Entering the gallery I encounter a huge canvas, so large that it occupies an entire wall — tall enough to envelop the viewer. This is Zhao Zhao’s Constellations (2019), one of several works presented at Mizuma Gallery, Singapore. In “Control,” his first solo exhibition in Southeast Asia, the Chinese artist explores what it is like to achieve the freedom and independence that is enjoyed by many artists in the West. Like others, Zhao feels that decades of ideological restriction have controlled the minds and visions of both artists and their audiences, leaving them despondent, anxious, and frustrated.

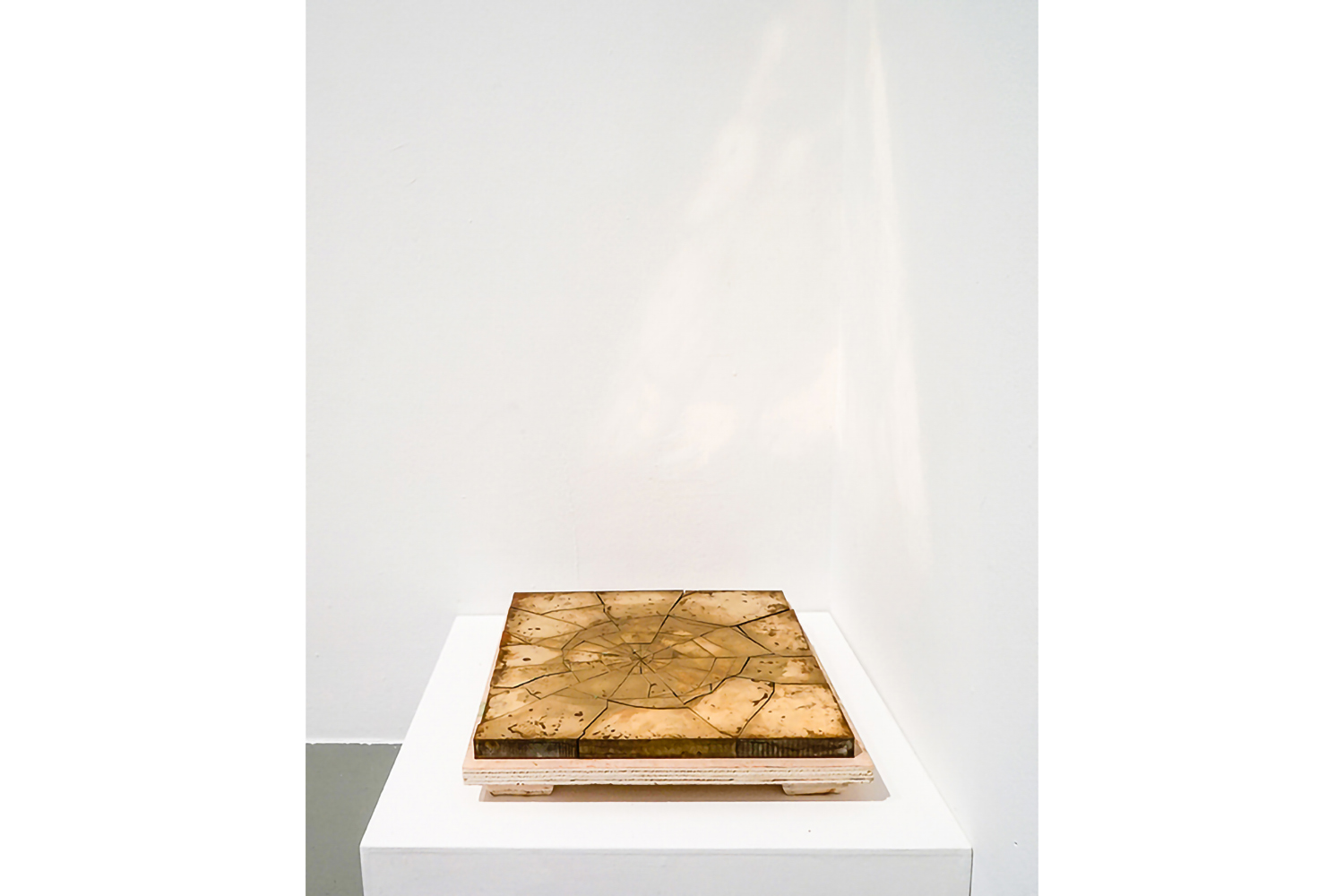

In Constellations (2019), form, as opposed to color, structures this huge work; the precise lines and shapes create a dynamic balance that pulses throughout the canvas. Reproduced by hand in embroidery on silk, Zhao’s fragmented and fractured forms are awash in navy blue space, appearing to be caught in arrested motion, a still frame of drama and mysticism. The expressive, abstract forms depicted engage me in an active aesthetic experience.

In fact, the work can be traced back to a sensory “event” — a road accident in 2007 in which Zhao’s head was smashed against the windshield of the car he was traveling in. The shards and chunks of broken glass so inspired Zhao that the result was the “Constellation” series. The giant spiderweb-like patterns, somber colors, and perilous structure in this work reflect the psychic and social state of China since Mao’s death in 1976.

