When Hauser & Wirth gave Dr. Sophie Berrebi free reign to curate a monographic Jean Dubuffet exhibition in their Zurich gallery, the urban city became a vehicle: its systems, networks, forms, and inhabitants. Instead of adhering to a chronological organization of the artist’s work, wherein gallery rooms would be sectioned into decades, Berrebi moves with carte blanche. Fifty-five major works on loan from museums, private collections, and the Dubuffet Foundation exemplify the discourse of blurred lines between such institutions, such that the academic achievement of the show often becomes exhaustive, rendering unclear which works are for sale.

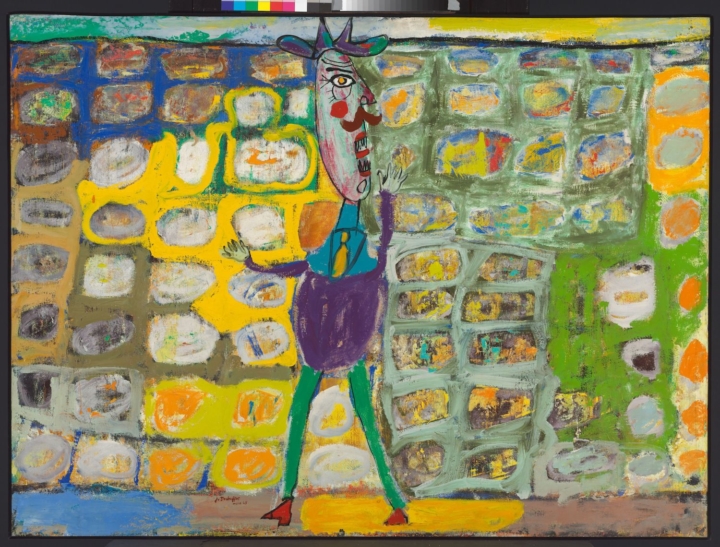

Divided into three stages of Paris’s twentieth-century urban development, or Dubuffet’s categorizable interpretations of the city, the works on show in the first room are from the rarely shown, hardly documented Rhéteur au mur period (Orator at the Wall, c. 1945). In Petit Huleur (Little Howler, 1944), the newsboy’s disoriented eyes and downcast blues and yellows are reminiscent of Picasso’s blue period. The first selection of works features individuals distinguished by their blue-collar role within society — drab pedestrians, an orator, and Le Citadin (The City Dweller, 1974), which Berrebi notes appeals to younger palates for its thick lines and street-art squiggles.

It isn’t until the second section that the urban imagination lets loose. Identity and individuality are lost amid massive Parisian crowds in which faces are unrecognizable, and acrylics take center stage in a nonconformist appeal to the city. “Deskilling” becomes more evident as scribbles spiral across the canvases. In two works both titled Affluence (1961 and 1967), we see distinct faces in a crowd in the first, which in the second iteration become anonymous in the graffiti-like forms of Dubuffet’s “Hourloupe” cycle. The third and final section explores architectural figures — Dubuffet’s desire to advance beyond a salient role in the urban dialogue.

Dubuffet’s Paris is a harsh one. The bourgeois reign seems more postwar than under Haussmann’s renovation of the city in the 1850s, and distinguishes working-class roles into caveman-like figures with blank eyes. Dubuffet is synonymous with Art Brut (or Outsider Art), the term he coined himself in the 1940s to refer to art created without any formal education — welcoming the poor, unwell, and uneducated into the realm of artmaking. While urbanization is very much present, Berrebi emphasizes that the role of the city is not necessarily about figurative representation, or how many rues show up in the titles of works, but rather about using the city as a visual medium for Dubuffet’s thought process and practice. Art Brut is unimaginable without a thriving city, so to exclude Paris in any attempt to understand it and its transgressive energy is futile, and some might say a study on the city’s mid-century pandemonium through the lens of Dubuffet was long overdue. I would be remiss not to mention that it was Switzerland, not France, to whom Dubuffet would voluntarily donate some five thousand of his works, now recognized as the Collection de l’Art Brut.

Berrebi’s interpretation and guided visit is very much sociological, a highly researched tour through postwar Paris that would have urban planning enthusiasts in awe. On occasion of the show, Berrebi published an extensive publication on Dubuffet titled Dubuffet and the City (Hauser & Wirth Publishers, 2018). It is recommended reading.