Fourteen30 Contemporary looks out on a single tree, oddly planted on pavement too narrow for its girth. Inside the gallery appears to be empty, except for a stapled text, lying on a deep windowsill. The paper is busy with words, punctuated by §’s, symbols that convey that philosophy is near. The words unfold, five pages long, while the room stays empty. Yet the text, Lines and Lacunae: The Deep History of Drawing in Thought, commissioned by the artist, prompts a subtle re-articulation of the gallery as a space in the mind, a site on which drawing becomes the trace of thinking.¹

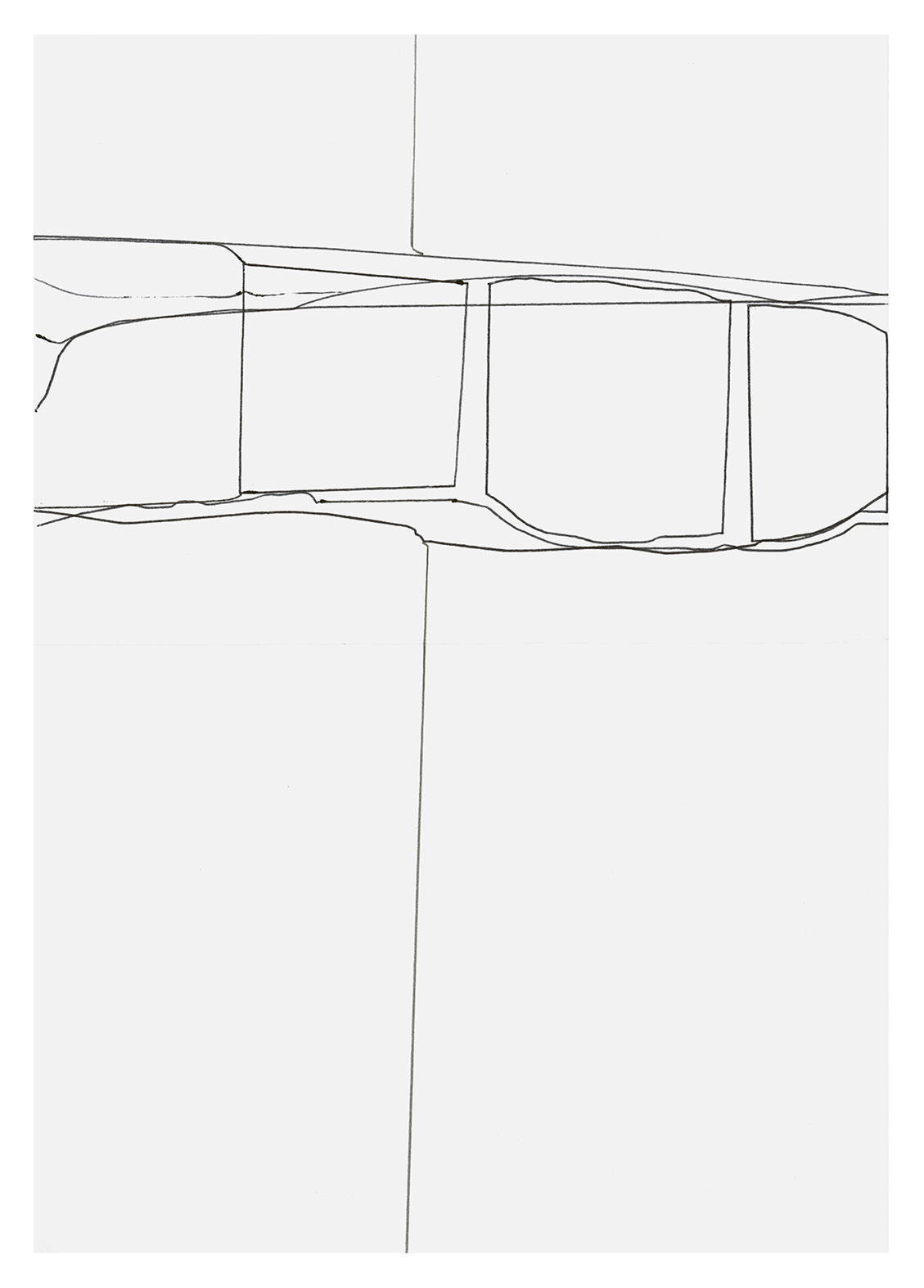

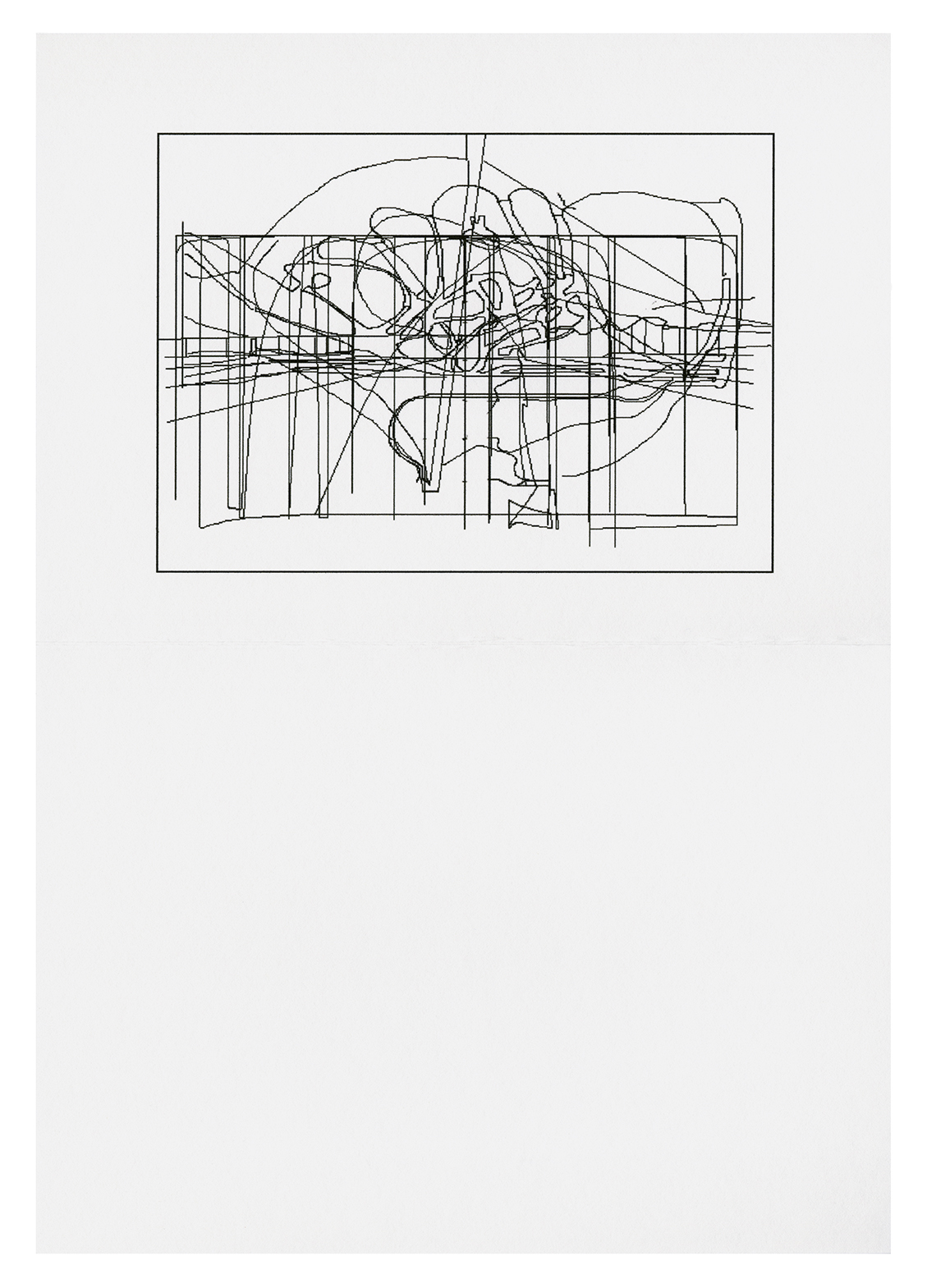

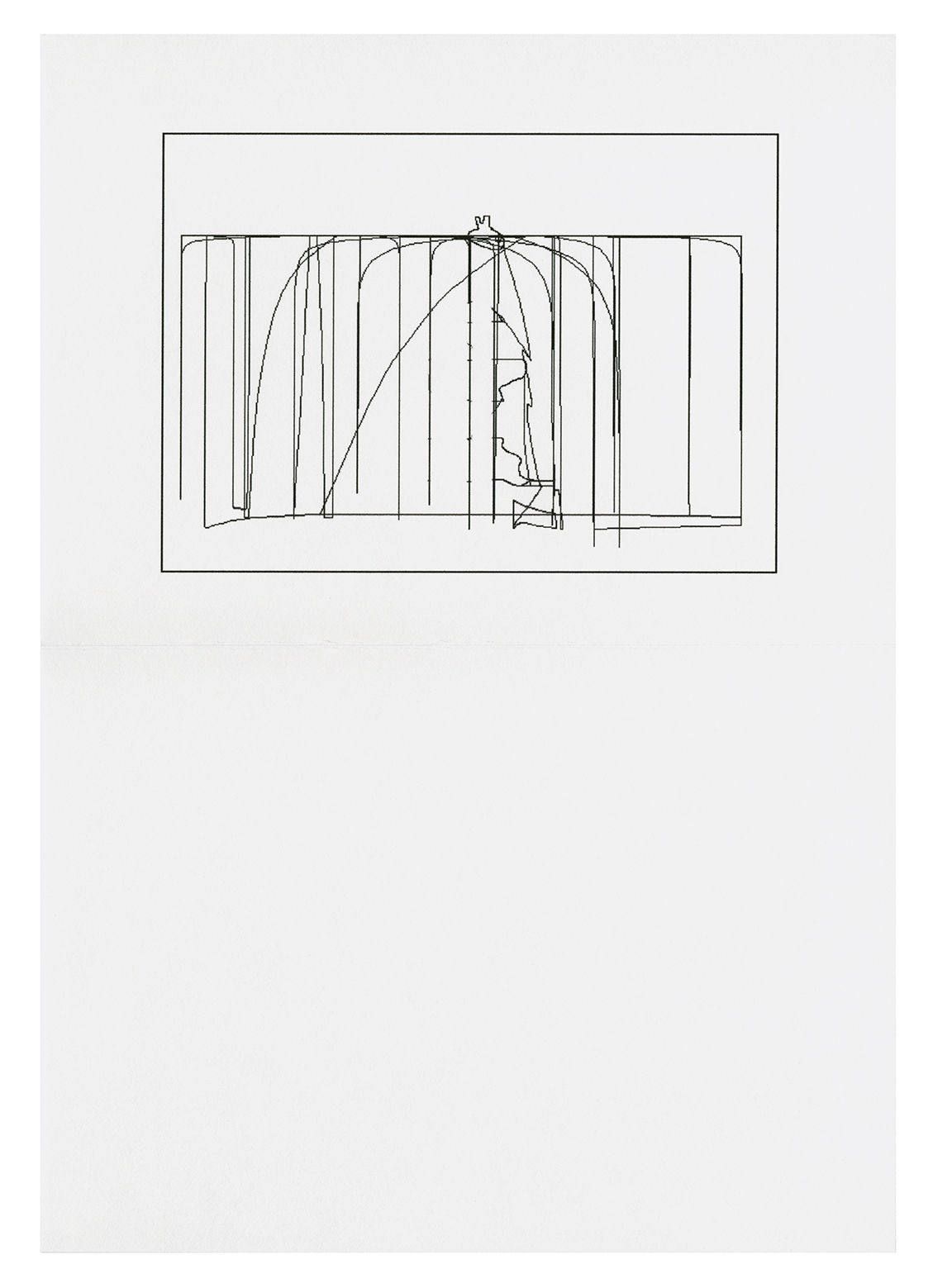

The back wall of the gallery consists of a sliding panel, usually kept shut. Today it is open, revealing a small kitchen unit. At this moment it feels as if the gallery space exists for the sole purpose of framing that opening, which in turn is made to frame that unit. On the countertop lies a binder of the kind that often presents the titles and prices of works in a private gallery. Yet, unexpectedly, an entire exhibition of drawings by Halverson is contained within it. Placed in transparent sleeves, these drawings are choreographed into an order that implies a narrative sequence, charting the breakdown and re-appearance of lines that undulate in and out of the architectural, the machine-like and the abstract.

