Lodovico Pignatti Morano in conversation with Nanni Balestrini

Lodovico Pignatti Morano: I’d like to focus in this interview on the years between 1979 and 1984 and the effect of what happened during this time in Milan. For me these are years that signal at the same time the dramatic decrease in vitality of the movement in which you participated, and the emergence of a new generation who used the immanent and accessible creativity of the city in a very different way, giving birth, in many ways, to contemporary Milan’s identity.

Nanni Balestrini: I was born in Milan, but have not always lived here; in 1962 or 1963 I moved to Rome. At the beginning of the decade I’d started working at Feltrinelli [the publishing house] and after a few years became responsible for their Rome office and remained there until Giangiacomo Feltrinelli’s death in 1972. Then I returned to Milan and remained there for a few years, because in Milan I’d begun a project, a publishing group called Area, made up of various small publishers, specifically publishers with a left-wing orientation. This project lasted a few years and was then closed because of political intimidation and pressure, searches and threats.

LPM: And this happened in 1979?

NB: Yes, I was in Milan in 1979 on the occasion of the infamous “April 7th” — the judicial operation that brought about the arrest of militants from far-left-wing groups. I wasn’t arrested by sheer luck, because I was in Milan but was still registered in Rome, where they looked for me. I was able to leave the country and go to France where I remained for five years, until the trial, in which I was absolved even though the requested sentence had been ten years. The only evidence they had against me was that my name was found in the diary of Toni Negri.

Throughout those five years I was in France, but still maintained contact with Italy and with people who were still there.

LPM: During those years of exile you wrote The Invisibles, a book that, in the words of Bifo Berardi, tells the story of those who were “first marginalized, then rebels in refuge, and then finally disappeared in prisons or clandestine flight.” From a distance, through letters, phone calls and visits to friends, you constructed, through your literary method of collage, a record of the disappearance of your culture.

NB: I wanted to write the story of a generation, of a young militant typical of the movement of those years, from his first experiences as a student to social struggles which then led to his arrest and imprisonment.

LPM: And then in 1984 you returned to Milan.

NB: Yes. When I returned to Italy I was left truly dumbfounded because after these five years of being away I returned to find a different world. I couldn’t believe this transformation. There is even a myth that says, shortly after returning, there was a dinner for me, with about a dozen people, at the house of friends, and I was so distraught at hearing and seeing what these people were telling me that at a certain point I was taken ill and had to leave the room. Nevertheless, it is true that I was struck forcefully by this change because I had left a country where there was still a very lively political discussion happening, and upon returning I found that Milan had become the “city of tailors.”

LPM: In the newspaper L’Espresso, in 1989, you called Milan “a city of tailors. Where disorder, repression and idiocy reign.” [L’Espresso no. 40, October 8, 1989]. Why do you repeatedly use this specific word, “tailors”? Are you referring to the birth of the Milanese fashion system?

NB: Yes, the fashion system. This was something that had sprung up that hadn’t existed before. Everybody was wearing branded down jackets, branded sweaters… Everybody was thinking about how to decorate themselves. In the 1970s people certainly dressed badly! There were these military jackets, parkas and anoraks. This was a way to denounce bourgeois society, exhibitionism, conformism, luxury…

LPM: This fashion thing, this narcissism, was to you the element of greatest impact, but it wasn’t the only immediately noticeable change.

NB: Naturally language had also changed. Before, slang had been very politicized; now we had aestheticized conversations, empty, socially sophisticated. My general impression was that what had very suddenly occurred was the transformation that produced what we called “neo-capitalism,” competitive individualism. While before everything was done together and there had been this social idea of doing things together, instead now everybody had to fight for himself against everybody else. And above all there was this central, dominant idea, that the most important thing in life is money.

LPM: And who, in your opinion, were the writers who recorded and explored this terrain, which also has, from a certain point of view, a much tonally richer and more complex interiority, and produced the most interesting results?

NB: Writers like Aldo Nove, Tiziano Scarpa, Silvia Ballestra, Rossana Campo represented this epoch — great writers, who captured the atmosphere and language of the times.

LPM: Faced with this new situation, how did you try to respond with your literary, creative tools? The first novel you wrote, having returned, was L’Editore [The Publisher], a novel with perhaps the most formally elaborate structure you had yet used, and which told the story of the death of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli. Your first literary instinct, it seems, was to look back at the recent past.

