Nemo propheta in patria is a saying valid for many, but not for Vietnamese-born Danish artist Danh Vo. His art speaks a language, tonally and thematically, that is very close to the prophet’s ability to evoke historical events through images of great emotional impact, thus influencing collective thinking. Many of Vo’s most famous works are powerful and sibylline, sensual and often subtly uncanny. In Oma Totem (2009), the artist creates a bizarre fetish of immigration by piling the objects donated by social services to his grandmother upon her arrival in Germany; or in Christmas (Rome) (2012–13), the shadows left by religious artifacts on velvet wall-coverings once used in the Vatican’s museums are transformed into a visual memento mori.

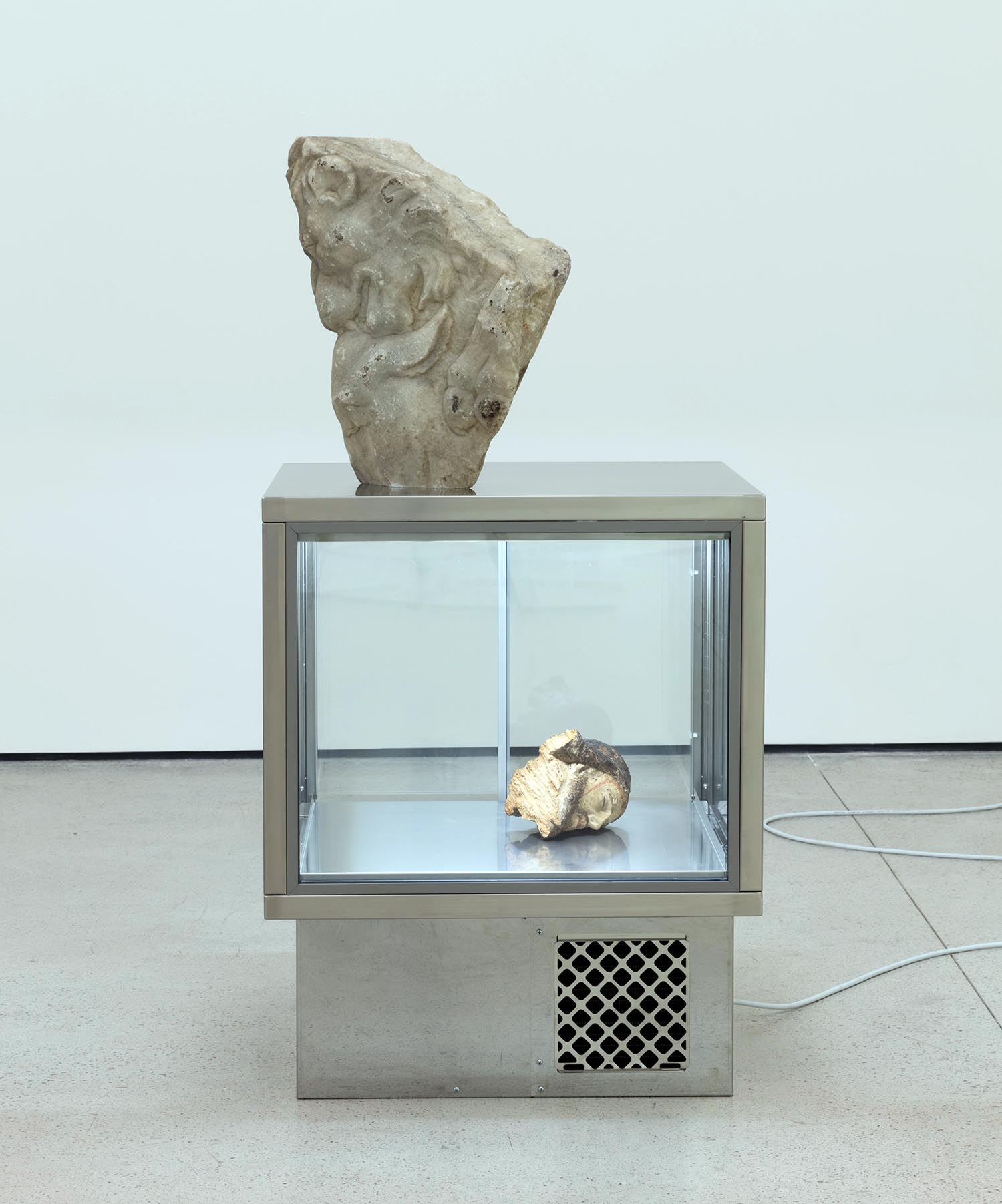

These and several dozen other pieces constitute “Take My Breath Away” — the almost omni-comprehensive survey of Vo’s production that, after being presented at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York last spring, has recently taken over a large part of the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen. The exhibition rightly rejects chronology and focuses on an installation system that underlines the force of Vo’s artistic personality: that of a “borderline archivist” who combines sources and eras with no apparent criteria, mixing highbrow and popular culture with nonchalance, winking at globalism while celebrating the singularity of each story.

But many choices in the show are perplexing. In one of the two exhibition rooms, the storage shelves take the archival note a bit too literally, and the spotlights create a theatrical atmosphere that exaggerates the works’ dramatic charge, depriving them of that cool touch that suits them so well. The exhibition catches its breath in other areas such as the entrance hall and SMK’s Sculpture Street, where Vo displayed the scattered pieces of We the People in 2013; but if on the one hand these in-between spaces are more appropriate for a less inhibited experience of Vo’s art, on the other hand they become a set for a series of ad-hoc collaborative projects that, among other things, see the artist restyling the auditorium’s cushions and redecorating the new cafeteria with plaster statues borrowed from the Royal Cast Collection.

In general, there is a certain anxiety in curating an artist who is very good at curating himself, and this does nothing but provide him with opportunities to broaden his brand of “serial appropriator.” The impression is that everything Danh Vo touches becomes gold; but as we know from the myth of King Midas, this can be a blessing as well as a curse.