It was only a matter of time until we got our Harald Szeemann show. In 2011 the Getty Research Institute announced the acquisition of the archives of the auratic Swiss curator — tens of thousands of books and photographs, boxes of papers, correspondence, and ephemera — the single largest collection to enter the institution’s vast holdings.

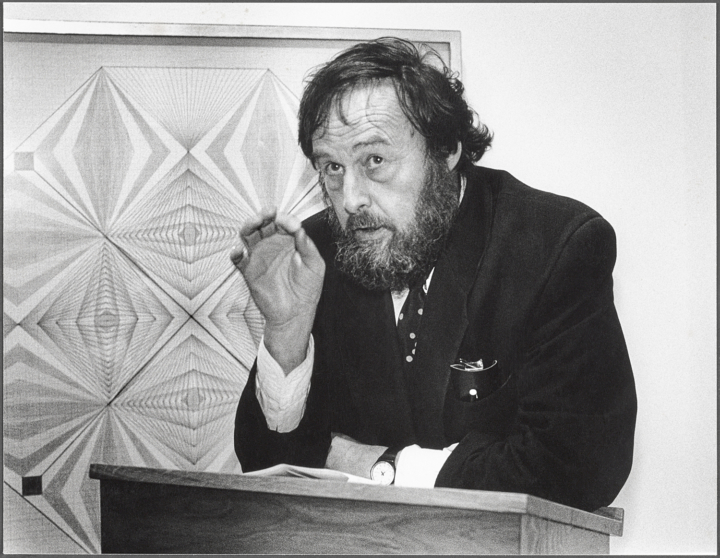

The material had filled a former factory in the Alpine valley village of Maggia, out of which Szeemann had worked from the mid-1980s, coming and going on an endless international itinerary, curatorial journeys that marked, among other things, the emergence of the vaunted globalization of art. Freewheeling and wild-haired, Szeemann cuts an iconoclastic figure — a man possessed of distinctive, sometimes eccentric, tastes, the prototype of the independent curator, a term that in his case seems to carry an ideological sense. But his boxes, now arrived in the hills of Brentwood, would be subjected to the kind of rigorous cataloguing and historicizing for which J. Paul Getty’s well-endowed center is known.