NB: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli was the descendent of an extremely rich bourgeois family. He embraced communism and created an innovative publishing house. Friends with Fidel Castro, he imagined that the revolutionary movement that was stirring in Italy could have become an armed guerrilla force and he had created a clandestine group. He died in 1972 preparing the bombing of an electrical energy pylon which would have created a blackout in Milan.

My book is centered on this episode, which represented a fundamental parting of the waters in the history of the movement in the 1970s. The student movement, the peaceful movement born in universities in 1968 and which united with the workers’ movements during the “Hot Autumn” of the following year, was from the very beginning ferociously contested by the forces of the state, pushing it to arm itself to defend itself from the attacks it endured. A spiral of violence was begun, a period of diffused armed struggle, leading to the inevitable defeat of the movement, which was brutally repressed. The death of Feltrinelli for me symbolized this passage.

LPM: On the other hand I Furiosi [The Furious], your next work, beyond the extraordinarily intense ambiguity with which the story of ultras [football hooligans] is told, seemed to narrate the genealogy of the phenomenon of violence in the stadiums, making it pass through the disappearance of any possibility for solidarity within the movement.

NB: In I Furiosi there’s an example of this, when one of the characters, who had participated in the movement in the 1970s, at a certain point finds that this thing, supporting his team, is like being among his comrades in times past. He rediscovers in this thing, which he also says is a bit petty, watching people kick a ball around, but that isn’t important because of the great joy that these people have, these football fans, friendship and doing things together and this remained the only activity which, after the end of the great period of the 1970s, resisted rampant individualism.

LPM: At a certain point this character you’re talking about explains this transformation quickly and densely, in a kind of mini-history of Milan: “There were the mass arrests [then] arrived heroin a heap of people began shooting up there were 200 of us in the proletariat collective in my town and after a while there were only 2 of us left who didn’t shoot up… then little by little these new punk stories were born and on Saturdays we went to the Senegalese market and there once these punks came and were handing out flyers that said it was stupid to fall into the logic of drugs… that instead we had to find another way to respond to the shit of the city and so I started hanging around with them and was part of a group called Virus it was a radical experience there everything was radical from how we dressed to our behavior to the words we used everything had to be in line no intoxication you didn’t eat meat… with time these things grew and the virus model spawned Leoncavallo which began hosting concerts alternative culture and at the same time everywhere houses were being occupied…” He passes through all these different post-movement lifestyles before finally arriving at San Siro stadium, where “there was a good scene of people all smoking up shouting I was there to the side of the curva and I watched it captivated I said to myself look what a great party what a great way to be together.”

NB: After publishing I Furiosi a lot of people said to me: “What? Before you used to tell such beautiful stories, of heroic struggles, and now you’re telling the story of these wretched hooligans?” And I said: “I haven’t found anything else that represents situations of collectivity, which is what interests me.” I’m interested in stories where the characters speak in the first person but with a collective “I.”

Still today a lot of people ask me: “Why do you no longer write books on current affairs, on the ways of the world now?” And I reply: “About which people can I write?” And they say: “Well, there are always the precarious freelance laborers, the immigrants…” And I respond: “Yes, sure, immigrants, but each one of these has a different story, a personal story, they’re not like the factory workers at Fiat or the comrades of the 1970s.” Even these football hooligans all had, more or less, the same way of behaving, the same stories, that could be attributed to a single character, a collective hero. A freelance worker, an immigrant, has his own individual story, each one different from the other, and for this reason I wasn’t suited to telling their stories. But the world is always changing, not each time for the worse, and I’m convinced that men will know how to rediscover the joy of a collective life, liberated from the slavery of money and exploitation of the many by the few. And that there will be somebody who tells the story of their fight.

On May 1, the 2015 edition of the World’s Fair opened in Milan. The event marks the culmination of a decade of radical transformations to the city’s urban fabric, its political governance and its design, art and fashion industries, advances that have (re)affirmed Milan’s prominence among the world’s centers for economic and creative production. Yet throughout this period of flux, the management of culture has been left in the hands of private initiatives — a large network of autonomous players that lack cohesive and collective strategies. As a result, many have failed to gain recognition or influence the city’s social landscape — almost as if the “rampant individualism” that was mythologized as Milanese industriousness has now received its “apt punishment.” Flash Art editors and contributors met with three figures whose creative outputs are indissolubly tied to the city of Milan: architect, visual artist and educator Ugo La Pietra (b. 1938); fashion designer and entrepreneur Giorgio Armani (b. 1934); and writer, poet and visual artist Nanni Balestrini (b. 1935). We discussed the evolution of politics, culture and society in the city from the 1970s to the present, and questioned the nature of Milan’s internationally praised “urban modernity.”

