Dance Office is a column dedicated to contemporary dance and performance art.

Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Berlin/Cologne/New York.

Anne Imhof’s much-anticipated new work presented at Tate Modern over ten days and five nights sits uneasily between poles of sensory production that are critical to contemporary live work: theater and reality, performance and truth. Like her recent oeuvre, this work is again operatic in form, not simply through references — which include ecclesiastical chanting, symphonic post-rock, and live vocals by a tragic prima donna — but more critically in its use of staging to create a highly dramatized situation. This staging might initially seem to erase the existence of a fourth wall, only to later reveal the work as being full of various forms of physical and emotional separation. Imhof has cunningly titled this piece Sex (2019) — itself an activity that is no stranger to other public and private forms of performance and display, or to the seemingly contradictory experience of pleasure as pain.

If we were to locate a beginning, Imhof’s Sex is arguably put into motion in a room that features the near-constant use of strobe lights. Here, audiences stand on a barricaded platform and the performers move below them. Initially they do so in a pack, standing together in front of and beside the structure. Making the group visible in its near totality renders it as both a snapshot of Imhof’s cast and as the body politic of the situation she has constructed. From here on they separate, moving into different rooms. One room features another platform, now inaccessible to audiences, and the last set of rooms appear more like an exhibition space: a place for the display of both Imhof’s artworks — painting, sculpture, and installation — and her performers – themselves things on display, akin to the other objects in the room. Throughout, performers enact processes of relation that are both choreographed and dictated live by Imhof via text messaging.

