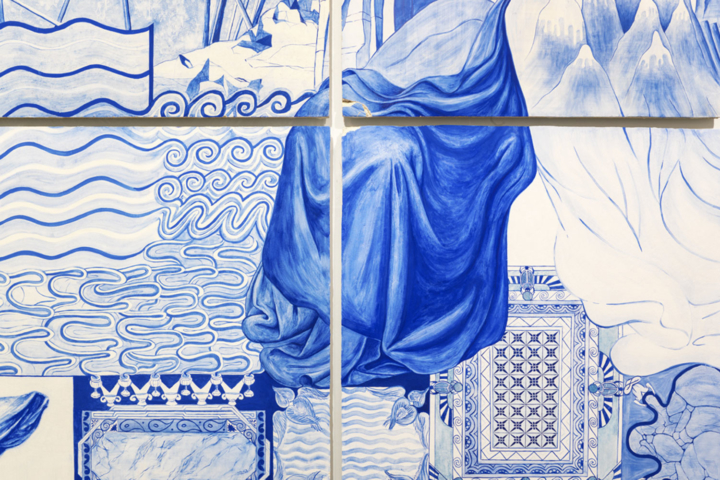

Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s first US solo museum exhibition culminates in an immense blue fresco that subsumes the New Museum’s lobby gallery. Its title, The Place of Stone, is the English translation of Sar-i Sang, the settlement where lapis lazuli is abundantly mined in Afghanistan — a gem trade that has, in recent years, been exposed as a central source of the Taliban’s funding. An atlas of syncretic images painted in blue pigments, Çavuşoğlu’s fresco entangles histories of lapis lazuli with the fraught endurance of the color blue’s cultural value.

Few, if any, contemporary artists work in the medium of fresco. Prevalent globally from antiquity through the renaissance, frescos were produced by painting colored pigments into wet plaster walls, physically sealing the materiality of color into its architectural support. Çavuşoğlu’s revival of this antiquated technique in relation to lapis is doubly significant. Not only was the treasured stone used in frescos as the blue pigment par excellence of sacred depiction, but the fresco’s permanent fixing of color also serves as a material metaphor for the persistence of blue as a cross-cultural imaginary — of the earthly and cosmic, the divine and infinite, as well as the democratic, diplomatic, and less excitingly, the corporate.

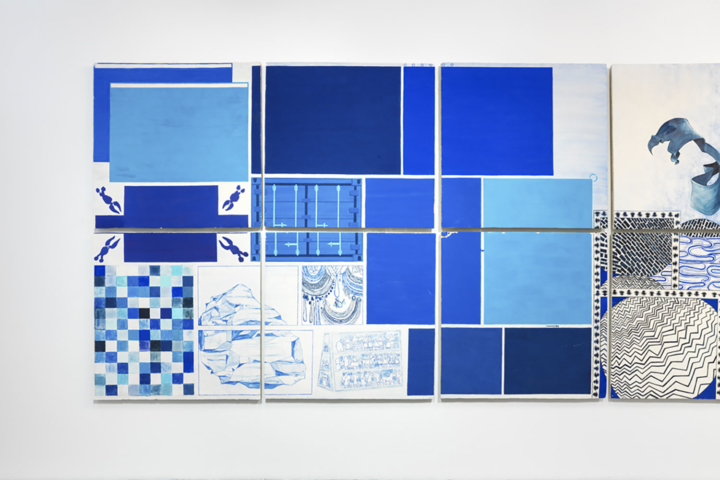

The Place of Stone is most effective in its conjoining of monumental scale with micro-historical moments in the story of a color. Its vast size is an analogy of the sweeping histories it works to recover. An array of symbols related to lapis and blue populate the fresco’s spatial and temporal expanse: a snow-capped Afghan mountain borders Egyptian scarab beetles, and ultramarine decorative ornaments evoke circulations between Islamic, Asian, and European arts. At the fresco’s left end, gridded blue fields conjure the color’s idealization in modernism from Mondrian to Yves Klein to Derek Jarman. On the right, defaced religious icons perhaps gesture to the abject destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban, who continue to profit from the stone’s mining and exchange. Yet the present corruptions are mere instances in a broader history, and as Çavuşoğlu’s fresco visually narrates, there is not one place of stone, but many. Blue does not remain subjected to the aesthetic and political regimes it styled throughout history. Like the people and times whose imagination it captured, it remains open to continual transformation.