Michele D’Aurizio in conversation with Ugo La Pietra

Michele D’Aurizio in conversation with Ugo La Pietra

Michele D’Aurizio: The Triennale di Milano recently hosted a comprehensive survey of your practice. I was moved by the fact that the exhibition opened with a video work, La grande occasione [The big chance] (1973), in which you exposed the scarcity of commissions for young practitioners. My first question is: despite all the impediments to living and working in Milan, why did you never move somewhere else? Like you, I’m an adopted Milanese. And despite the fact that I find the city hostile, in a certain sense, I am passionate about it and can’t leave it. After all, you too have often stated that Milan is a city that you love particularly…

Ugo La Pietra: I love Milan because it’s the place where I’ve always found myself wandering as if in a wild forest. I venture into the city’s reality and, sort of like an anthropologist, I discover things — not necessarily positive ones, but genuine nonetheless. I’ll share an example: lately, I’ve been conducting a research project on public lighting. I go around to different neighborhoods and discover that each street has a different lighting design. In other words, there is no project, which is very rare in Western cities…

So Milan is a fascinating city, of course horridly fascinating as well, and at the same time it embodies many contradictions. Milan’s suburbs, a landscape which I analyzed in the ’70s, is an unresolved scenario that still possesses its own values and allows for certain degrees of freedom, gaps that are for the urbanized man relief-valves, both intellectual and sometimes physical. Milan’s suburbs do not follow a monotonous and repetitive structure, as in the case of other cities, like Tokyo for example. But they boast a certain dynamism, which is not necessarily a positive attribute. This is interesting anyway, because it helps in the understanding of our cultural and political reality and reveals diversities, which can lead to opportunities for reflection and possible intervention, even if only on a speculative level.

MDA: Indeed, you’ve devoted many of your projects to unresolved spaces in the urban fabric, as in La conquista dello spazio [The conquest of space] (1971) in which you brought non-used places in Milan to the attention of citizens.

ULP: I spent fifteen years of my life working on a project for the Grande Brera, an idea developed in the ’60s by Franco Russoli [superintendent to Milan’s Monuments and City Galleries from 1973 to 1977] aimed at gathering the Pinacoteca, Palazzo Citterio, the Museum of the Risorgimento, the Botanical Garden and the Astronomical Observatory in a single museum complex. My proposal pivoted on the Botanical Garden, a place that still today remains inaccessible despite being publicly owned. My project in fact had been approved, the building site had been opened, but soon everything was suspended…

Milan is a city where it is hard to imagine any transformation. If you look around, you don’t perceive any thought, any planning. And the fascination that you and I, like many others, have towards the city, lies only in the small things. I’ve always thought that the city is damned. The last quality architectural project in Milan is Giò Ponti’s Pirelli Tower [finalized in 1958]. One can certainly register more recent phenomena, but they are all rather modest… The truth is that the many creative disciplines for which the city is renown — architecture, design, art — are not able to deeply condition its everyday reality.