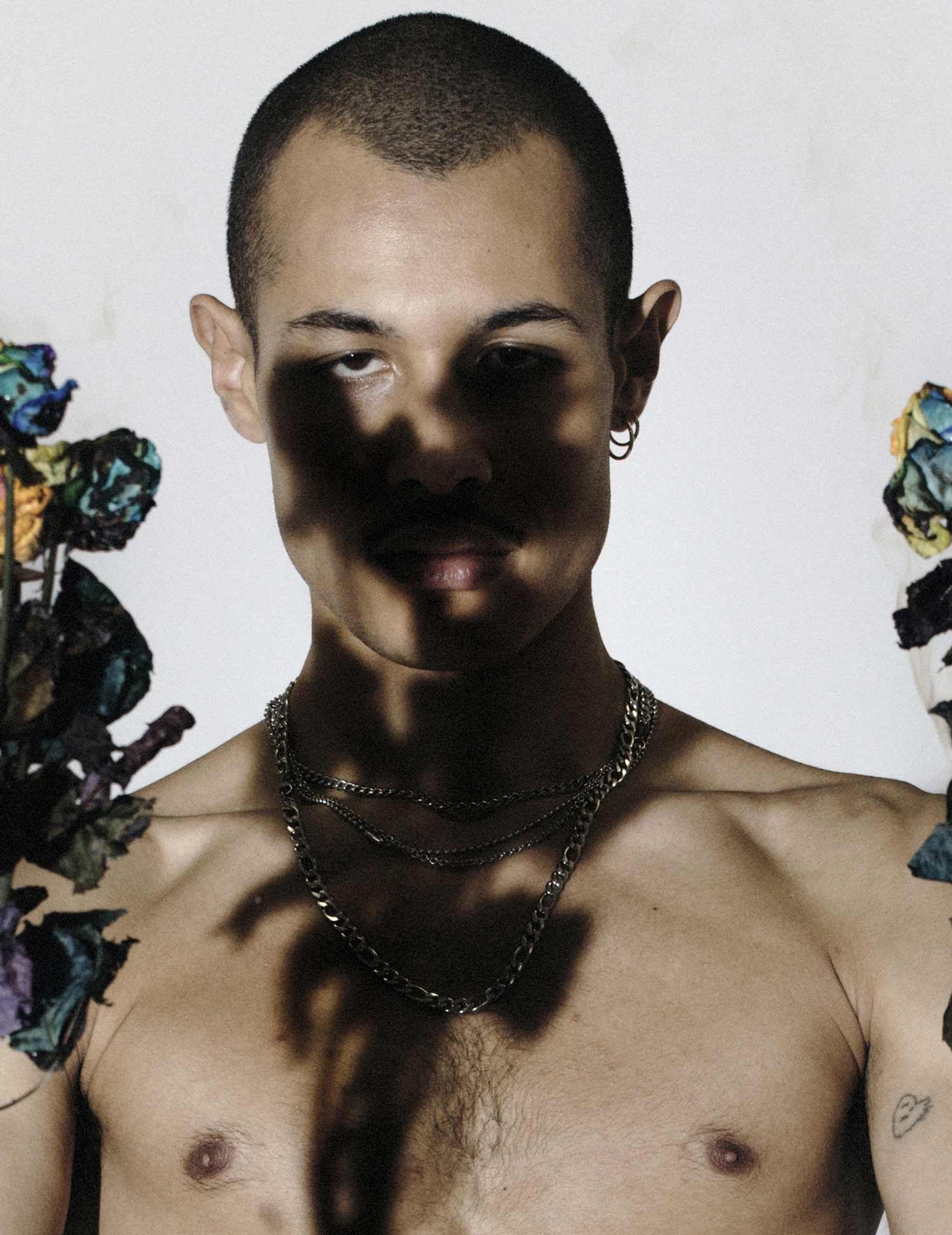

Despite the many grandiose gestures featured as part of this choreography, the work is initially unable to generate emotion beyond an admiration for the work’s scale and spectacle. Particularly memorable gestures include: one performer being carried on two performers’ shoulders in a Jesus-of-Nazareth fashion; performers taking turns jumping backward from a structure and into the hands of bodies that carry and parade them in crucifixion; walking up and down visible and invisible runaways, at times exposed to audiences and at other times sheltered by sheets of glass; burning bouquets of desiccated roses; and carrying mattresses on which performers occasionally recline or sit still, watching audiences and each other while vaping. Throughout, Eliza Douglas manifests as a religious figure, invoking attention through her presence and by singing and playing electric guitar.

That Eliza is idolized in this piece does not go unnoticed, and this is not necessarily a bad thing. Imhof and Douglas have an almost mythic public status as partners; from their various activities in the fashion-industrial-complex to the co-authoring of artworks and Douglas’s close collaboration in the making of Imhof’s performances, their relationship is as much personal as professional. Douglas’s centrality in this work is almost akin to that given to a celebrity — a notion that further materializes in the Warholian silkscreened canvases of Douglas’s face, mouth open in a guttural silent scream, numerously repeated across several panels and found hanging within one of the rooms. Her ascribed status — here on par with the likes of Marylyn Monroe — is a testament to Imhof’s vision of Douglas not just as her lover but as an iconic figure. As much as Douglas is arguably a vision of Imhof’s own making, Imhof is also made a star in the presence of her aura. Unlike Warhol’s Marylyn Diptych (1962), in which an array of colors slowly transitions into faded prints in black and white, symbolically alluding to Marylyn’s eventual tragic ending, Imhof here renders Douglas’s portrait only in gray scale, creating a feeling of perpetual tragedy. In this set of rooms there are various references to substance abuse — for example, the use of measuring scales, metal spoons, and sugar as installation props — and they further a fragile feeling of dependency between Imhof and Douglas. Their working and being together, and their willingness to make that labor and its physical and emotional toil visible, creates a queer sense of survival.

