Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Thinker. Artist. Innovator. These are just three words that could be used to describe Rudolph Laban, the German pioneer who was fundamental in the rise of modern dance in Central Europe. Initially having trained as an architect — a schooling that influenced his approach to movement and space — he is arguably best known for creating his eponymous notation system, “Labanotion,” in 1928, which recorded movement and choreographic phrases by way of intricate symbols. However, Laban was also a prolific choreographer of works for the stage. Aside from a few photographs and textual fragments, little evidence — and absolutely no film footage — remains of these early-twentieth-century works, meaning that Laban’s choreography has remained lost to generations of artists and audiences. That is, until recently.

Choreographer, dance artist, and academic Alison Curtis-Jones — who is a lecturer at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London — has made it her mission to give Laban’s lost works a new lease on life in the twenty-first century. She first encountered his work when she herself was a student at Trinity Laban in the 1980s, during which time renowned researcher Valerie Preston Dunlop — who trained directly under Rudolf Laban himself at his Art of Movement Studio in Manchester — was putting together a draft reworking of Laban’s 1926–28 piece Green Clowns, an anti-industrialist work that addressed the fear many artists in Weimar Germany had of burgeoning technologies. But it wasn’t until Curtis-Jones returned to Trinity Laban to do her master’s degree that she became committed to researching this area herself. “It intrigued me. I thought that it was really interesting to look back to the past, and I asked myself how I could use these works to appeal to contemporary audiences.”