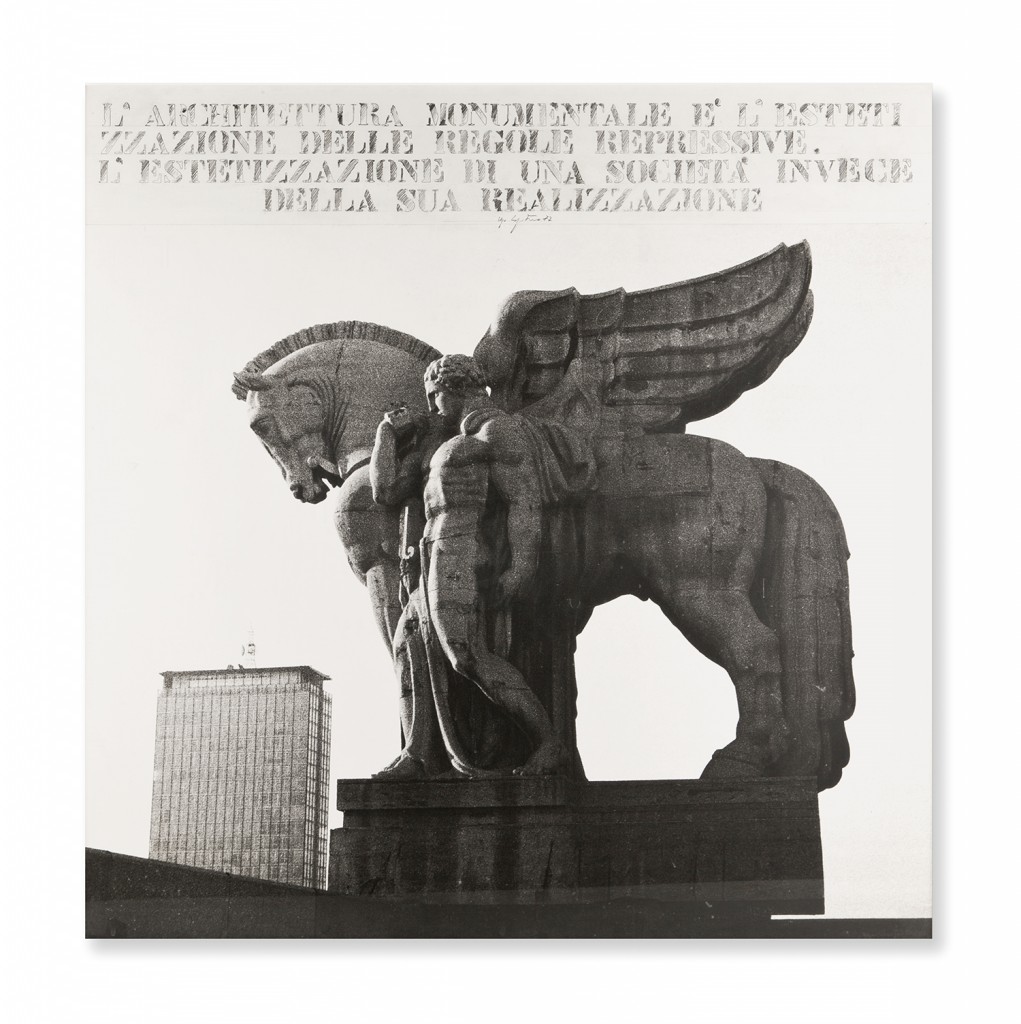

Let’s think about design: every year the greatest creative and economic efforts occur around Design Week. But this event is worse than a country festival! After a few days everything returns to normal and Milan loses its status as the infamous “world design capital.” Or about art: if you look around you recognize only awful and improperly arranged monuments. In the ’90s, Milan finally had its own Claus Oldenburg monument [Needle, Thread and Knot, created with Coosje van Bruggen, was inaugurated in 2000]. But Oldenburg has been doing monuments in every city in the world since the end of the ’50s. That shows that the little Milan gets, it gets rather late. Similarly, we have four skyscrapers, and we applaud ourselves for having them, even though every African city has at least two hundred! Milan has instead a genius loci that suggests the opposite: it’s a plain city, a horizontal city.

MDA: But who or what would you charge with this slow pace of cultural progress?

ULP: The abandonment of cultural values is a phenomenon that perhaps emerged in the first half of the ’80s. In the ’60s and ’70s, Milan used to have a very lively cultural life: art centers, associations, squats were everywhere.

In the past, the small businessman, like the artist, existed outside of power games: Milan was a city where everyone was a self-made man, a player independent from political intrigues. The cultural decadence of the city is concomitant with the historical moment when Bettino Craxi was elected Prime Minister [in 1983] and brought Milan to Rome, depriving the city of its character of isolation from politics, bureaucracy, from what the people call “mafias.” Today the entrepreneurial attitude, which is a typical trait of Milan, doesn’t boast anymore the dynamism that had distinguished it in the past.

MDA: I think about the various projects I’ve developed in the city, the fact that I’ve not been made to feel guilty about the many mistakes I’ve made out of inexperience, because I’ve remained energized and active. Do you not think that this entrepreneurial attitude may still have a positive side?

ULP: There’s still a certain industriousness in the DNA of Milan’s natives, but the system often limits it, and initiatives are commonly discouraged. People of value have constantly emerged — let’s think about Bruno Munari, a genius who hasn’t left a single mark! Like him, many pass through Milan but are barely able to affect the landscape; or they are limited to working on intimate, restricted platforms. I believe I’m a clear example of this dynamic. I’ve always worked and I’ll keep on working. Still, at my age [seventy-six] I am active with several things, and I do everything alone, because I commission my so-called “works” myself.