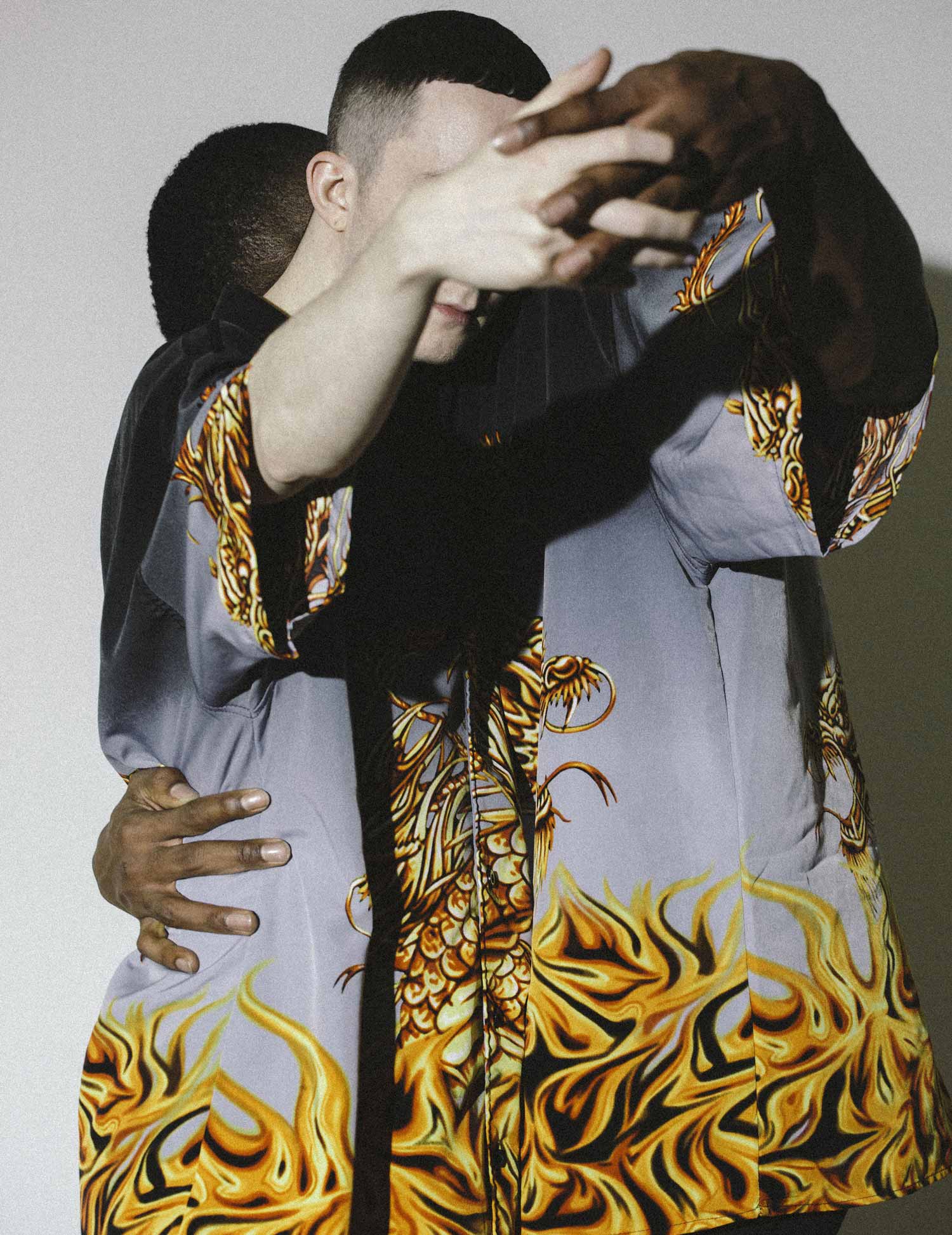

The rest of the performers are somewhat lost. This is particularly clear in their constant embodiment of an empty gaze, which is less an expression of boredom or state of being unconcerned as it is an intentional spacing out, a process that makes them seem emotionally hollow, divorced of feeling. Imhof’s vision of sex is constructed on the basis of this lack; it is built on the premise of relation as devoid of eroticism and intimacy: not just as something absent but as something to directly fight against. This renders all interactions solitary, asocial, alienated. Even when the performers share movements, as single gestures or in a group, they enact a symptomatic state of removal.

A good representation of this is when two male performers simultaneously lick their hands, extending their tongues up their wrists, leaving a small trail of saliva sticking to their body hair. Though this moment could be read as sexual, its “sex” is partly canceled out both by the performers’ refusal to connect and recognize each other’s desire, and by eliminating the experience — or even the possibility — of pleasure.

Throughout Imhof’s choreography we arrive at sex through similar processes of signification, at times akin to what is known as “spectatoring,” the modeling of behavior after what is seen onscreen. The performers focus on themselves almost as if their experience is that of a third party’s sexual activity, nullifying their own sensations and that of their partner’s through a state of anxiety. If in spectatoring this anxiety is built on the basis of a performance, provoked by what is acted out versus what is then practiced in the flesh, here the performers are nullified by their mutual representation, their actions akin to a surface: one that reaches them, and us, both physically and virtually, and that is mediated by the residue of a photographic lens, irrespective of whether we are looking or using our phones.

