The work of Helen Cammock (b. 1970, London) revolves around a specific undertaking: “encouraging the return of the repressed,” to quote Miguel Mellino, referencing Paul Gilroy’s theories on diaspora in The Black Atlantic. The citation is especially relevant to how music is employed by Cammock — as a vehicle to convey a reality that is more problematic than it appears, in addition to acting as a tool to shed light upon the cracks found within the official version of history.

Cammock’s solo exhibition at Void, titled “The Long Note,” is dedicated to the pivotal role of women during the Northern Ireland civil rights movement. The exhibition marks the fiftieth anniversary of what is commonly considered to be the key protest of the movement, which triggered three decades of conflict throughout Northern Ireland, otherwise known as The Troubles. The exhibition title comes from a film commissioned by Void director Mary Cremin, which consists of archival videos taken from television footage and amateur sources, edited together with interviews and footage filmed by the artist, and interspersed with musical interludes and videos such as a performance of “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free” by Nina Simone at Montreux in 1976. What emerges from the film are parallels between the Northern Ireland civil rights movement and other struggles — for example the similarity between the incident in Derry and the “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965 — or comparisons with other events unfolding in Irish society over time, such as the Contraceptive Train on May 22, 1971, and the difficulty for women to be fully engaged in contemporary feminist theory while facing basic issues of civil rights.

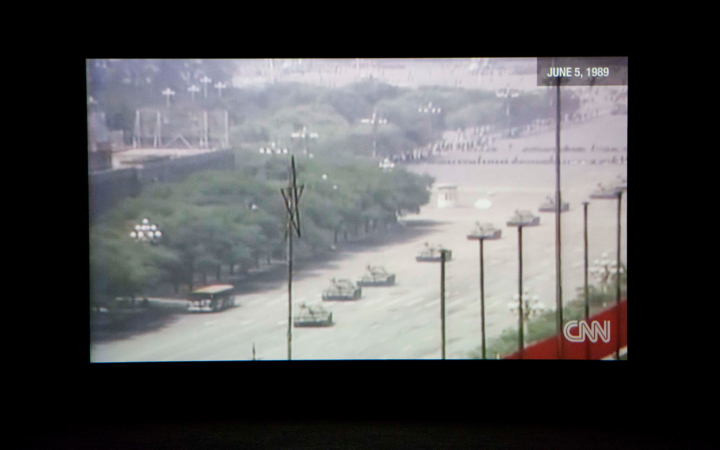

The march as a form of continuous contestation is the theme of the second film on view, Shouting in Whispers (2017), in which Cammock layers videos found on the internet of various protests, from 1968 until today, together with her own documentation. This frontal and nonlinear approach is also found in a series of prints with the same title as the film, in which portions of text are placed upon backgrounds of solid color, almost like warnings that remain imprinted upon the minds of their readers. Indeed, the necessity to read is made evident by the decision to create a reading room dedicated to the history of Northern Ireland and the role of women. However, it is the voice of narrator and Irish civil rights spokesperson Bernadette Devlin McAliskey, as well as the physicality of Nina Simone’s singing, that continue to echo and transport the viewer to a place of collective lament — which was, by no coincidence, the subject of Cammock’s research during her recent residency in Italy as the winner of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women.