Every day we see Milan growing thanks to the conduct of mayors who people believe are enlightened. But those mayors are like all politicians, that is to say, they need money in order to sustain their own political program. And in order to receive those “investments” they are ready to compromise in the meanest way imaginable — like “sell off” a piece of the city to the Chinese community for wholesale commerce [Chinatown, a neighborhood in Zone 1]. But in an urban center wholesale commerce is an illegal activity — it’s an activity that is done in ports. And what’s more, the main strip of the neighborhood, via Paolo Sarpi, has been transformed into a pedestrian area [in 2011], but still continues anyway to be used for the loading and unloading of goods. Why is it that such a flagrant expression of illegality is left unpunished? [Indeed, in the neighborhood, regulations on the hours of loading and unloading and vehicle circulation are constantly violated without any efficient oversight from the Municipality — Ed.]

But this is a rather normal circumstance in our society, where politics favors forms of illegality in order to earn more money the quickest way possible. Our society is founded on a prevailing system of illegality, so widespread that today the many people who vote for parties, that is the 40% of the voters, are directly or indirectly associated with them because of some economic or professional relationship. If parties weren’t those tentacular structures that penetrate any corner of society, no one would vote for them. We Italians can still boast a strong creative selfhood; that is, compared to other populations, we have a strong sense of individuality that allows for a creative agency higher than the average people. The truth is that we haven’t lost that agency. Rather, we are unable to act on it because of the system.

MDA: This leads to a topic related to the teaching of the so-called “creative” disciplines. Among the many schools where you have taught is the Milan Politecnico. I studied there, I wanted to be an architect, but after a few years I left the school because I didn’t agree with the teaching method’s professionalizing attitude. I felt as if I had been thrown into a building site, while I probably needed to pursue a more speculative approach…

ULP: I’ve taught in universities for years, but after a while I stopped — I left the Politecnico last year. Among many reasons, because I found the Italian academic environment so disgusting…

Since the Postwar period universities have been founded in every Italian city, from Bari to Genoa. And it has never happened — and I say never — that a university professor, who happens to be in the unique position of being free from political pressure because of his institutional position, has commented on the disfigurement to which the Italian landscape has been subjected in the last decades. I’m not saying that he must occupy building sites, but at least expose what is happening. Every housewife knows who’s responsible for the devastation of the landscape. Not the politicians, who have their jobs of selling and being sold; not the developers, who have plots to fill… It is the intellectuals who have the greatest responsibility!

In 1962 or 1963 we occupied the Politecnico’s department of architecture — a joyful and apolitical occupation. And in this context we organized an exhibition of the eyesores built by our teachers. That was the only time in which somebody drew attention to what was happening to the landscape with a critical attitude, rather than the laudatory one which architects receive today. Unfortunately very few raise their voices for what everybody considers to lack value. But indignation is a cultural phenomenon that is not tied to any age or political faith: it is a critical attitude toward our everyday reality. And it should be a daily practice, pursued by all of us.

Gea Politi in conversation with Giorgio Armani

Gea Politi: I’d like to start by talking about partnerships and collaborations, a constant in your way of working from the 1980s on. In 1999 you produced Martin Scorsese’s documentary My Voyage to Italy. You also worked with the director on commercials for your fashion brand. Throughout your career you have worked with other stylists, directors, architects and others. Have you always had this idea of partnership in mind, right from the start? Is this one of the reasons why you are going to open an exhibition space in Milan?

Giorgio Armani: I think that partnership is the essence of all creative work; dialogue and the exchange of ideas are always enriching. In my career I have had the privilege of entering into dialogue with great artists, actors, architects and directors, and I have discovered some kindred spirits. I have drawn on this dialogue in coming up with the idea for the Armani/Silos, which is not intended to be a museum in the classic sense of the term, or merely a celebration of my own achievements, but a space where the clothes and accessories on exhibit and the entire heritage of know-how I have acquired over the years can be a topic for study and reflection, and a call to action for people who would like to attempt this difficult but exciting profession.

GP: What changes have you seen in the world of business in Milan and in the fashion profession since you started out in 1975? Are these changes primarily due to politics, or has there been social change too?