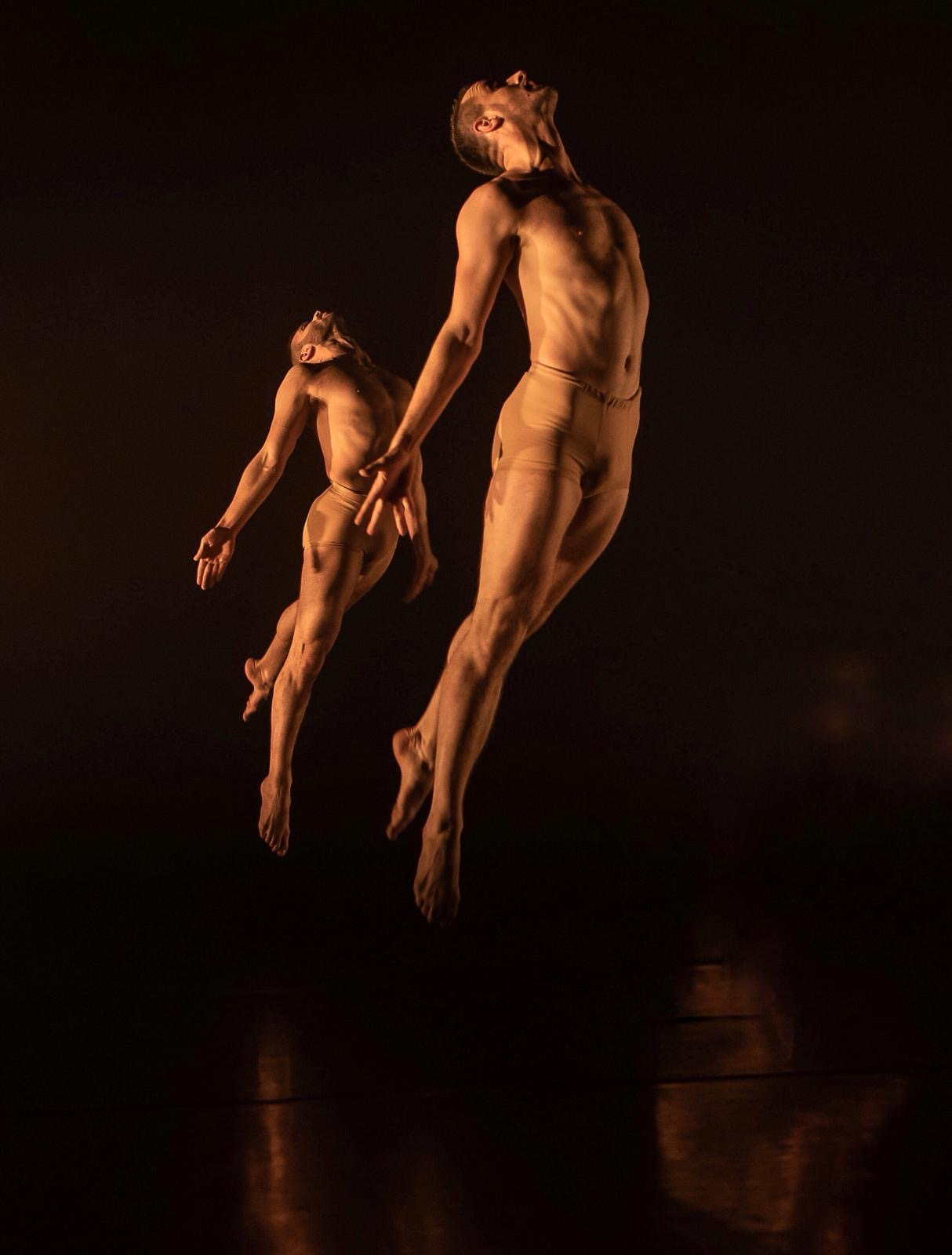

First mounting her own full-length version of Green Clowns in 2008 — developing some of the ideas Preston-Dunlop had already put in place — Curtis-Jones has gone on to devise new versions of a wide variety of Laban’s works, moving away from what Preston-Dunlop was calling a “re-creation” and now pursuing her own “reimaginings.” “I’ve developed my own methodology using choreutics and eukinetics” — theories Laban developed in 1947 and 1966 to explore movement’s relationship to space and dynamic expression — “and I use those principles to look back retrospectively at works from 1913 and 1927,” explains Curtis-Jones. Over the years, her reimaginings have been performed both by Trinity Laban students and her professional company Summit Dance Theatre, the most recent restaging being at the Laban Theatre in London in November 2019. This double bill saw the restaging of Nacht and Drumstick — originally titled Die Nacht (1927) — and The Dancing Drumstick (1913), which Curtis-Jones first reimagined in 2010 and 2015 respectively. Whereas Nacht is a political satire that sees decadently dressed dancers explore the glitter and doom of Weimar Republic culture, Drumstick is a more abstract consideration of the relationship between movement and music. “Drumstick really goes back to the body in its primal form,” says Curtis-Jones, describing how her reimagining of the piece sees a group of performers in tight nude underwear embody complex rhythmic phrases to the sound of a lone drummer. “It’s the dance that drives the music.”

It’s difficult to imagine how Curtis-Jones goes about creating her interpretations of works from more than one hundred years ago without any record of the steps. But, apparently, being faithful to the original choreography is not the aim. “For me, it’s not about exhuming a relic, and it’s not about trying to make the work as it was,” she says definitively. “It’s about gathering as much material remains and evidence as possible to then make these works with contemporary practitioners for contemporary audiences.” Seeing the limited material remains of the choreography as potential evidence, Curtis-Jones works with the idea of “filling archival gaps. Then, just like any archive, it’s about how you interpret what you see.” While this task may be daunting to some, Curtis-Jones sees the limited evidence as giving her a greater opportunity for investigation and creativity. “But it’s also not about deviating so far from the original sources. It’s about how I can use them in a way that pays tribute to the ideas behind them.”

For her reimagining of Drumstick, for example, Curtis-Jones spent two years researching before even stepping foot in a dance studio. Traveling to archives around Europe, including Kunsthaus Zürich, she read letters Laban had been writing in 1913 in order to understand what his primary interests were at the time of creating the piece. “He talks about how he wants to free dance from the constraints of music, so this inspired me to physically research how I could work with the body in a rhythmic way that didn’t rely on sound,” says Curtis-Jones. While this method of working isn’t unusual today — “musicians following dancers is something we do a lot in contemporary practice” — it was revolutionary within the context of the early twentieth century. “[I’m] proposing that Drumstick is a quite a significant historic work, because it is the first time that the power relationship between music and dance changed.”

