What remains of bodies after the necrosis of capitalism? Skin and bones. Dust. And clothes, the contours of bodies that were. All are materials that recur in Davide Stucchi’s work, shaping our interpretation of a project that seeks to reaffirm the body, its mechanisms and its social function.

Stucchi calls himself a sculptor, but most of his pieces involve only minimal material interventions: subtractions, deteriorations, alterations of chemical states, subtle manipulations of existing forms. On the other hand, what can a sculptor sculpt when his human subject matter is reduced to fragments — transformed, transfigured and zombified? Relics. Which is what Stucchi’s works may, at first glance, appear to be. And yet they provoke a tension between the inert material and the spectator’s gaze that immediately refers back to life.

The piece Mattia (2015), for example, is a tan leather scrap etched with human teeth marks, as though the surface had been bitten repeatedly. The work’s title invokes the artist’s partner, a figure who relates to Stucchi’s work the way that Ross stood in relation to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s. Yet where Ross’s body is always implied in absence, Mattia’s acts and is, in turn, acted upon. Whether, within the couple’s intimate encounters, it is Mattia’s teeth that sink into Davide’s flesh or vice versa matters little; the bite marks are an index of one person’s vivifying desire for the body of another.

The crude corporeality of some of Stucchi’s output might suggest correspondences with the works of Alina Szapocznikow: excrescences of decadent and libidinous female bodies. But Stucchi doesn’t participate in Szapocznikow’s trauma — the spiral of “glamour and sickness and death”¹ that the Polish artist activates in works like Tumors Personified (1971) — and instead resorts to more sanitized images. His works may thus be deemed closer to Ull Hohn’s idealization of an immaculate epithelial surface in “Tan Enamel,” his 1993 cycle of paintings in enameled modeling paste. Yet Stucchi does not operate quite like Hohn, haunted by the ghosts of AIDS. In Stucchi’s works, the reaffirmation of the body does not pass through the exorcism of pathology so much as through the deconstruction of the corporeal ideal as expressed by advertising, fashion, consumerism: a hyper-defined and undeniably heterosexualized body that, for Stucchi, is no longer either the object of desire or the desiring subject. The artist therefore does not intervene into strategies of the body’s representation, but rather subjects “the body, its organs and fluids … to a plastic recovery.”² That is to say, he invents new ways of sculpting the body.

The masculine bodies represented in Stucchi’s work are always subtle — and not only because the artist forces processes of material reduction. Rather, he seems to want to free these bodies of any element that would transfigure them into the realm of machismo, thus rediscovering the features of a masculinity that is stripped down to the essential and therefore genuine; Pasolinian, we might say. The challenge posed here is against advertising’s image of masculinity, according to which the masculine body “is all sex organ, or aspires to be … but it’s a sex that is neither chaste nor indecent, neither natural nor conventional, because it is situated beyond such partitions. Situated, that is, in fashion,”³ where strapping bodies are, in reality, dephysicalized and decarnalized.

For his show at Deborah Schamoni in Munich, Stucchi produced an invite on which, alongside a photographic portrait of himself, he noted his measurements and facial characteristics, like on a model’s composite card.

Badly stuck to the gallery window was a copy of the invite addressed (and never delivered) to Eva Gödel, founder of the Tomorrow is Another Day modeling agency. Established in 2010, Tomorrow is Another Day is among the platforms responsible for introducing into the fashion industry a new visual paradigm of masculinity, an aesthetic traceable to the ragazzo di vita, the Pasolinian “boy of life” or hustler, abruptly transplanted from the lumpenproletariat to the catwalk — a readymade exempt from any real process of corporeal hyperdefinition.

Stucchi invokes the Tomorrow is Another Day phenomenon to show that visual culture is, indeed, increasingly supportive of the anti-macho image; at the same time, by forcing a confrontation between his own body and that of the agency’s models, he stresses that expressions of a living masculinity cannot be sought in fashion — where “indecency [is] chaste, and chastity indecent,”4 to echo Pasolini. That is, we find gender but not sexuality.