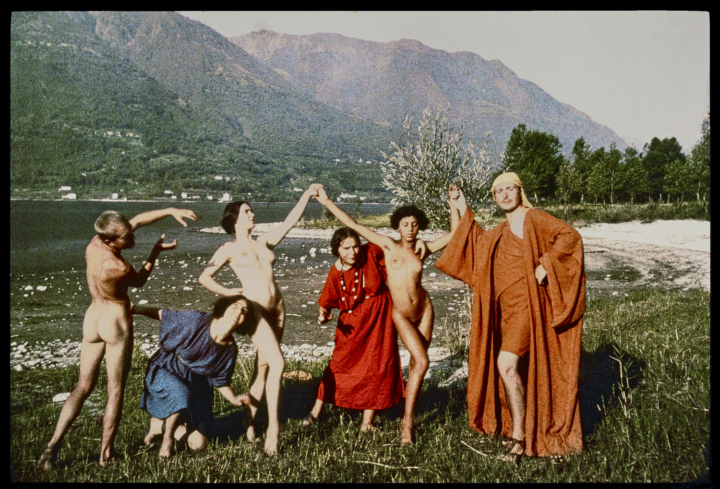

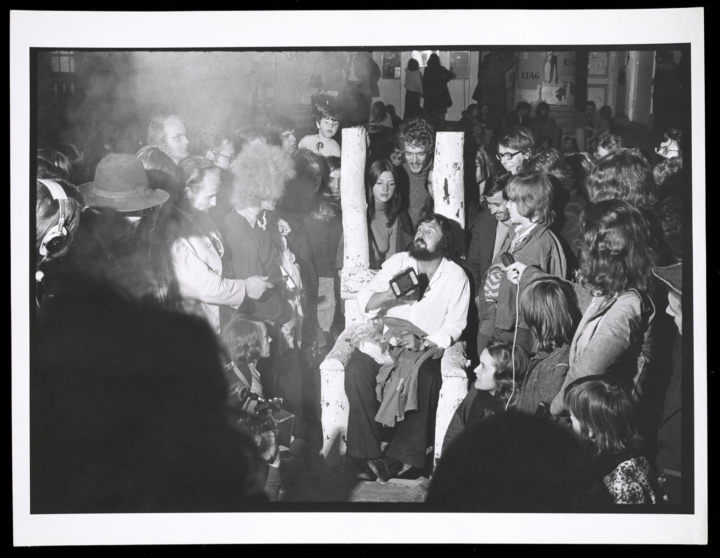

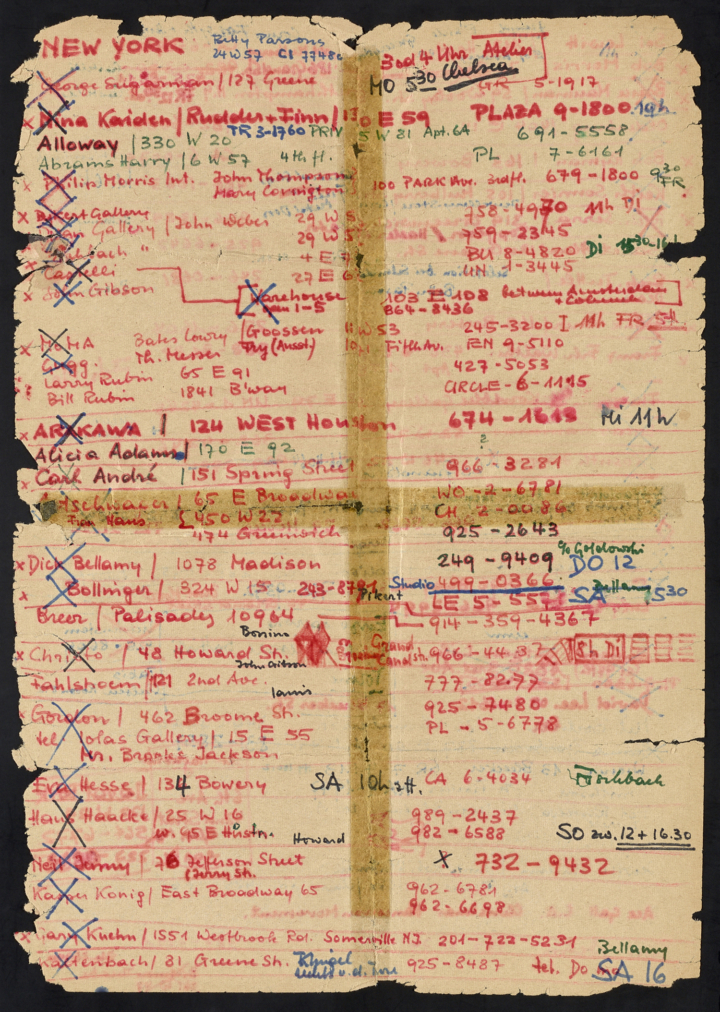

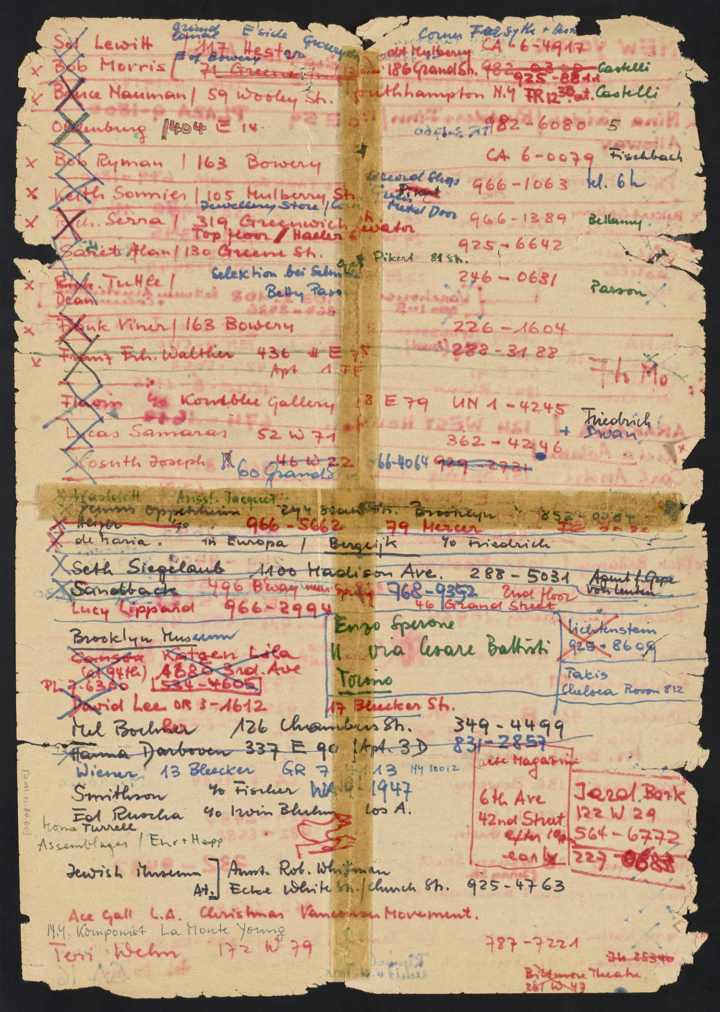

In this, the curators of “Harald Szeemann: Museum of Obsessions” have not disappointed. The viewer gets a thorough survey of Szeemann’s life and career, structured around noteworthy exhibitions and illustrated with documentation, artifacts, letters, and notes. The first section, “Avant-Gardes,” covers his intimate engagement and extensive promotion of the advanced art of the 1960s and ’70s: post-Minimalism, performance, Arte Povera, and conceptualism, inter alia. This takes us from his tenure at Kunsthalle Bern in the 1960s, and the epochal 1969 exhibition “Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form” — a platform for process-oriented art and an exercise in the museum as studio — through his resignation following the controversy that greeted the show and his early freelancing under the ironic aegis of the Agentur für Geistige Gastarbeit (Agency for Intellectual Guest Labor), including “Happening & Fluxus” (1970, Kölnischer Kunstverein) and documenta 5 (1972), with its sections devoted to socialist realism, art of the mentally ill, and science fiction in addition to time-based works and performances. “Utopias and Visionaries” covers Szeemann’s turn toward minor histories of modernism, coinciding with his move to Maggia in the mid-1970s, mounting shows like “The Bachelor Machines” (1975), “Monte Verità: The Breasts of Truth” (1978), and “Gesamtkunstwerk: European Utopias since 1800” (1983), which looked at outsider figures, fantasies, and communitarian communities. The final section, “Geographies,” charts Szeemann’s global circuit in the 1990s and early 2000s, helming biennials in Europe and Asia and regionally and nationally oriented surveys of Switzerland, Austria, the Balkans, and Belgium.

