Sabrina Tarasoff: Before I ask you about your process, can you introduce the subjects of your recent exhibition “Showcaller” at the Kölnischer Kunstverein? Nudes, cityscapes, flies, nipples in chains: Where do they find family resemblances?

Talia Chetrit: I suppose it is possible to divide this show into three parts which are seemingly in contrast to each other. The aesthetics and approach are very different, but the work is unified by its relationship to privacy.

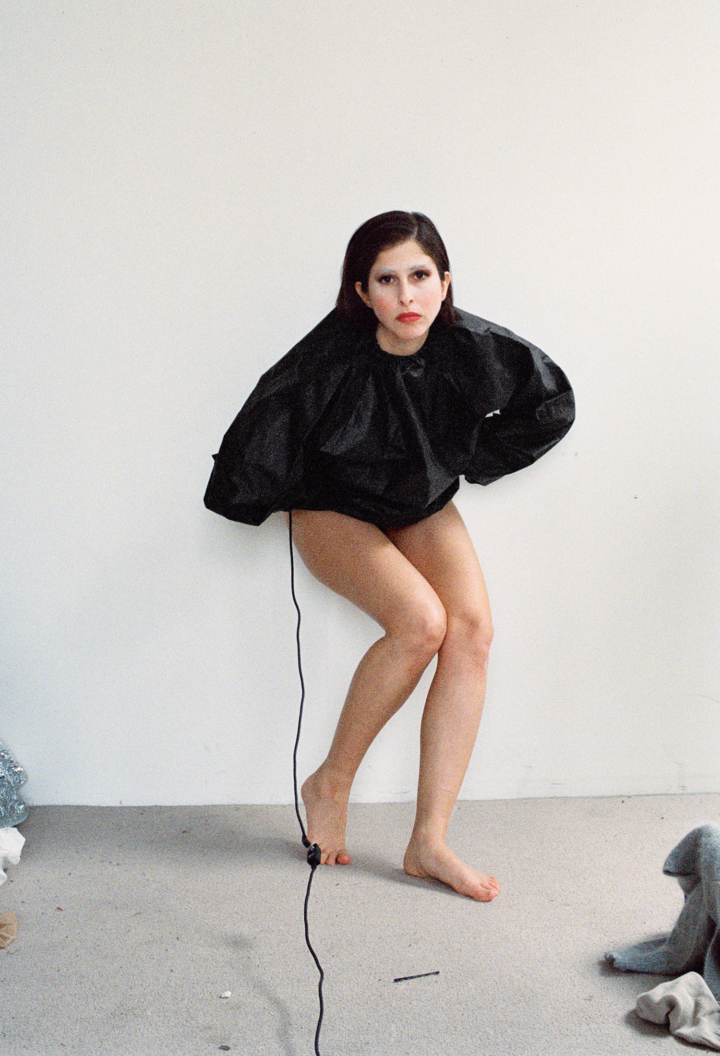

The Streets (2015–ongoing) photographs were all taken from tall buildings in New York City and were shot through glass windows using a long lens. These numerous layers of interruptions between the camera and the many subjects who walk the city below almost abstract the images. No one is aware that I’m taking their picture, and everyone remains fairly anonymous. I like to think that I’m both respecting and invading privacy in a single image. In the Sex (2016–ongoing) pictures, I am documenting my partner and I having sex in a picturesque, natural landscape. I am tethered to the camera by a long and visible cable release. There is a sense that the viewer is implicated in the act. The third part is a more loosely grouped set of black-and-white images of intimate moments, for example Fly on Body (2012), which captures the fleeting moment of contact when a fly lands on skin.

The sex pictures, the street photographs, and the small black and whites are very different types of work, but once they are positioned together, I hope that one is compelled to consider the dynamics of permission and intimacy. In doing so a triangulation begins between the body of work, the action of photographing, and the people observing the work. By positioning and contextualizing these bodies of work together, in close physical proximity, the process and specific intentions of each are called into question.

ST: Your last exhibition at Sies + Höke in Düsseldorf, “POSER,” repurposed photographs you had taken in your early teens, circa 1994–97. These portraits of yourself and your close friends hold some lackadaisical center, the centrifuge of adolescence I guess, around which other more recent photographs orbit. Bearing in mind that ours is a generation beholden to the soft idling of Sofia Coppola films, the Instagram aesthetic of girlish listlessness, all that diluted Edie Sedgwick-esque sadness idolizing the diabolical school of girlhood, we could probably talk a lot about girlhood and its co-optation in social media, how that relates to your image-making… But let’s start from here: How has your process and relationships to your subjects changed since you first started taking photographs?