GA: Politics doesn’t have a lot to do with it. The fashion system has changed radically, just as society as a whole has changed. Everything moves very fast today, and the law of profit rules, suffocating creativity and risk. Fashion is now a system that doesn’t allow for the kind of ingenuity I had when I first started out. It’s all planned, and there’s practically no room for the kinds of mistakes that help you to grow. But I’m still convinced that if you work hard you can make it, finding your own path. You just have to be determined.

GP: We all know that Milan is a city that is hard to win over. You are practically Milanese yourself; what do you think of the city today, and how much has your world-wide success contributed to making your brand one of the few truly Milanese brands of the last forty years?

GA: Milan certainly is a difficult city, but it is also open to those who have the will and the determination to get to know it. It is a city that has evolved a lot over the years and grown unceasingly; in this sense it represents the very idea of modernity. As far as I’m concerned, I have a privileged relationship with the city of Milan. I breathe its sobriety and industriousness, which I have translated into an international style. I can say Milan has contributed to my success. And I have an ongoing dialogue with the city, which never ceases to inspire me.

GP: Are you still interested in keeping track of young stylists? Who are the most intriguing figures in fashion today?

GA: I’m very curious about the work of the new generations, to the extent that I have decided to support emerging talents by hosting a fashion show for an up-and-coming designer in my theater every year. I choose the designers, and they’re often creators who are very distant from me in terms of vision, approach and style; once again, I consider dialogue fundamental. I am very curious about the work of people who demonstrate that they have a bold, original point of view and are not afraid to explore it and express it consistently.

GP: Milan has plenty of institutions founded by great fashion stylists, such as the Trussardi Foundation and the Prada Foundation, institutions oriented toward contemporary art. Will Armani/Silos be mostly concerned with fashion and design, or with art as well? And if so, what genre?

GA: I believe diversification is an expression of wealth. The Trussardi Foundation and the Prada Foundation do great work in the area of art, and I don’t intend to go into this niche. I see Armani/Silos as a center for research revolving around fashion and design; it will also look at the associated art forms of photography and film, which are an integral part of my vision, and which fit perfectly into this concept of an exhibition space. I would like to emphasize and develop its identity as a vital space for students, because Armani/Silos is meant to be a constructive institution.

GP: Does the city of Milan welcome the Armani/Silos project? Which institutions have most energetically supported your vision?

GA: The project has been enthusiastically received by the city government, which will include it in the city’s promoted network of museums. We will come up with a carefully planned program of cultural events in partnership with the city.

GP: What are you planning for your first exhibition? And which other fashion designers do you intend to host in the Armani/Silos?

GA: The first presentation will be a wide-ranging exhibition about my work, in the broadest sense, not in chronological order but focusing on a number of themes that have always been key to what I do, from exoticism to the use of color and non-color. It’s too early to say what the other exhibitions will be about after that.

GP: The many initiatives at the Armani/Silos include workshops for young stylists. Do you think we are in need of a new educational model beyond the fashion schools already present in Milan? What is the educational role of the space?

GA: I have absolutely no intention of this project in any way taking the place of the existing schools — there are plenty of good fashion schools in Milan. What I want to do, though, is offer unique tools for research and study, offering precious material based on my own experience. Armani/Silos will, I hope, offer concrete, documented support for fashion education in Milan.

GP: I saw your exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York in 2001, mapping twenty-five years of work in fashion. What do you think of that exhibition today? Is there anything you would change, apart from adding the last decade’s creations?

GA: I think that exhibition is still very relevant today, not least because it underlined the timelessness of my work, an aspect which, along with the themes that have always inspired me, will also be apparent in the exhibition at the Armani/Silos.

GP: You once said in an interview that you had started designing after seeing Yves Saint Laurent’s sketches. Which of today’s artists or stylists inspire you the most?

GA: Reality inspires me: I attempt to satisfy real needs with concrete, elegant fashion. I think that if you want to create an original idiom you shouldn’t look at what others do, though you will be aware of it all. Having said this, I have a lot of respect for Saint Laurent and for Coco Chanel, precisely because they created their own style on the basis of real life, not working on absurd fantasies that will only be seen on the glossy pages of magazines. Fashion is worthy of the name only when it has an impact on people’s everyday lives: this was the case with Chanel’s jacket-cardigans, Saint Laurent’s safari jackets and Rive Gauche, and, I like to think, has always been, and is still, the case with my own jackets and suits.