“A community for all the arts … a cultural center for the new age.” This sounds like another Bauhaus centennial celebration, currently ubiquitous in Germany. But it is the closing promise for the planned CalArts school in Los Angeles, as stated in the Disney-produced short film The CalArts Story, produced as part of a fundraising effort in 1964. Apparently successful, it took only another six years until the school was able to move onto its new campus, by then having merged with the Chouinard Art Institute, which had been educating draftsmen for Disney productions since the late twenties, and the traditional Los Angeles Conservatory of Music.

The show’s two curators, Kestner Gesellschaft director Christine Végh and LA-based curator Philip Kaiser, started working on the exhibition four years ago, and filmed interviews with thirteen artists active at the school, among them Judy Chicago, Barbara Bloom, Suzanne Lacy, Matt Mullican, Klaus vom Bruch. These commentaries constitute a critical but also anecdotal storyline illuminating the exhibited works, many of which were produced in the early 1970s heyday of CalArts.

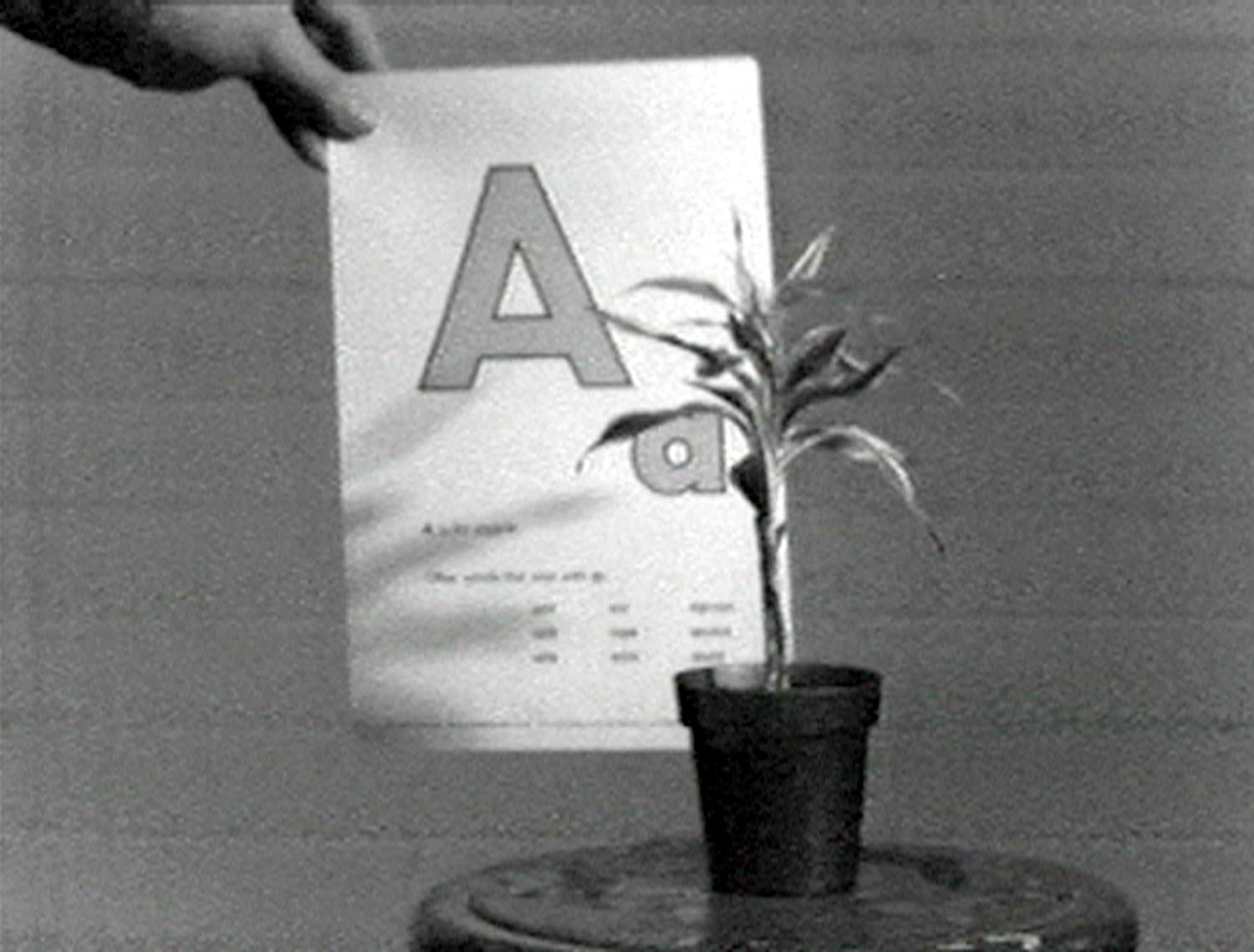

The historical exhibition shows that dialogue between two distinct areas of practice were key to the success of the budding institution. Generous funding and artistic freedom early on allowed the first school president, Robert W. Corrigan, to hire visionary artists, including internationally known Fluxus veterans such as Nam June Paik, Alison Knowles, and Allan Kaprow, alongside regional innovators such as John Baldessari and Michael Asher. Each coined their own innovative teaching programs, such as Asher’s “temporary structures” or Baldessari’s “post-studio” course. In an interview, post-studio alumnus Stephen Prina recalled being congratulated for not needing a studio anymore; rather, he learned that “the world is your studio.” Works in the show reflect the discourses of the period, such as John Baldessari’s video Teaching a Plant the Alphabet (1972), which shows the artist literally doing that, or Douglas Huebler’s Represented Above is the Shadow of a Point (1970). Both pieces deliver a somewhat humorous reflection on the difficulties of being a serious teacher in a transformative art-school setting.