TC: Of course, the way I think about images has changed, but the process and relationships to my subjects have not really changed at all. This similarity was articulated in “POSER,” where images I had taken in middle school and high school were combined with three recent self-portraits. My interest in reactivating the early pictures was to examine a teenage understanding of the representation of sexuality and an adult’s projection onto those same images. For the new pictures, I invited Corey Tippin, a prominent makeup artist within the New York scene in the 1970s, and we tried out a series of ideas together. As it turned out, this was not unlike the way my girlfriends and I had dressed up for the photographs taken in my teenage years. These images are a consciously constructed interpretation of self-image in front of a camera, in one case as a teenager and in the other as an adult. The intent, the references, and the relationship to ourselves — psychologically — and our bodies — physically — have evolved, but the dressing up and the posing remain similar. To have taken images from my archive and placed them into an exhibition twenty years later is a distinctive act that is as much a subject of the exhibition as the pictures themselves. At the time, those images were never going to be seen, but today those pictures would have immediately been publicly shared, and are an example of, as you say, the “Instagram aesthetic of girlish listlessness.”

ST: Where does failure come into this? In an Interview feature, you’re quoted saying that you considered your first exhibition a failure, and that it changed your thinking. Perhaps because much of your vocabulary overlaps with avant-garde photography and its formal elegance, your work often feels very calculated and finished. For example, “POSER” seemed to locate spaces (or faces) of intimacy in your youth and carry them into the present for reevaluation, which in itself might be considered as a reevaluation of what intimacy meant then and what it means now — as an affect, need, coping mechanism, fantasy, or something entirely else. There is so much margin for error in that, so much psychological murkiness. Does thinking about failure — such as past works that didn’t pan out as planned, or more to the point, photography’s inevitable shortcomings — help guide you through these spaces?

TC: In the Interview article you are referring to, I was speaking specifically of how I felt about my first exhibition, which was about ten years ago.

But, failure in the sense of vulnerability is something I seek to achieve. Sometimes imperfection is symbolic of vulnerability, and those intentional or unintentional flaws add dimension. For example, in the Murder (1997–2017) pictures that I took in high school, which were also included in “POSER,” I staged different murder scenarios with my friend. At the time I was experimenting with the boundaries of fictions, but what I like about them today is how flawed they actually are. In most of the pictures, my friend’s tightly laced-up boot appears to have been thrown off her foot. At the time I didn’t see this flaw, but I now see that mistake as a metaphor for the predatory situations that girls are forced to try and understand at a young age. I also allow for and encourage flaws in my work. I refer to the temporal aspects of the performance for the camera by showing clothing imprints and bra lines and often keeping the debris, like the clothing that was taken off and the equipment, in the edges of the frame. As you mentioned, these “failures” break down the fictions that are built in to the medium itself. There is a never-ending dialogue between fiction and the photograph as evidence.

ST: This feels closely related to problems that arise within the biographical format. As a writer, when stuck with the messy shape of a life and the slipperiness of writing, doubt can be entertained through speculation — through various accounts, through literary devices, even through the spaces of silence that come from subjects who are either dead or reluctant to share. What can be known about a subject, and what kind of meaning we can tease out from them, their expressions, are a difficult thing to convey in an image — and seems to motivate your practice. Photographing your family, covertly, or your friends; revisiting old materials; even in photographing yourself having sex with your partner. Biographers will often pursue their subjects because they are, in some aspect, unknowable to them. How does the “unknowable” within your subjects, or the impossibility of ever really knowing someone, inform your thinking about form?

TC: I agree that a subject is not knowable through a lens. But the presence of the camera both creates and reveals vulnerabilities in my subject (which is sometimes me), which can give access to understanding.

Sometimes it’s about setting up a situation in which my relationship with my subject is challenged in order to incorporate the camera. For example, in the sex pictures, I asked my then-new partner if he would be willing to participate. In some ways this was an attempt to challenge him and provoke an involvement in and a relationship to my work. There was also nothing at stake at the time, because these pictures could have never actually been shown to anyone. With that in mind, we were more engaged with the shoots as a performance between us and the camera.

