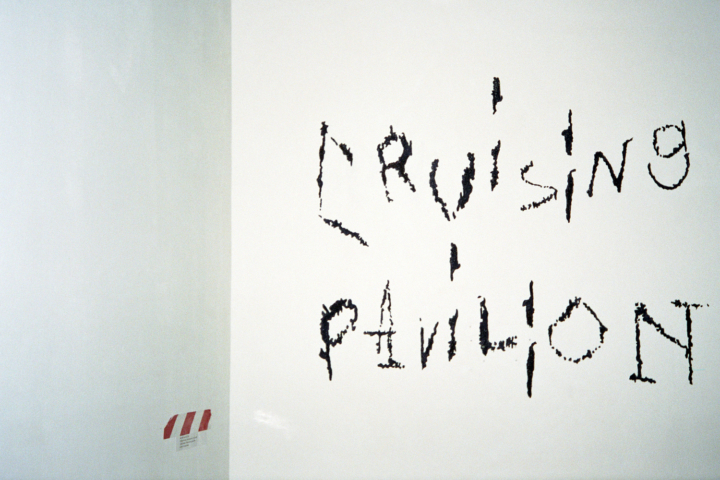

The inaugural Cruising Pavilion sits an additional boat ride away from the main happenings of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, and a canal down from the notorious Garden of Eden cruising ground, visited by Rainer Maria Rilke, Henry James, Marcel Proust, and Jean Cocteau between the Belle Époque and Second World War.