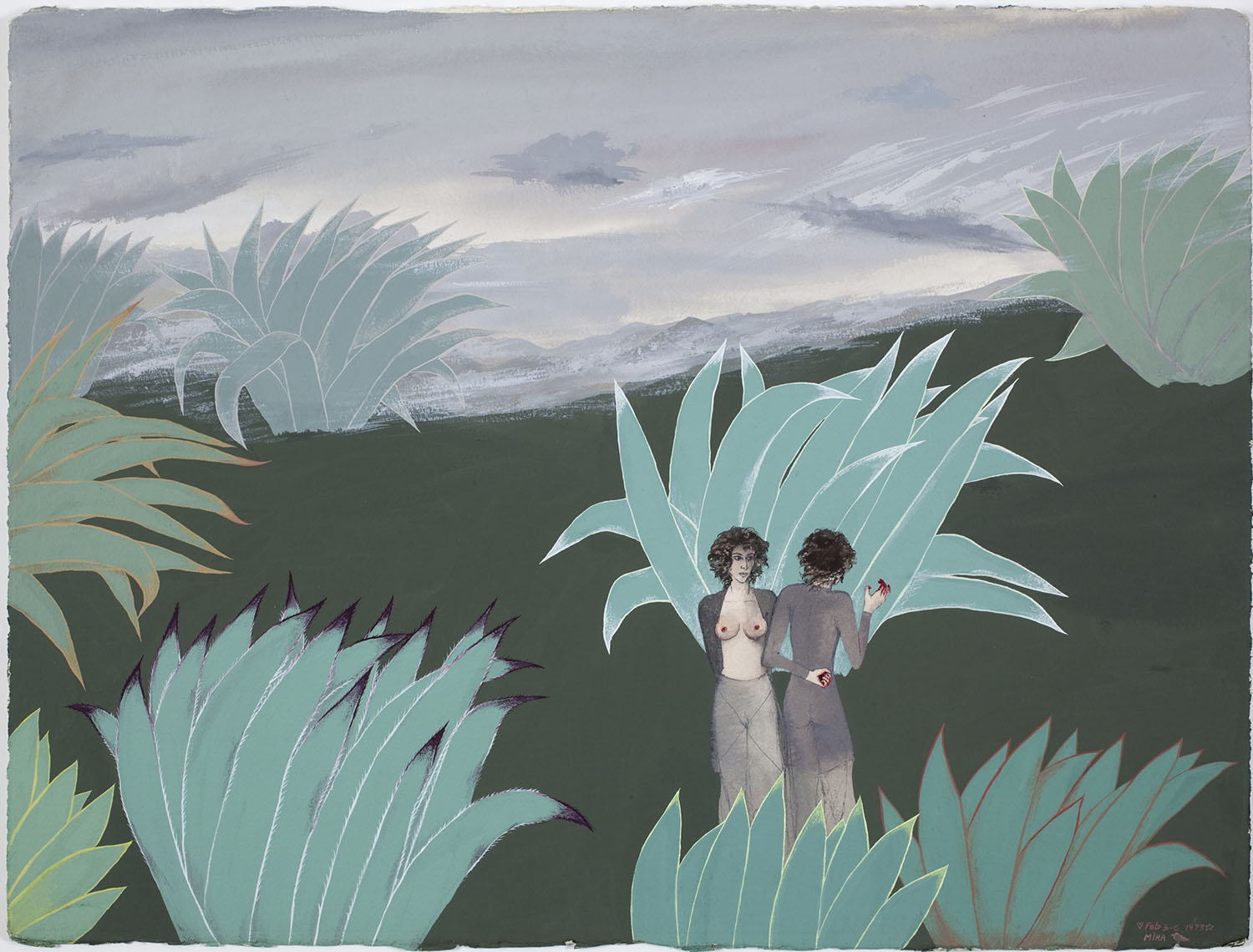

The counterpart to this idea-oriented emphasis was the short-lived but equally influential Feminist Art Program (FAP), established by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro. Recruiting only female students, among them Suzanne Lacy and Mira Schor, they sought to develop concepts around women’s art history, art practice, and general “consciousness raising.” The FAP’s activities peaked with the Womanhouse exhibition project in 1972, a surprise success that drew thousands of visitors. The outspokenly feminist site-specific installation and performance program was set up and run entirely by female artists in a run-down mansion in Hollywood. Works included installations such as Crocheted Environment by Faith Wilding and Menstruation Bathroom by Chicago, and performances such as Wilding and Chicago’s hilarious Cock-Cunt Play.

