Some things are over in no time at all, and some things linger, even if one would like them to go away. One example of the former could be that first gust of excitement brought by the Venice Biennale, which seems to vanish in a matter of two or three days. An example for the latter, as I was reminded upon returning home, is the continuing presence and potentially growing trans-European influence of apparently corrupt right-wing populists, exemplified by the scandal caused by a recently published video shot in Ibiza, showing two leaders of an Austrian far-right party offering nothing less than to sell out their country’s democracy.

Within Berlin’s multicultural hodgepodge of an art world, this story may seem distant. But it offers an incentive to look again at one of the most discussed group shows of the season, “Global National,” at Haus am Lützowplatz. Curated by critic and curator Raimar Stange, the exhibition aspires to ask questions, such as: Can art today be critical of and resistant to nationalism and racism? Can an artwork have social or political impact? But how to pull off a feat like that? The curator insists on finding accessible artistic positions. “Art should not be elitist; it must be there for all,” says Raimar Stange, presenting works of art that ostensibly represent “critical populism.” It sounds surprisingly simple, and harkens back to a history of artistic critical populism, by the likes of artists such as Martha Rosler — whose recent work is also included in the show. In all, twelve artists have been invited. While the established figures mostly provide historical reference, it may be the younger artists who find more striking responses. Of course, Romanian master draftsman Dan Perjovschi’s trademark wall drawings, of which only a few are in the exhibition, offer a first glimpse of the potential of cartoons that satirize the use of language. Berlin-based artist Christine Würmell has long been researching the ways resistance manifests itself in the public sphere, with a particular focus on graffiti, slogans, and paint bombs. Here she presents a stack of demonstration signs, leaning against a wall, with photographs of a paint-bombed ad campaign by the interior ministry, in which refugees were asked to return to their countries of origin. In a country formerly proud of its “welcome culture,” the question is whether this offering of protest signage is a sincere invitation to viewers to take to the streets, or if the installation rather reflects the public’s reluctance to take action or even utter opinions.

