Conspiracy has always existed, but it inundated the mainstream in the US only after the Second World War. Its rise was triggered by two new manifestations of power: postwar political structures turned into humongous, anonymous, and pervasive organizations whose real identity and purpose were impossible to fathom; and an unfortunate series of events, initiated by the assassination of JFK in 1963.

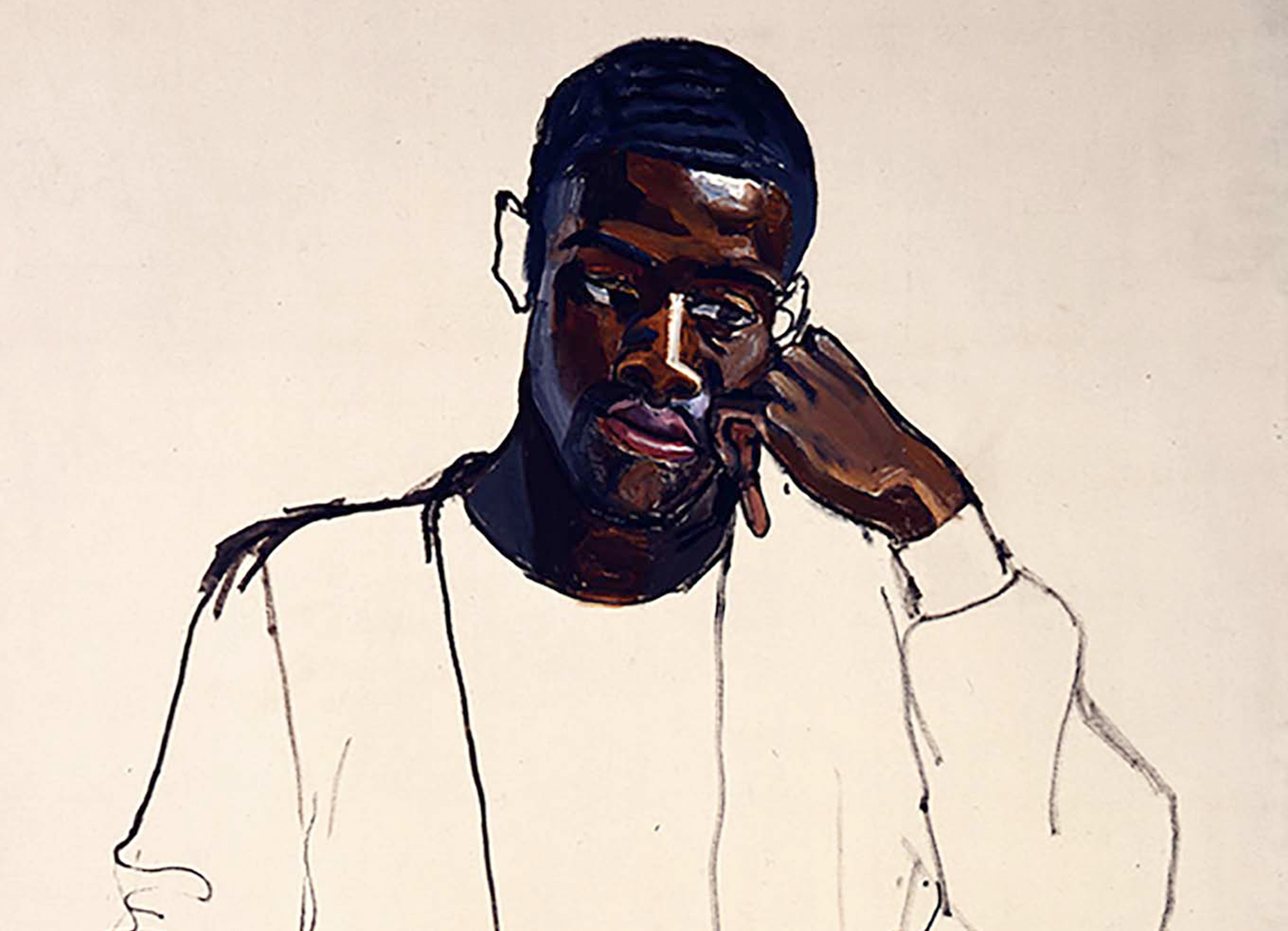

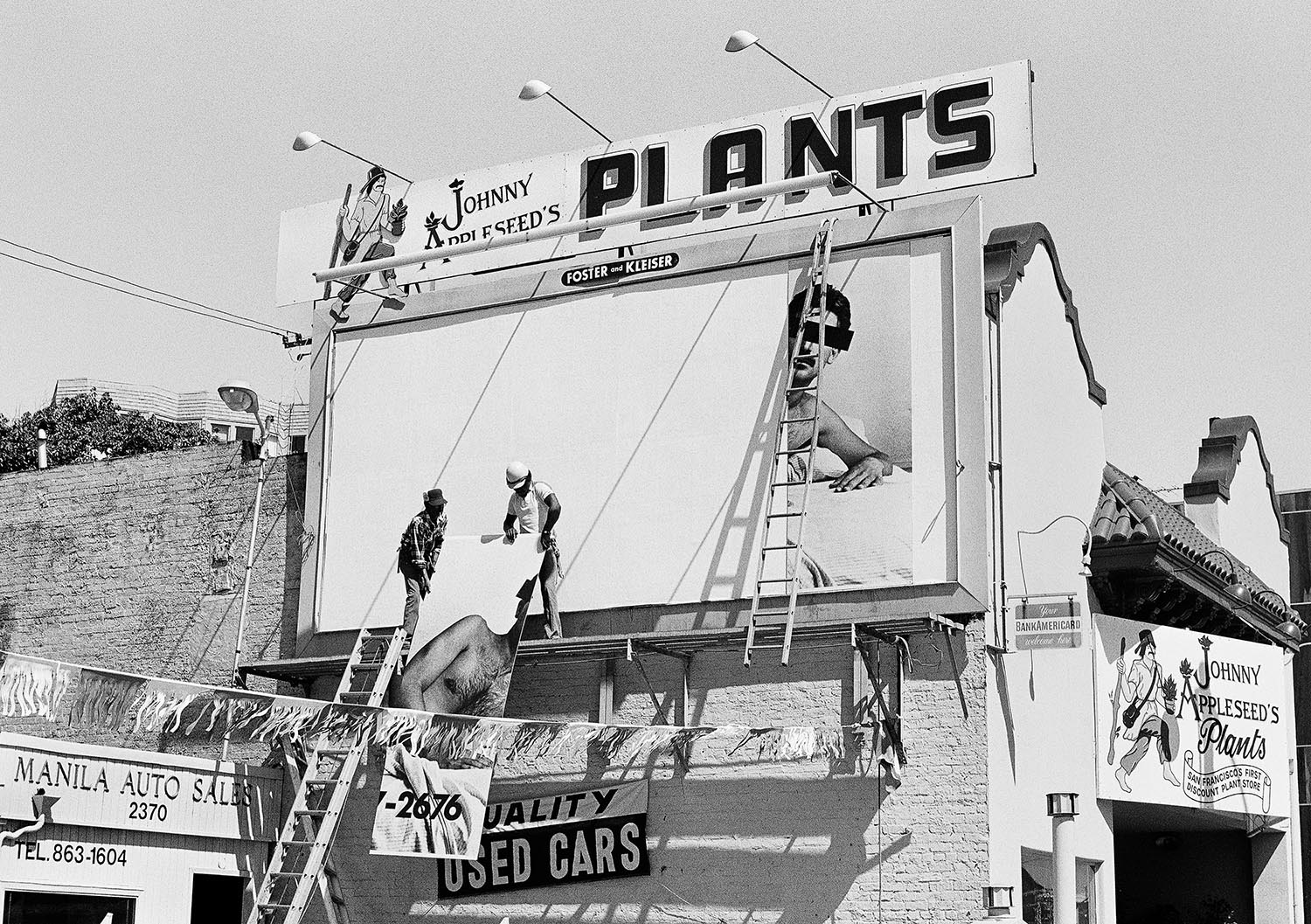

As a result, the trust Americans had in their government slowly degraded. “Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy” is the first major exhibition to showcase and document the distrust, suspicion, or disgust that artists have manifested toward their contemporary psycho-political contexts. It unveils the underbelly of postwar history, positing supernatural, capitalistic, religious, occult, racial, political, and irrational motives behind historic injustices and dramas. The exhibition doesn’t celebrate conspiracy as an art form, but instead unravels its ecology — its sprawling webs, its fetishized ghosts, and its fascination for haunted architecture — by looking at both sides of the lens: the fantasy and the facts. One side presents different artists’ visceral and subjective responses to the failures of power they’ve witnessed: phantasmagoric (Jim Shaw), symbolic (Cady Noland), abstract (Sue Williams), psychoanalytic (Mike Kelley), traumatic (Sarah Anne Johnson), psychotic (Richard Shaver), ironic (Raymond Pettibon), and frightening (John Miller), among other characteristics. The other side gathers various artists’ more objective responses: analytical (Mark Lombardi), rhetorical (Jenny Holzer), documentary (Hans Haacke), narrative (Alfredo Jaar), revolutionary (Videofreex), and denunciatory (Silence = Death Project). These artworks remind us that mass conspiracy, now thoroughly entangled within modern media, can both undermine and consolidate power, political or otherwise. Without secrets, there is no conspiracy. Without light, there is no shadow, no suspicious dark realm to investigate. Power figures have irreversibly become fertile realms for the most esoteric interpretations. We always look for the truth, or some version of it, even when it’s life-threatening. For some, danger is even the signal of truth. Conspiracy is an asymptote; it bends toward truth without ever reaching it. In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (John Ford, 1962) a reporter says, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” What if, when printing history, we tend to abandon the boring facts in favor of the fascinating but fabricated stories? Welcome to the age of viral and paranoid entertainment.

Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy The Met Breuer / New York

January 11, 2019