Jazz musician and interdisciplinary artist Jason Moran foregrounds collaboration as integral to both music and visual artmaking in his first museum show at the ICA in Boston.

The exhibition’s sculptural assemblages, process-oriented drawings, and co-produced experimental films also propose compelling means for displaying the performing arts within institutions beyond mere audiovisual documentation. It is also a timely constituent of the performing arts gaining notoriety within Boston’s art institutions — including the Tony Conrad retrospective split between the MIT List Visual Arts Center and the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts at Harvard, and choreographer William Forsythe’s exhibition, also on view at the ICA.

The main gallery is filled with Moran’s “sets,” based on storied music venues of varying architectural and historical significance in jazz’s history that have since been razed. Recreated at full-scale within the museum, they house both traditional and self-playing instruments (a player piano, a jukebox), which are also at times activated by live performers. Historicizing jazz’s ephemeral sounds and spaces, the works speak to challenges facing its cultural preservation in the face of continual gentrification, marginalization, iteration, and appropriation. The longue durée of exploited black culture in jazz is alluded to in the use of wax-print fabric, characteristic of pan-African fashion textiles by way of Dutch colonialism, which frames a re-creation of the demolished jazz venue Savoy Ballroom.

The artist’s piano drawings, RUN 6 and Strutter’s Ball (both 2016), for which Moran taped paper over his piano keys and played with charcoal-coated fingers, likewise preserve a sense of ephemerality. The drawings record his musical process rather than a finished product, and suggest a potent absence, in much the same way jazz’s historic influence is here omnipotent yet continually erased. The drawings also reveal the influence of conceptualism on Moran’s own practice, as do his collaborations with artists such as Joan Jonas, Adrian Piper, Theaster Gates, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, and Adam Pendleton.

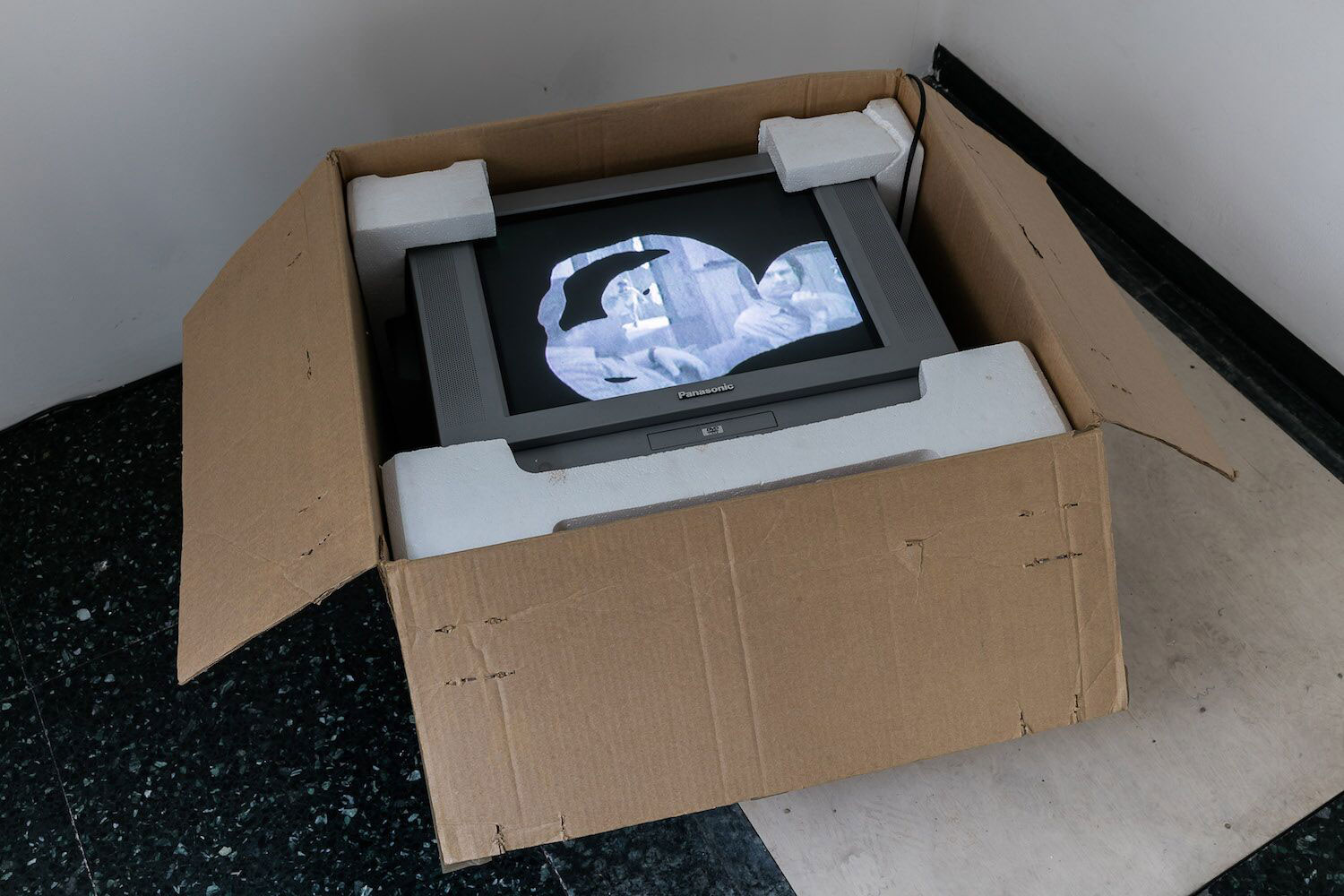

A standout is Moran’s collaboration with Glenn Ligon, The Death of Tom (2008), in which Ligon attempted to re-create a scene from a 1903 film adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, wherein white actors performed the characters in blackface. It turned out that Ligon’s film camera had not been properly loaded, and the image he produced was inadvertently ghostly and abstract. It was a welcome accident. Ligon later saw that such racist imagery is refuted through abstraction, not reiteration. Moran provided the film’s moving score, a riff on “Nobody” (1905), which was the signature theme of Bert Williams, a famed vaudeville blackface performer who was himself black. The collaboration succinctly summarizes Moran’s elegant handling of issues regarding preservation and erasure, and, moreover, his noble refusal of the primacy of an artist’s autonomy, often compromised by the effacing of influences through uncredited appropriation rather than collaboration.