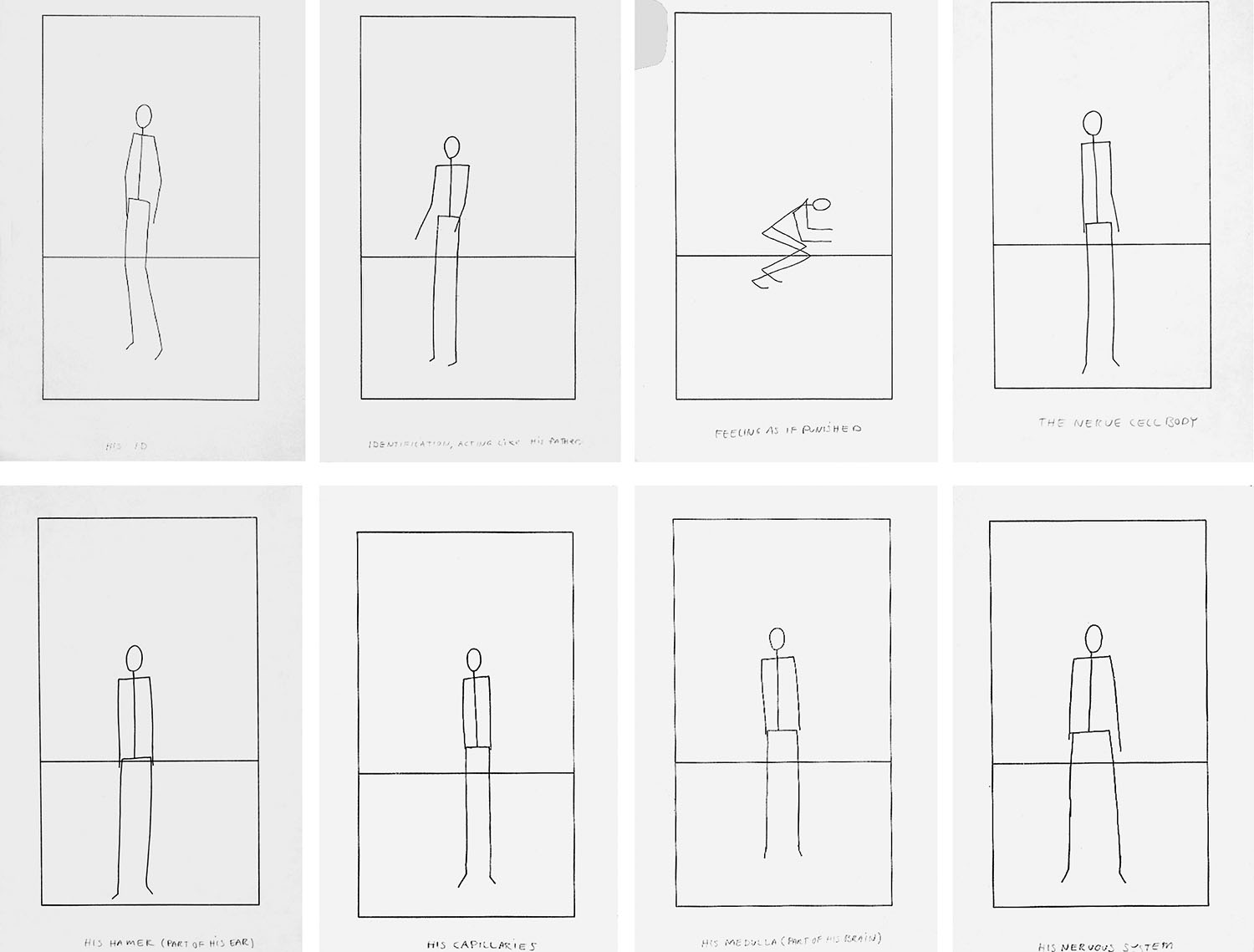

Artistic positions of later CalArts students show a fusion of these earlier discourses — a synthesis of the formalist and sociological aspects of the post-studio conceptual approach and the systematic critique of inequality and gender roles pursued by the FAP. This sometimes resulted in a politicized focus on psychological, spiritual, and occult imagery and narratives, prevalent in the works of Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw, Mike Kelley, or Ericka Beckman. Or in the beautifully direct and refreshingly empathic photo series “Family Pictures and Stories” (1982) by Carrie Mae Weems, which explored aspects of the artist’s everyday family life. The latter being one of the only works in the exhibition by a person of color suggests that the early years of Cal Arts is also a story of white, middle-class privilege.

Personal disagreements lead to Chicago leaving the school, and, in spite of its success, the FAP was defunct by 1975. Already Disney family support had dwindled in tandem with the growing politicization of the school (and, as former students recall in interviews, naked performances and swimming-pool parties around campus that were famously unappreciated by visiting trustees). Much of the staff associated with Fluxus also stayed for only a year or two; since the mid-1970s Baldessari’s post-studio class has taken center stage. Still, over time, the school fulfilled its initial objective and contributed significantly to making LA a counterpoint to the New York art scene.

The show will travel to Kunsthaus Graz in Spring 2020.