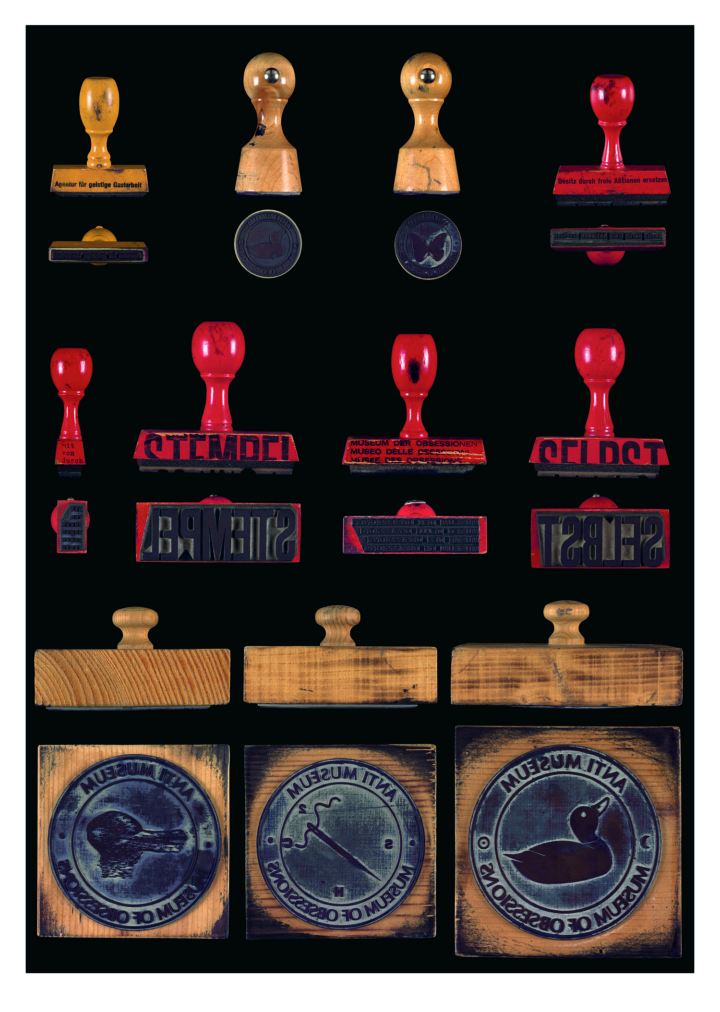

Staging an exhibition about someone staging exhibitions can’t but emphasize distances and contrasts. Wandering the “Museum of Obsessions,” we see just how thoroughly assimilated, how common, Szeemann’s obsessions have become: the now canonical movements of the 1960s and ’70s, revisions of modernism and minor histories, the figure of the globetrotting curator-as-artist or as-celebrity. Rich in detail and informative wall texts, the Getty’s presentation best evokes Szeemann himself in certain key artifacts: a display of a set of stamps with the name and mottoes of the Agentur für Geistige Gastarbeit and a massive collection of airline bag tags, stuck together and suspended from above, give a sense of the combination of humor and self-mythologizing he brought to the task of exhibition-making.

Across town, in the so-called Arts District, the ICA LA presented a satellite show, a restaging of “Grandfather: A Pioneer Like Us,” for which Szeemann exhibited some 1,200 objects that had belonged to his grandfather, a barber, in the curator’s Bern apartment in 1974. What you make of this restaging depends a lot on how compelling you find Szeemann’s mythmaking. While the broadening of the purview of museum display was a vital project, undertaken by numerous curators in the 1960s and ’70s, “Grandfather” rests equally on personal fascination. And it’s exactly the kind of show that, if done today, I would find grating. This might, in fact, be the upshot of the question of Szeemann’s legacy and the banalization of the most radical aspects of his career: he gave birth to the New Curator but left her little opportunity for the kind of iconoclasm he practiced. She can still amass those bag tags though.