Curtis-Jones has an expanded definition of the term archive, as she also sees the dancers she works with as “living archives,” retaining choreography in their bodies so they are able to recall it for various restagings. While to some, relying on performers’ memories to keep a work alive may seem like a risky practice, Curtis-Jones believes that we should accord more value to dancers as documentary evidence. “It’s interesting, because Laban created his notation system in 1928 as a way of trying to raise the profile of dance to that of music. But then he didn’t really use it to record a lot of his choreography. He really moved away from [this system] because it didn’t adequately reflect the dynamics of movement. That’s why he went on to devise effort theory” — the study of dynamics in movement — “in 1947,” she explains. “People tend to think of archive documents as tangible paper trails, but actually the oral history and experience of doing is in dancers’ bodies.”

As well as researching Laban’s works and theories themselves, Curtis-Jones also looked closely at practitioners from other art forms to help her form a distinct impression of the works’ contexts. This was particularly important for her reimagining of Nacht, which, as a political satire commenting on the state of 1920s Berlin, required an in-depth knowledge of the culture of the Weimar Republic. “I looked at the work of German artist George Grosz and Arbeiter (Workers) in particular,” she says, referring to the 1921 drawing depicting hunchbacked Berliners solemnly making their way to work. “I was struck by it because so much of the history of 1920s Berlin is concerned with a veneer of beautiful fashion, but actually the culture was toxic, it was in crisis. I wanted to be able to portray both of those things.” Fritz Lang’s cult movie classic Metropolis (1927) portrays repressed workers, and its concern with the relationship between men and machines was also very informative. “Because how can you portray an era that you’ve never been part of? You can only glean it from what you can gather, and then ultimately it’s about your interpretation.”

While the Weimar Republic was founded one hundred years ago, in 1919, Curtis-Jones believes that the Nacht’s criticisms of the time are still relevant to modern audiences. “It’s so interesting to see what’s happening in our culture today compared to what happened then [in 1920s Germany]” she says. And she’s right: when presented with a work that discusses the era’s issues with hyperinflation, political propaganda, and false appearances disguising deeper issues, it’s hard not to equate them with contemporary financial banking crises, fake news, and unattainable facades assumed on social media. The overarching mood of the Weimar Republic was one of paradox — with glamorous film stars, parties, fashion, and jazz music coexisting alongside wounded war veterans and hungry workers queueing for loaves of bread. Nacht captures this spirit, starting off with the dancers debaucherously reveling to the sound before descending into marching motifs alluding to the rise of Nazism. Because of the hardships of postwar Germany, “people wanted something to believe in,” says Curtis-Jones. It’s a chilling statement that is all too equatable with the motivations behind the largely rightward shift affecting Europe and beyond today.

Yet what is the value in looking back to the past in an art form that often views originality as a criterion for quality? According to Curtis-Jones, history seems in general to have become a “dirty word” in contemporary dance practice. “In today’s society, in this race to invent, create, and to move forward, particularly in the technological world we’re in, it’s always about what’s new. I feel the same thing has become a trend in choreography,” she says, mentioning that she recently wrote about this topic for a chapter in the Routledge Companion to Dance Studies. “We’re saturated with so much work. People throw stuff away and move onto the next thing. This notion of crafting, when you return to something and keep working on it, has become a lost tradition somehow.” Noting that contemporary dance history is short in comparison to other art forms — the beginning of the twentieth century is widely regarded as when the genre was born — she becomes even more incredulous at the industry’s reluctance to acknowledge its past. “You wouldn’t dream of going to drama school without looking at Shakespeare. So why are we not so concerned with our history in contemporary dance practice? Everything has evolved from something else,” she says, referring to how modern-day release technique — a method of movement that encourages the use of gravity and momentum to facilitate efficient movement — came about as a rebellion against the work of dance pioneers Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, who in turn had developed their schools of movement to break away from classical ballet. “If you don’t know your own lineage, how can you be an informed practitioner?”

In his biography, Mark Twain said, “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible. We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations. We keep on turning and making new combinations indefinitely; but they are the same old pieces of colored glass that have been in use through all the ages.” It’s a quote that seems to fit perfectly with Curtis-Jones’s practice, and one that makes her smile when she is presented with it. “That’s a lovely image actually,” she says contemplatively. “So you create new forms from evidence that already exists. That’s exactly what I do when I reimagine Laban’s works.”