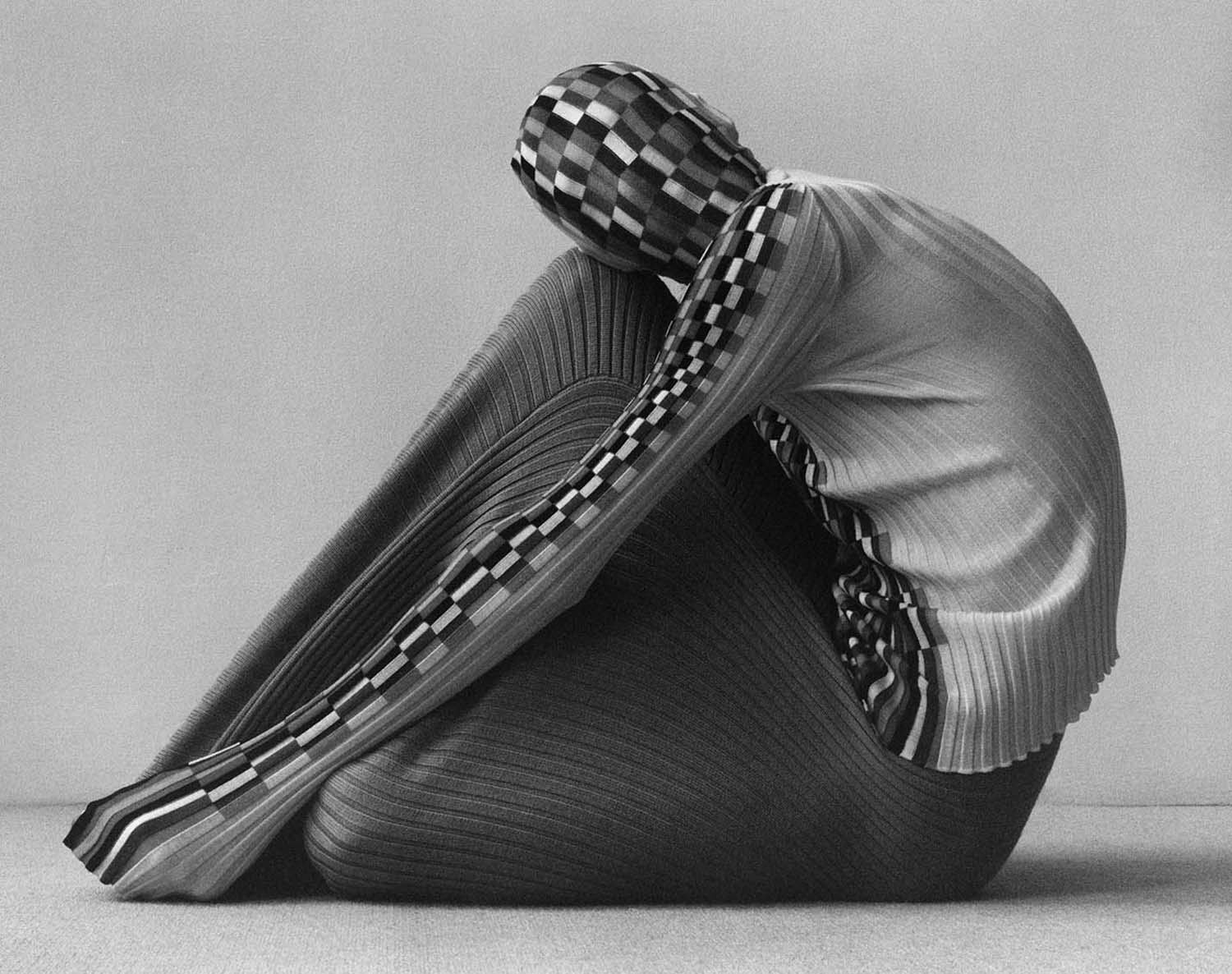

Imhof continues to fabricate this surface elsewhere via the flattening of bodies, which she best achieves through the use of strobe lights. In one room the performers enact various parts of the score under the near-constant flashing of light, including: a performer lashing a concrete wall with a long brown leather bullwhip; Eliza kneeling on an elevated mattress, shirtless, rocking her head back and forth; and other young shirtless bodies pacing with motorbike helmets on their heads, eventually removing them and dropping them loudly around the space. The flashes not only exaggerate the performer’s actions; they also reinforce the making of this surface. Imhof’s work appears therefore not merely photographic, but as a photograph, a moving cluster of images.

Via this process of making images — rather than affects — Imhof frames her work as acts of representation. This gives the performative a quality manifestly tied to “reality,” to what could be seen and understood as an extant state of depressive body politics, which Imhof’s Sex makes visible as a type of neoliberal pornography. Porn is, as German philosopher Byung-Chul Han writes, following Agamben, “a matter of bare life on display.” What Imhof gives us throughout this work — or, more precisely, what she shows us — are bodies in various states of disaffection. If the work represents the state of youth in the age of anxiety, of a particular generational struggle of finding substance, identity, and pleasure in a shifting and increasingly digital, virtual, and disembodied world, then Imhof mostly succeeds at capturing a recognizable picture. However, through the artist’s Sex we are also forced into the re-staging of these very same conditions, for Imhof replicates the forms of encounter and visuality in the age of anxiety, extending them within a highly aestheticized situation.

What troubles from Imhof’s work is the use and constant presence of narcissistic desire, which seems to be a symptom — if not itself the condition — for these choreographed situations of relational animosity. While the connections between the performers are increasingly superfluous, the constant search for our own fulfillment, as audience members, materializes in Imhof’s crafted choreography of attention, where desire is built as a condition of spectatorship for those watching. In this way, Imhof’s Sex facilitates ways of seeing, moving, and behaving that heighten our need to seek pleasure in what is happening; but not meaning.