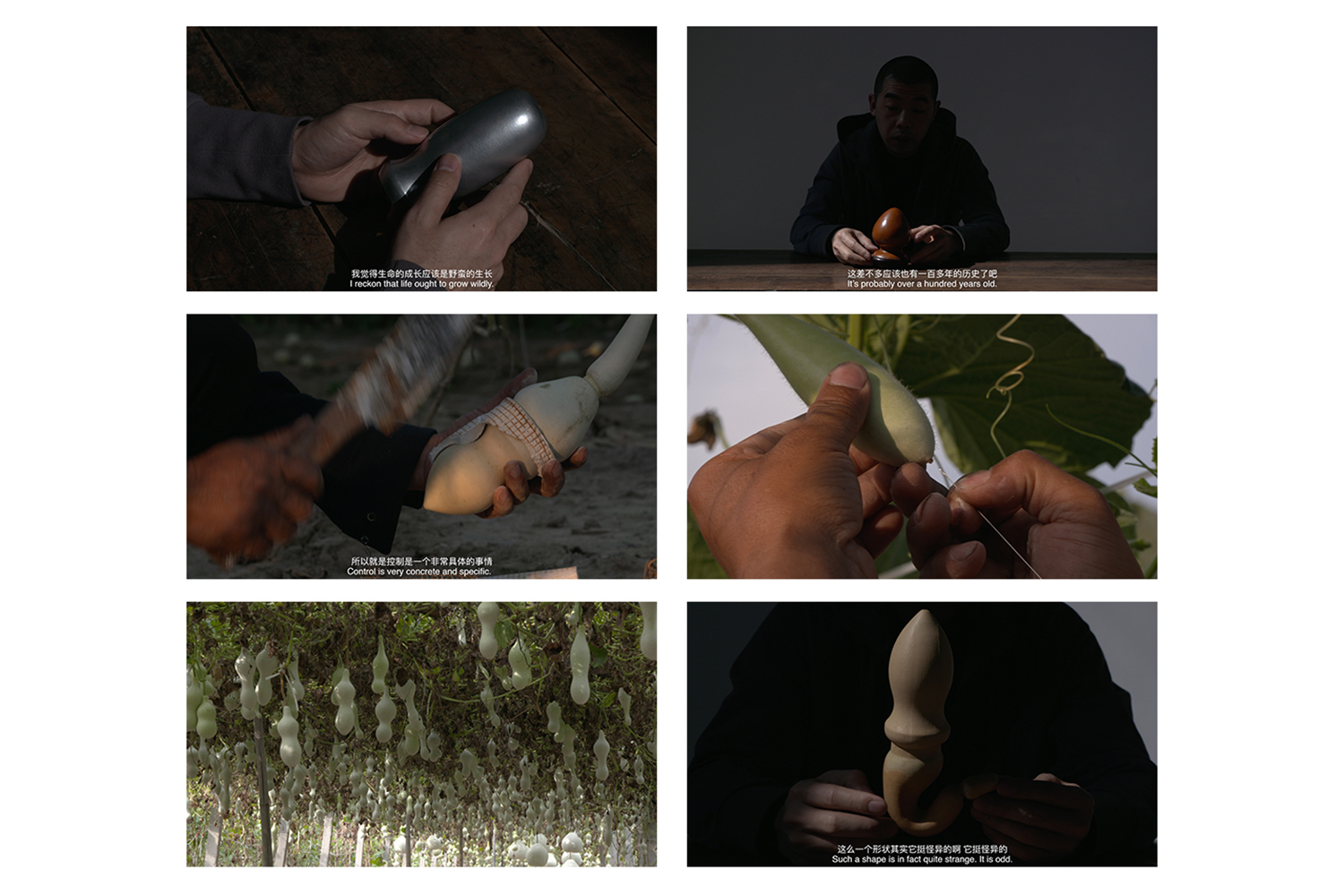

Another work notable for its sheer size is Zhao’s Control (2019). Here the bottle gourd is used as a metaphor for the manipulated subject; the large sculpture, displayed prominently in the room, expresses the natural growth processes of a plant while at the same time contorting its shape. In 2015, Zhao even purchased a plot of land in Shandong and started growing bottle gourds in order to closely observe their characteristics. Thus, the “Control” series encompasses the artist’s painstaking labor, in which flowing, organic bottle gourd forms are rendered in different materials such as stone, steel, and marble.

One towering bottle gourd is made of stainless steel. A gleaming, stylish household metal, Zhao’s material functions as a distorted mirror reflecting the viewer. In this way the work slyly hints at Chinese power subjecting the minutiae of individual lives to an authoritative gaze. Additionally, the sculpture is set atop a customized rosewood stand made using traditional mortise-tenon joinery techniques, as widely found in ancient Chinese buildings and furniture.

The juxtaposition of traditional craftsmanship and industrial mass production is evident. Even the humble bottle gourd — a symbol for longevity and good fortune — suggests a cultural practice of the past that remains vital in the present. Thus “modern” and “traditional” are not in opposition. The underlying rationale is that tradition is not culture that is left behind in the transition to modernity, but rather that tradition is what modernity requires to prevent society from falling apart. This invisible current is woven throughout the exhibition. Zhao invites us to engage the values of the past despite current political and social circumstances. For him, and us, it offers a way forward.