“Emerson” introduces the first chapter of the new column “Non Conventional Modes of Curating.” “Emerson” works as an introduction to the unconventional – it is an apartment and home to the idiosyncrasies of the non conventional gallery and curatorial practices. The works of the artists sit on the walls, almost as a service to the apartment, and its inhabitant(s). Here, the apartment ‘lives’ with the exhibition, and gives context to the artwork.

The gesture of an invitation into the home of another is categorically imbued with a sense of intimacy. Being in the living space of others is as potentially revealing of one’s character as, say, a drunken conversation in which too much is divulged in the spirit of oversharing. Personal curation is inherent in the objects we own and how they are placed: from the way a cushion is scattered, to how laundry is folded (or not folded), to which stylish and intellectual books are chosen to sit on a shelf most prominently.

With consideration to the curated nature of personal space, it follows logically that it is increasingly commonplace for curators to opt to use personal living spaces as a not-so-blank canvas within which an exhibition can be housed. Therein lies the concept of “Emerson,” the creative venture of Sydney-based curators Sebastian Henry-Jones and Harrison Witsey. Their premise is simple: a group of both emerging and established artists are invited to submit a piece of work to be exhibited for approximately a month. The exhibition is held within the apartment of photographer Samuel Hodge, which is sublet during periods of the year when he is overseas or otherwise absent. It is an opportunistic event, focused more on playfulness and experimentation than conforming to traditional modes of gallery presentation.

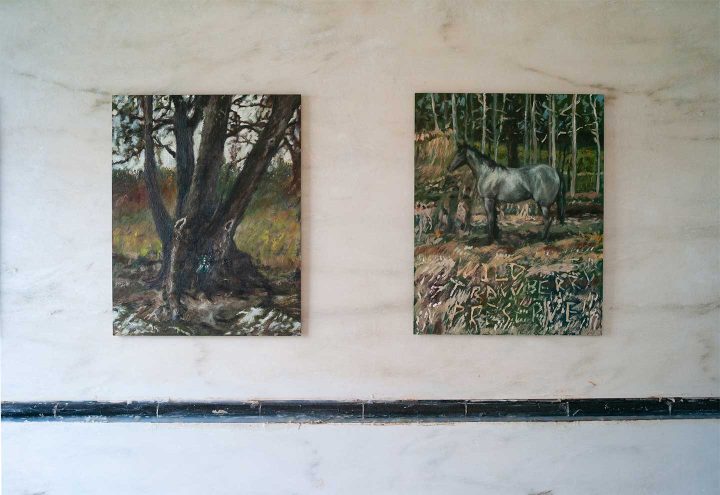

When entering the space it is difficult to determine what is part of the show and what is not. This is “the point,” so to speak. Framed photographic prints of Hodge’s remain on the walls, not specifically as part of the show but contributing to the ambience nonetheless. On the bed, a scattering of roughly stitched animal-shaped soft sculptures by Matilda Davis are laid out as if someone has slept with them the night before. Some pieces are even conventionally displayed hanging on walls.

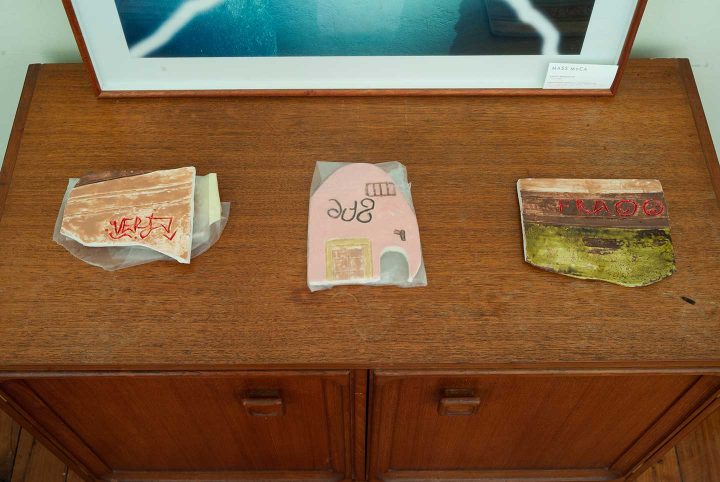

One of the stronger works in the show is a weaving by Elizabeth Pulie that can be spotted instantly upon entering the first room; its delicacy contrasts subtly with an industrial rust-colored Masonite piece by Matthew Gorgula. Three small ceramic and plastic works by Mark Mailler are placed atop a teak mid-century sideboard in the bedroom. A series of paintings by Victoria Stolz are mounted to the tiles of the shower; these are intermittently removed when Henry-Jones, who also inhabits the space as a sublettor throughout the duration of the exhibition, deigns to bathe himself.

While a checklist is provided, guests are largely left to their own devices to navigate the compact two-room space. Such a setting can feel more like a house party or inspection than an exhibition. There is no black-T-shirt-clad invigilator dictating how the show is to be experienced; no wall text; and no one to dissuade others from touching the art, the cardinal sin of gallery visitation.

The inaccessibility of rent for both gallery and living spaces in Sydney is an obvious contributing factor in the decision to house “Emerson” within an apartment. Sydney is known for its high cost of living compared to other Australian cities. Similar initiatives for artists and curators are becoming all the more necessary to facilitate experimental curatorial practices. Sydney Sydney Gallery, situated within the house of curator Conor O’Shea, is one such example. Further west in the suburb of Petersham, New Zealand–born writer, artist, and curator Talia Smith operates a conceptual gallery project named Cold Cuts Project Space out of her garage. However, as is the case with “Emerson,” these spaces do not exist solely through a lack of support for young curators. Talia Smith, for example, was last year named as a recipient of Artbank’s emerging curator initiative. A month before the opening of “Emerson,” Henry-Jones curated a successful group show titled “Do You Know This Feeling?” at Firstdraft, Sydney’s longest running artist-run initiative.

Institutional support for young artists and curators in Sydney is not unattainable. However when monetary pressures are removed from curatorial decisions — whether this is paying rent for a gallery space or otherwise having to acquire funding or subsidization — this seems to facilitate a more relaxed environment that allows for creativity and experimentation. “Emerson” is a testament to this. The lack of pressure manifests in allowing certain insecurities to dissolve, encouraging the creation of work that is diverse and experimental. Elizabeth Pulie’s weaving, for example, would not be out of place at the Museum of Contemporary Art or Sarah Cottier Gallery, by whom she is represented, but it is shown diagonally across from an ephemeral floral work by Hana Lee, who works primarily as a florist. The brief sent to the invited artists is deliberately informal; an outline of the project is ended with a disclaimer that this is an opportunity to exhibit something that the artist would not feel comfortable putting in a conventional show. The letterhead of this brief is an animated GIF of Garfield, and the document concludes with a non sequitur meme about garlic bread.

The result of this unconventional invitation is a show that is subtle, nuanced, and intimate. It is a promising follow up from Witsey and Henry-Jones, whose ability to draw together a diverse group of both established and fledgling art practitioners is a testament to their considerable curatorial skill. For now, “Emerson” will continue as an occasional event when time and circumstances permit, but its potential as a project is extensive. The curators have contemplated the possibility of showcasing more traditionally within the context of an art fair or gallery space; it seems that it is through their “Emerson” experimentation that they will gain the experience and legitimacy to do so. Perhaps the logical next step for Henry-Jones and Witsey is Spring 1883 — a yearly art fair alternating between Sydney and Melbourne in which gallerists curate small shows within hotel bedrooms. After “Emerson,” such a setting would not be their first rodeo.