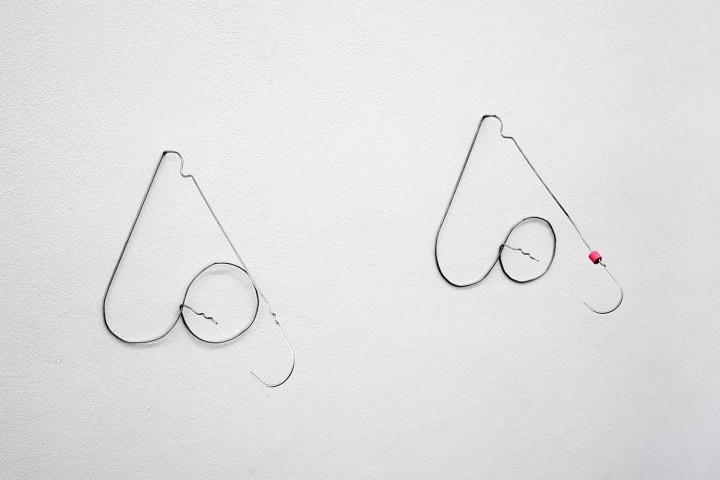

Stucchi’s exhibition in Munich is punctuated by sculptures from the series “Naso (pisello)” (Nose [penis], 2017). Made through the simple gesture of reshaping metal hangers, these are “spatial drawings” that, depending on how they are attached to the wall, evoke either the silhouette of a nose or a penis. Their stylization recalls the “‘divine’ shadows” that Professor Giubileo, in Pasolini’s homonymous story, sees cast on Moro’s pant legs by his “bas-relief”5 — while Riccetto’s “lap,” packed into his Sunday trousers in “young bourgeois” style, is immediately “chaste”6…

In Munich, the artist also invited Corrado Levi (Italian artist, architect and poet) to exhibit an old work, Cinture (Belts, 1992), here retitled to Desiderando gli amici (Desiring One’s Friends). The work is a diagonally stretched steel cable with dozens of men’s belts hanging from it. The irony of Desiderando gli amici opens the way for that of Naso (pisello) — as if to say, once the belts are confiscated, the pants have a hard time staying up. Both of these works inscribe sexuality within a framework of frivolity, play and jouissance. They trace a masculine body that might be made of signifiers but is nonetheless alive. So alive that it invites and challenges because it knows neither indecency nor chastity. It is finally a sexual body.

Subjecting the masculine body to a process that is reductive both of its substance and symbolic weight means depriving it of muscles. This is the path that Stucchi pursues: stripping masculine bodies not of the muscle mass proper to a healthy physique, but of unnatural, constructed, aestheticized muscles.