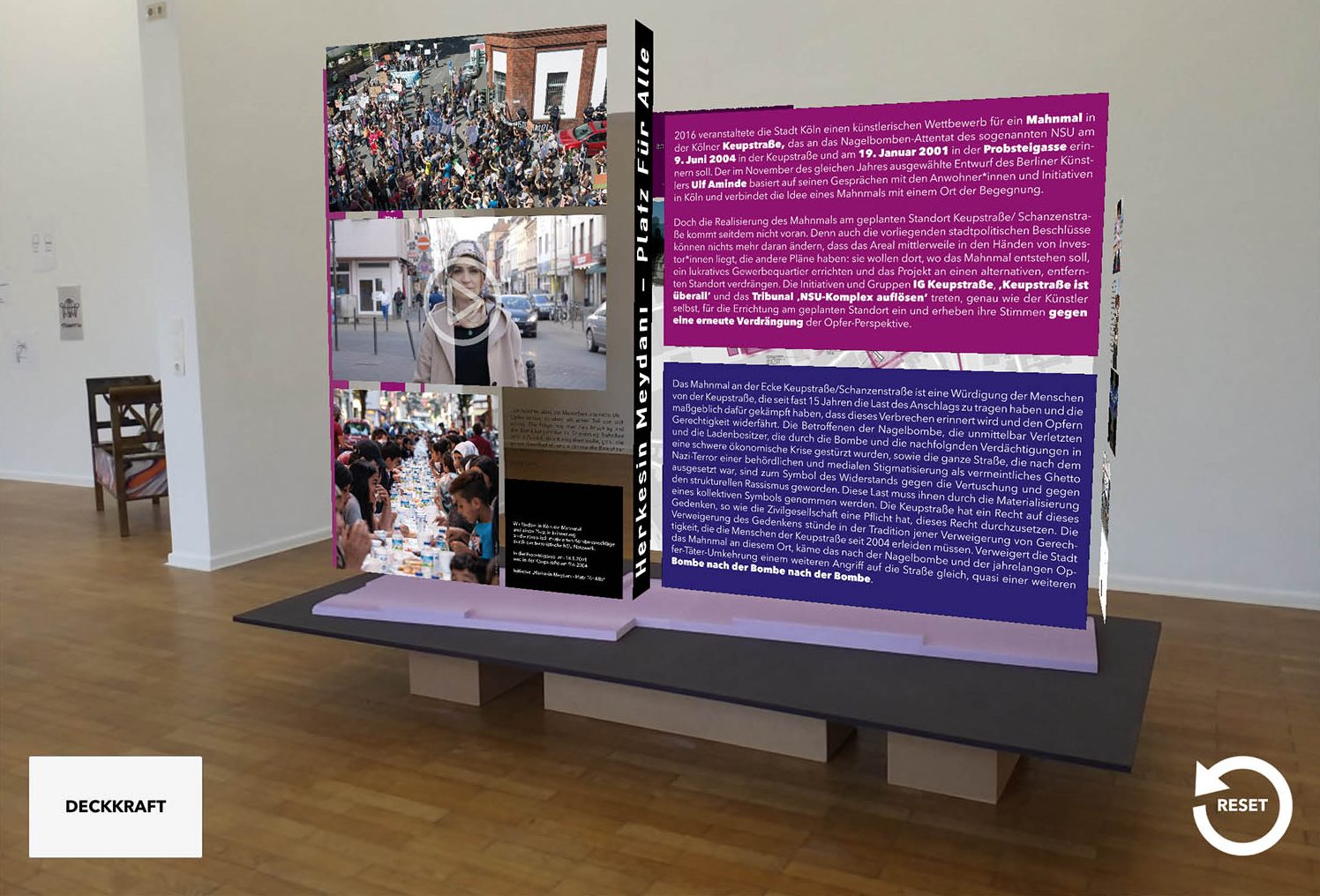

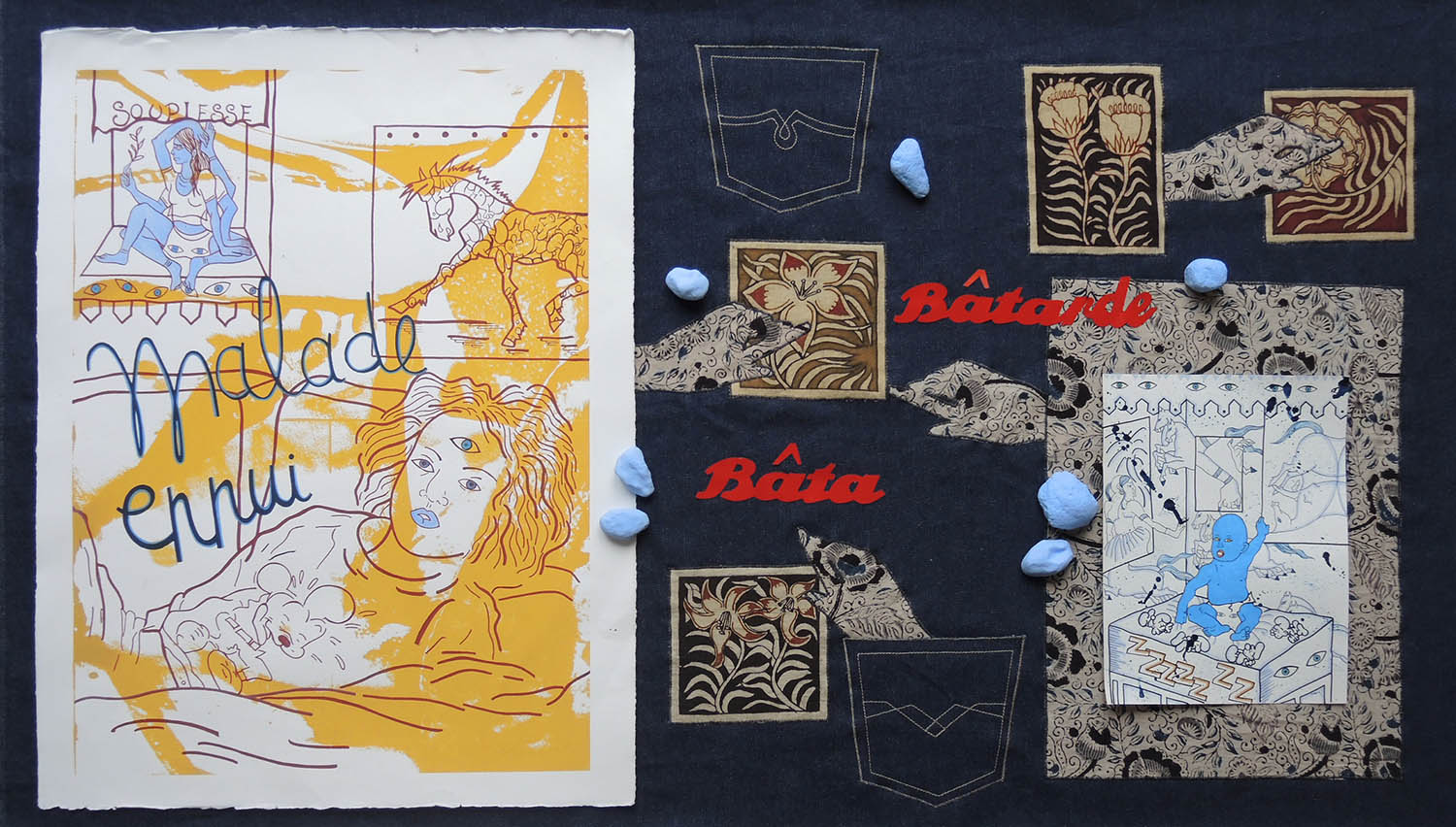

The protagonists in Austrian artist Oliver Ressler’s photograph are middle-aged white men in business suits, piled upon one another in deep slumber, as if suddenly overcome with fatigue. But why now? Isn’t that always the question? Maybe it doesn’t matter so much what exactly caused their incapacitation; the image shows that globalized capitalism will not rest until everyone and everything is exhausted and exploited to the max. Another central piece is an interactive architectural model by Ulf Aminde, based on the floor plan for a memorial for the victims of two attacks by the National Socialist underground (NSU) in the years 2001 and 2004 in Cologne. Originally commissioned as a public artwork by the city of Cologne, it was never realized due to lack of local political and public support. On a tablet computer, visitors can see the walls of one of the destroyed buildings reemerge, with projected videos telling the stories of the victims. In the exhibition it serves as a reminder not only of the victims of NSU terror, but of a public desire to repress unwanted memories: not only of the hideous murders themselves, but of the German state’s inability, to this day, to deal with deep layers of structural racism. Refreshingly easy and beautiful, multiculturalism sees a revival in the paintings of French-Indian artist Nadira Husain, as expressed in her choice of motifs, materials, artistic methods, and craftsmanship. Western pop, indigenous Indian motifs, and Japanese ornaments are interlaced with denim, stickers, or painted stones, only seemingly naive. Rather, her works here are extremely successful in showing the redundancy of insisting in the importance of nationalized ideas of art. It’s in moments like these, marveling at these works, that the whole impact of Stange’s idea takes form. Maybe a critical populism is possible.