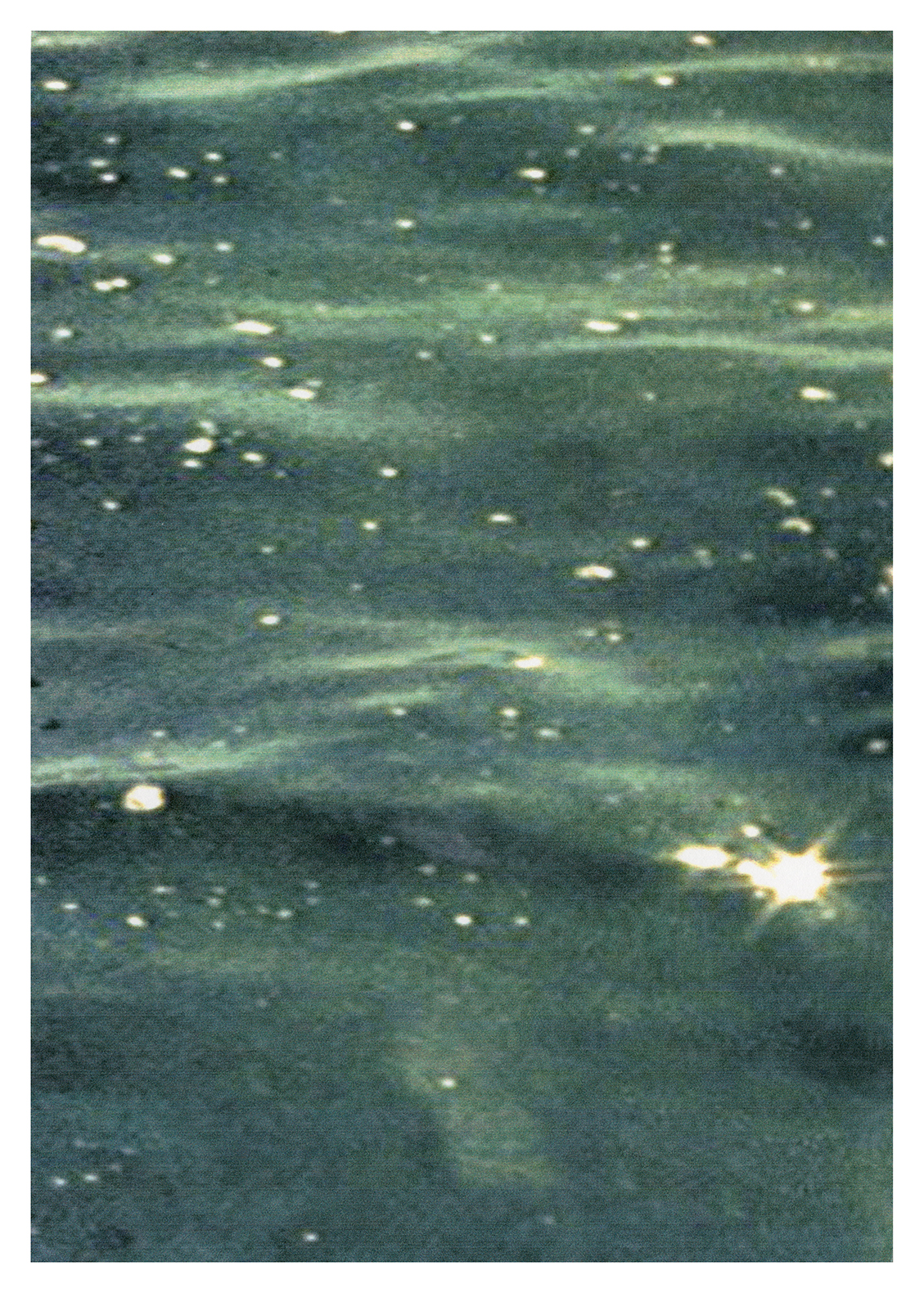

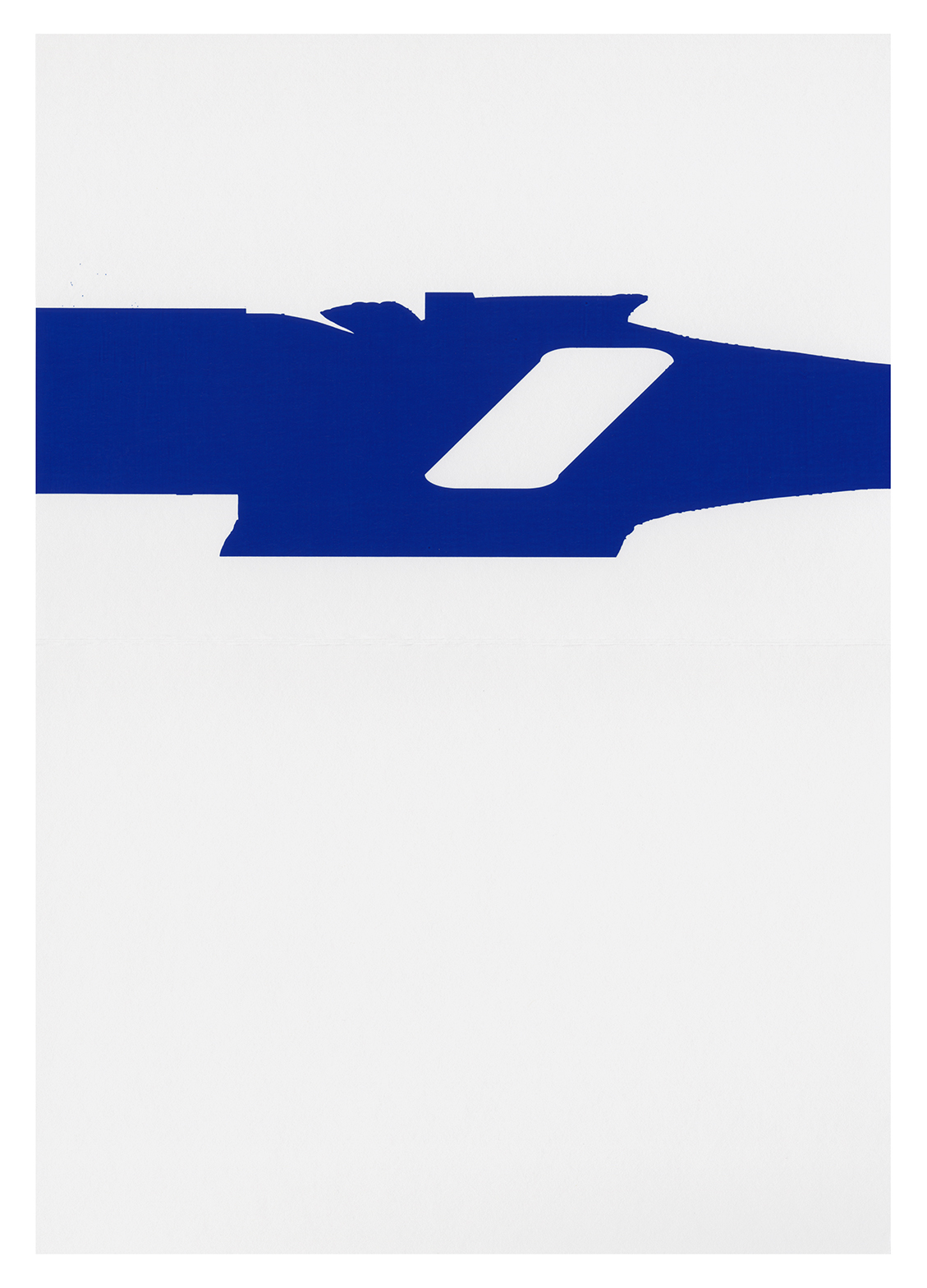

The appearance of actual drawings interrupts the exhibition of the empty room as a drawing, yet it converses silently with Reza Negarestani’s text. There is something language-like in Halverson’s drawings, however abstract. While the texts that make up their titles appear strangely unrelated to the drawings, they evoke the open-endedness of the whole encounter: “Interpretation of the Fool”; “And the next and the next and the next.” I ask Halverson if the fool relates to the tarot card, which signals starting a journey in a state of unknowing. He smiles, pleased with my recognition. The sequence of line drawings is interrupted by a hazy printed image of water (a close-up of an album cover by Hans-Joachim Roedelius), and later by a sky-blue monochrome, giving a sense of being thrown into openness after navigating an intricate line through the preceding images.

Halverson has removed all of the doors of the kitchen unit, a detail that escapes me at first. The entire show is an exercise in precision and ambiguity. Each closer examination reveals another hidden gesture: a hand drawing that is actually computer-printed, an apparent repetition that insists on its difference. Each gesture is a further remove from self, from nature and from artistry as expression. Rather, the exhibition makes manifest that drawing is the opening of form; it creates an incessant meta-instability that never stops preceding and extending itself beyond itself.²