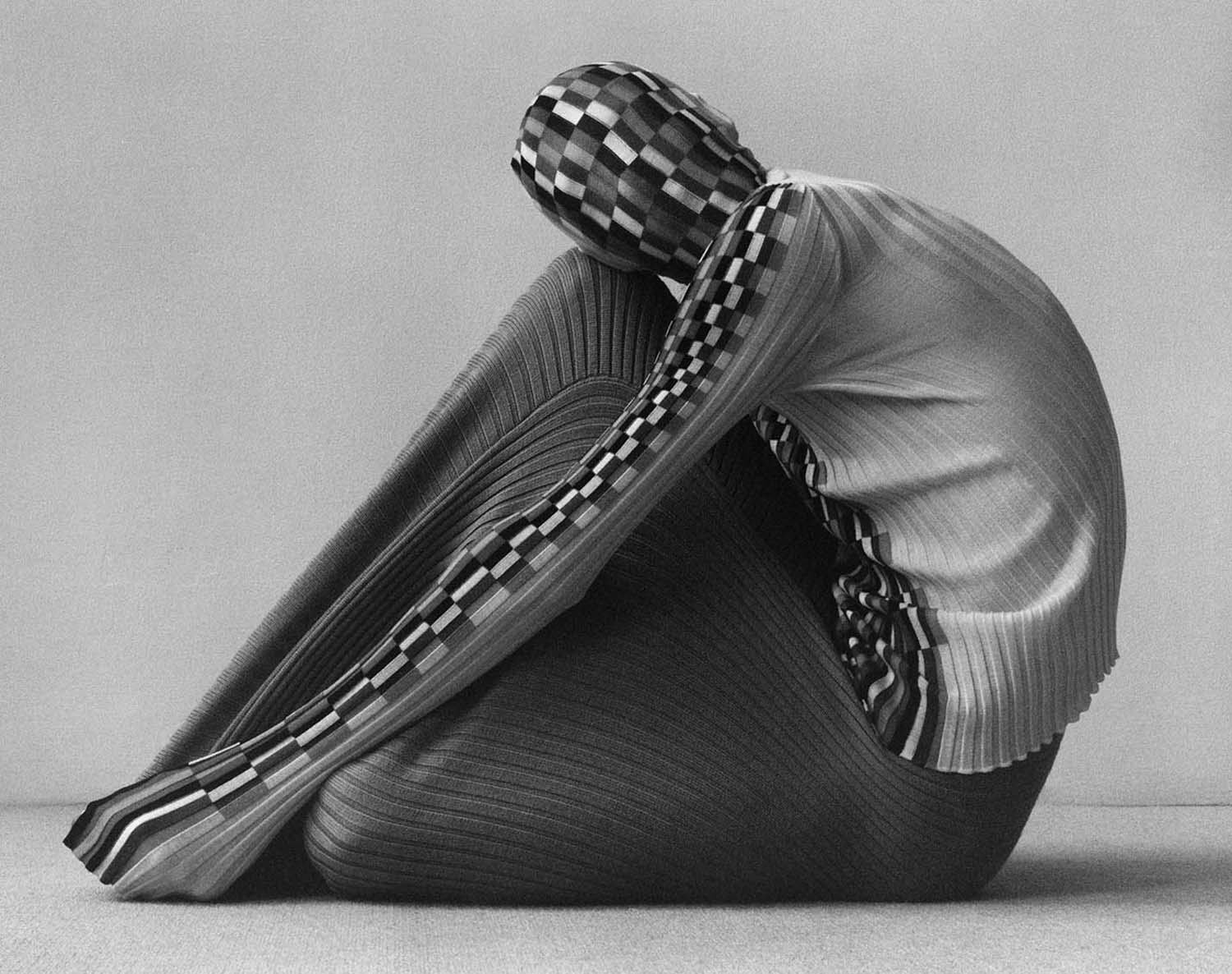

In homosexual slang, the masculine body without muscles is that of the twink. A twink is the opposite of a bear, beefy and hairy. The bear is markedly masculine, the twink effeminate. Last year, Stucchi made a piece titled Heat Dispersion (Mattia e Davide)(2016), two soap casts of the bodies of the artist and his partner, Mattia. In the piece the two naked bodies lie belly down; you can’t see their physiognomy, but they appear long-limbed and slight — two twink bodies.

Heat Dispersion is an elegy to “effeminate masculine” love, twink love. Here, the simple act of cleaning the imperfections left over from the casting process is akin to caring for the body: one’s own but above all that of the other. It replicates the amorous gesture of bathing someone. At the same time, the perishability of the soap implies that such care, if excessive, can cause the sculpture itself to perish. Before making Heat Dispersion, Stucchi confided that he would have liked to “wash” the casts in the sea once they were finished, to the point of reducing the bodies to formless masses. With this gesture, he would have used ceremony to transcend any representation; but by way of such ceremony, he would have subordinated the reality of the couple to the birth of the work. Heat Dispersion instead exists to testify that the creative act is not always or necessarily “productive” — just as the sexual act, in gay sex, is not procreative.

In this work, the material instability of soap translates into a tension that resides in the physicality of the two bodies. They sleep, but we know that they desire each other. Just like we ourselves desire to touch them, because soap engages our sense of touch. How should we act, then, when faced with their “nudity”? In an era in which the average gay, in order to individuate a sexual partner, communicates his identity as a masc-4-masc — is, in other words, a “male” looking for another “male” — the physicality of these two twink lovers reaffirms the extent to which gay subjectivity is legitimately the result of a dialectics of masculine and feminine. Embracing this equivocation is what allows us to abandon normative representations of sexuality. And thus evolve our ways of living the body, of feeling and representing it.