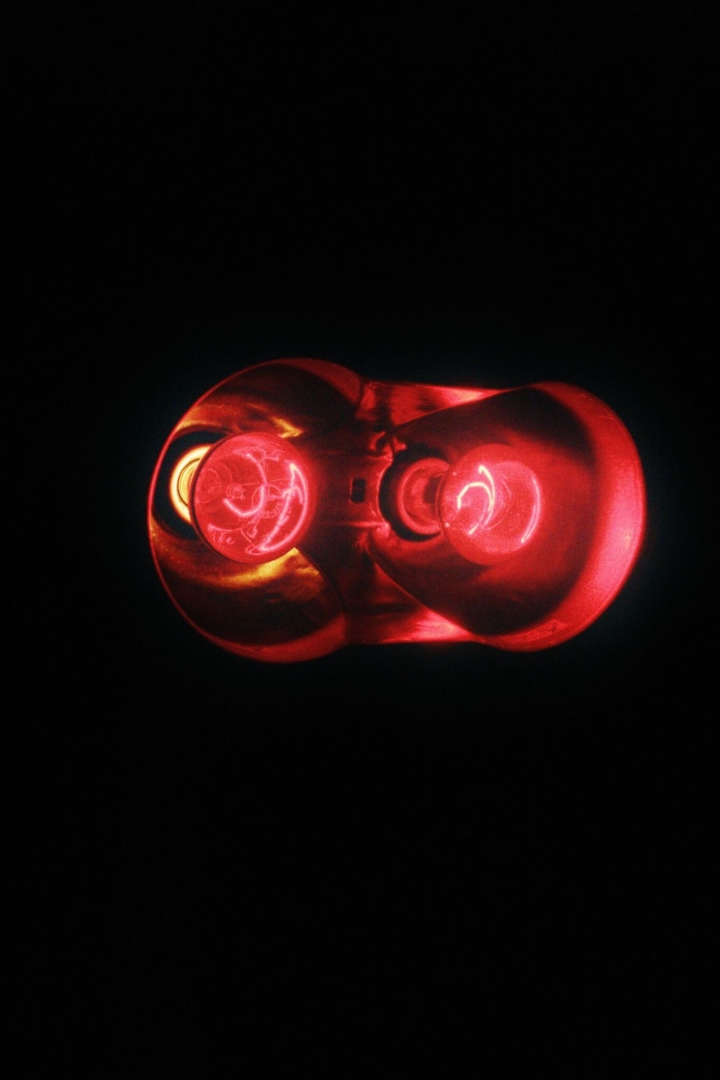

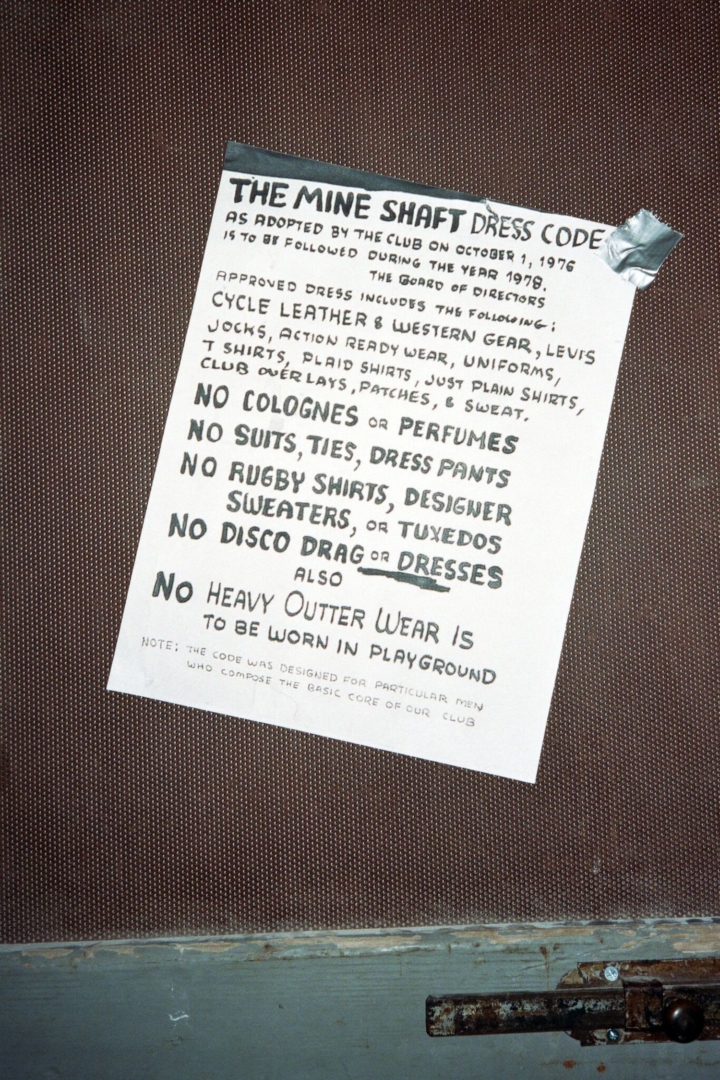

What architectural considerations make for ample cruising conditions? The repurposing of neglected spaces proposed by Studio Karhard’s Boiler Club Extension (2015) elaborates on the traditional vernacular of ’70s and ’80s cruising and urban gay cultural tropes with brushed metal, pipes, factory lights, and bricks conveyed in plans and photographs. Trevor Yeung’s infrared heat lamp, Dark Sun (twins) (2018), and eucalyptus oil humidifier, The Helping Hand (2018), charge the display with sauna-level sensuality and the same dim red lighting that permeates the entire pavilion. Popper diffusers intoxicate visitors as they weave through chicken wire and peep-holed walls before arriving in the garden.

Wooden slats enable voyeurism and frame two narrow, three-story wooden structures within the Spazio Punch warehouse, remnants of Egill Sæbjörnsson’s troll installation for the Icelandic Pavilion of the Venice Biennale in 2017. Visitors crack and tread between the two structures, stepping on throw-downs, “used” condoms, and silk scarves in Lili Reynaud Dewar’s piece: My Epidemic (a series of scarves printed with texts on prophylaxis, sex, love and vulnerability) (2015). Upstairs, Ian Wooldridge’s three urinal supports, shooting with a shallow depth of field three ways: serviced / lone stranger / from the suburbs (2018), employ cock ring–like enclosures to turn normally invisible bathroom infrastructure into caricatured fetish objects.

