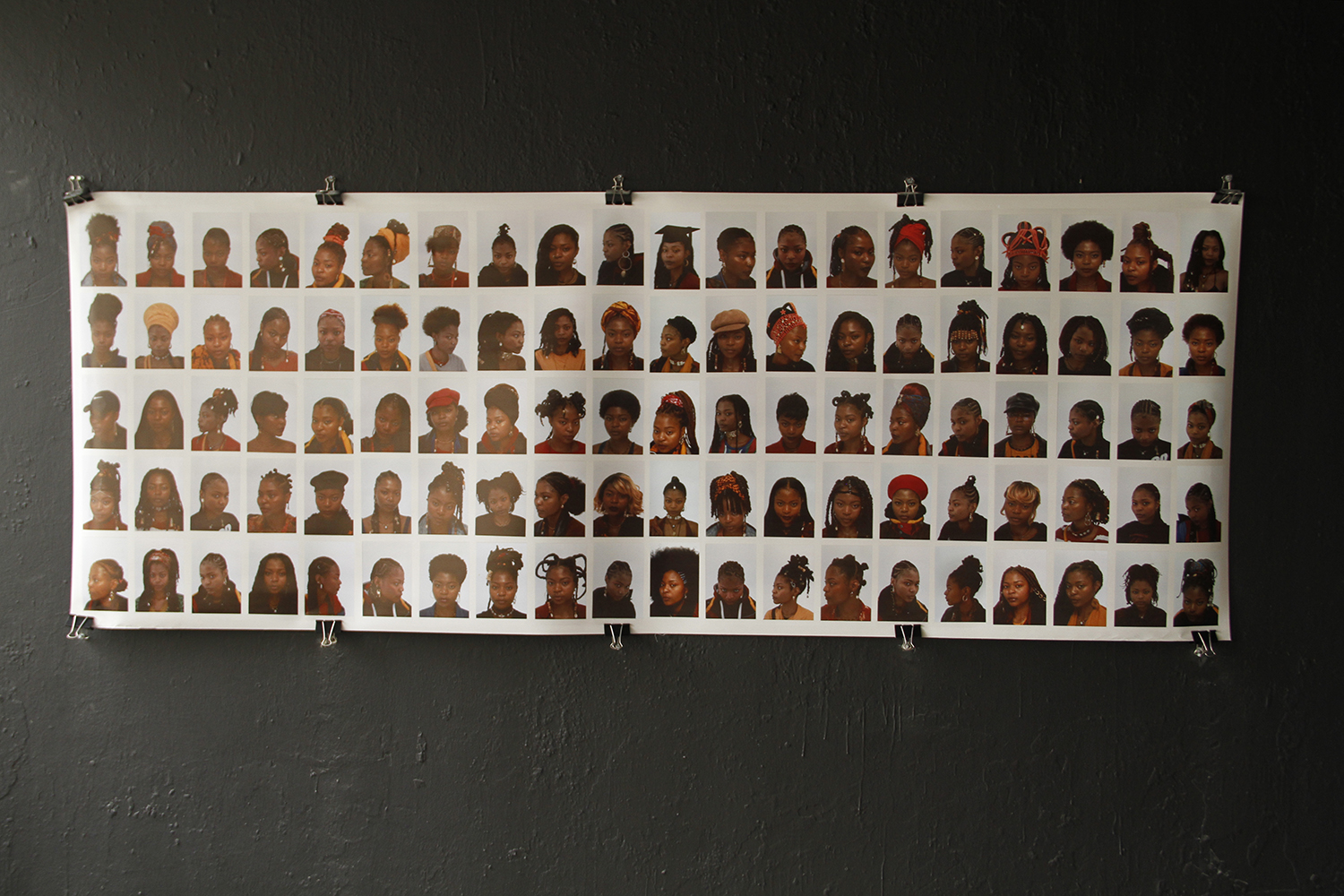

Sabelo Mlangeni’s mesmerizing monochrome photographic series “Royal House of Allure,” exhibited on a pink wall, portrays the city’s LGBTQIA youth, who have decided to create a space for themselves in a city that otherwise won’t have them. They laugh. They dance. They fellowship. They are also under attack. Just this month, forty-seven men went on trial for the first time under Nigeria’s anti-homosexuality laws. The men were arrested in a police raid on a hotel. The police claim they were being initiated into a gay club. The accused say they were only attending a party. Mlangeni’s decision to show the faces of his subjects is fascinating, and even potentially dangerous.

Nneka Ezemezue’s series “The Vendors” (2019) depicts groups of people — usually men — who crowd around newsstands to debate the politics of the day. To the average passerby these men may appear idle, but they often show a stunning, sophisticated awareness of the world around them. Looking at the photos, I wonder what they make of the fact that the more Lagos rapidly urbanizes, the faster it splits at the seams. In Uthman Wahaab’s breathtaking, large-scale charcoal-and-conté-on-paper work titled Back With Me Again (2019), we see the pursuit of selfhood — a woman insecure about her weight in a city where people are quick to ridicule, objectify, and sexualize her.

Some artists grapple with the city’s indifference to its own memories. Andres Lang’s photographs of state-sanctioned demolitions of historical buildings show a state committed to forgetting. We see how these demolitions are not only a failure of urban planning but also of the preservation of knowledge and history. They do not happen because there is no space to build the new; they happen because there’s no appreciation for these instruments of memory — what they mean, what they represent.

The first floor of the Biennial has no walls on one side. Looking out on the rest of the city one sees sprawl: people, cars, buildings, all occupying spaces that seem insufficient. These inhabitants experience a kind of scarcity that the city itself enables — a city whose “progress” benefits only a few and punishes many. It is a city bent on imploding, its eager hands on the detonator. The Biennial contemplates a miracle. But it is not coming.