The presence of the camera itself can also reveal an unknown side of the subject. An example of that dynamic occurred during a photo shoot with my parents. During the shoot, their interaction inspired me to videotape them without their knowledge. I only started taking the video because the photo shoot elicited a flirtation between them that I had not been a part of before. In Parents (2014), my dad is seen kissing my mother’s neck as she coyly asks: “Aren’t you glad I showered?” By revealing on video these in-between moments, when we were negotiating the pictures, I was able to capture a glimpse of the insecurities and shifting power dynamics that are inherent to being both in front of and behind the camera. In this particular instance, the parent/child dynamic was further complicated by the reversal of power.

ST: Of your 2015 show at Sies + Höke, “I’m Selecting,” Art Writing Daily described your portraits as “l’origine du monde-selfies,” which is a nifty way to account for how sexuality in your work happens through convergences between historical and present considerations of self-image. In many of the earlier works, like Crotch (2012), a triangular shape of pubic hair photographed as a sort of geometrical composition, or even in later works like Untitled (Bottomless) (2015), in which your legs act as framing devices for splintered images, sexuality seems implied through an abstraction of form. There is a noticeable difference between the work from 2011/12, which was more fragmentary, composed, and clearly “experimental,” and your current work, which is in a way more fluid and tactile. Can you talk a bit about this? Is it only a formal change, a shift in interest, or also a shift in your thinking about sexuality? Or just what modern womanhood is?

TC: I appreciate that you were looking so closely to notice this shift. Power dynamics, agency, sexuality, and the psychology behind imagery have always been an important part of my work. Earlier I was signaling to and questioning the history of photography and Surrealism as a way to start the conversation. Over the last six years or so, I have found that using the specificity of my own life — experiences, body, family, partners — is a way for me to challenge far more. I am continually reacting to my own work, to shows and to the sequencing of the shows; and trying to build upon, expand, and undermine ideas already laid out in my work.

ST: That leads me to another category of your work: the Celine, Acne, Helmut Lang… With an aesthetic surface that seems to so easily seep into the mainstream, how do you complicate, disrupt, or think through a commercial lens vis-à-vis your artistic practice? It seems really difficult to know what photography is supposed to do these days when the distinction between private and public is so uniquely murky, and image management and self-branding have become full-time jobs for some. I wonder, for example, what it would mean to slap brand logos onto some of the photographs in “Showcaller”: How would they change? Could Streets #4 (2018) function just as well as a menswear ad for the nouveau business casual guy? Or Untitled (Outdoor Sex #1) (2018) act as a sequence in the new Natalie Portman “Miss Dior” ads? I’m not saying this to offend or be facetious, but to consider what happens to an image — and how easily — when it slips between what T.J. Clark has called “notions of virtuality and visuality?”

TC: There’s very little that separates an Instagram photo from an ad campaign from an artwork when the image is looked at on its surface level and in isolation. With a logo slapped on top, most images could function as a more-or-less successful ad. A commercial photo is an offer of sale and is a collaboration between a photographer, a client, a stylist, etc., to manage or massage a viewer’s perception of a brand. There is a directness and transparency about this that I appreciate. An ad is an end point or conclusion. An image for an exhibition is a starting point and is seen within a particular context, surrounded by a curated collection of other images, to hopefully begin a dialogue and encourage a viewer to delve into their own perceptions of the work.

ST: What about power’s relationship to intimacy? “Showcaller” might designate a lack —maybe reverie? — through its hazy distances. But your claim to authority over the images, the reminders of our complicity in their construction, make me think less about how photography as a medium works through those tensions, and more about how intimacy is forged and constructed through similar tensions. This may be returning to my first questions, full cycle — but what do you think? If we are to assume that a part of your pursuit in photography is to forge or construct intimacy, then to what end?

TC: Yes, this is full circle. That exhibition was titled “Showcaller” as a theatrical reference. A showcaller is the person who calls out cues, someone in an authoritative position but who ultimately is not in control. In this case, it was meant to point towards the performative aspects of the works in the exhibition. I consider this to be a good title for my work as a whole. The constructed situations and performances are controlled and staged for the camera, but so much of what then transpires can be seen as metaphorical and echoes current human experience. Conversations about overexposure and privacy arise; we are complicit in the permission to look, to analyze sexuality and to project our personal and cultural biases onto an image. With the pace in which the world of images is changing, it is important to critically unpack and analyze how things are evolving and what the evolution means.