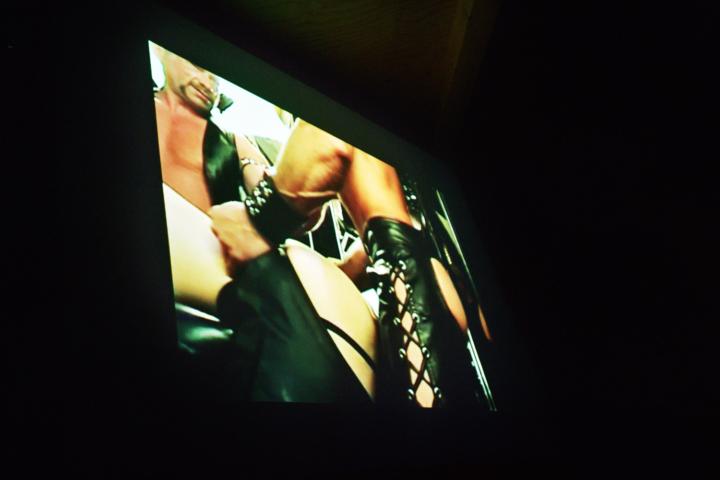

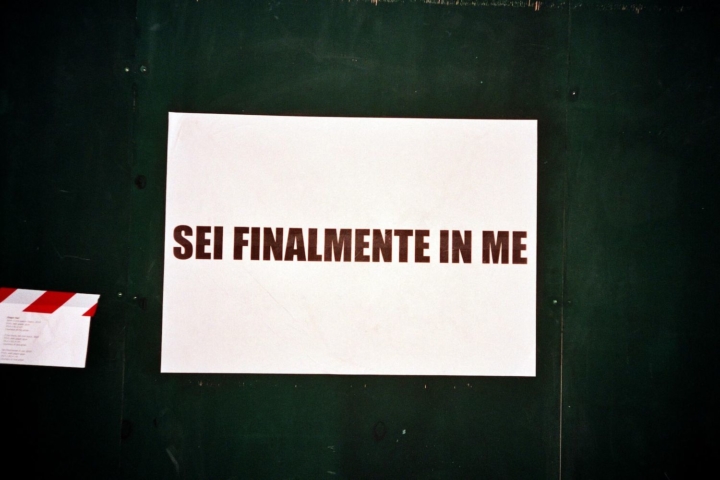

Gym mats and a blow-up mattress emulating something close to my current bedroom interior recall the noxious resources commonly found in dark rooms and sex clubs, colloquialized by DYKE_ON’s 2017 apparel collection, which seeks to set street semiotics of lesbian culture with slogans like “Make dykes great again.” A projected mash up of Le navire Night (1979) refines the leap from phone relationship to physical meet-up, which explodes in Dawson’s 20-Load Weekend (2004), the famous pornographic portrayal of bareback sex after the AIDS crisis, an emancipation from LGBTI+ collective trauma and stigmatization.

It might be too reductive to characterize the architectural traits of a good cruising zone with labyrinths, nooks, curvatures, glory holes, and red lights without considering its intrinsic socio-political history. Beyond the aestheticization of cruising culture, here meticulous, one is lead to question the need for sexual discretion to begin with. If homosexuality is entering the same social strata as heterosexuality, why are spatial conclusions about the future of cruising being drawn from its oppressive past? The space enables visitors to co-exist surrounded by inextricably erotic subtext without feeling any obligation to actually cruise or subvert its inherent guilt, enhancing collectivity in a way that seemed refreshingly post-Grindr. Cruising has its own desirable framework for spatial arrangement, but darkness and privacy are still measures taken to escape violence and persecution in some countries, and not simply characteristics of what might render cruising so deviantly pleasurable for others.