Young architects seeking to work against architecture’s stagnancy seem to be more engaged with producing exhibitions and publications than buildings. Most clients rarely venture into the risky, experimental side of architecture and the profession seems sclerosed by its own past heroes and bypassed global techno-corporate systems.

If this is a rather common observation, at least the Milan-based architecture office Armature Globale is trying to tackle the issue head-on. Founded and directed by architect and curator Luigi Alberto Cippini in 2016, the practice is committed to remedying architecture’s malaise by “forgetting radicality and focusing on aggression,” as its founder says. Its design methodology is to openly adopt conflict, violence, force, and assault in the production of buildings, in direct opposition to those architects who typically deploy their creativity in resistance to architecture’s inherent violence and the surrounding forces of capitalism — often to the point of being in denial of their own inescapable complicity. It is essential to understand this unique position in order to appreciate the work of Armature Globale, which tends to be as ambitious and obscure as the reality it wishes to expose.

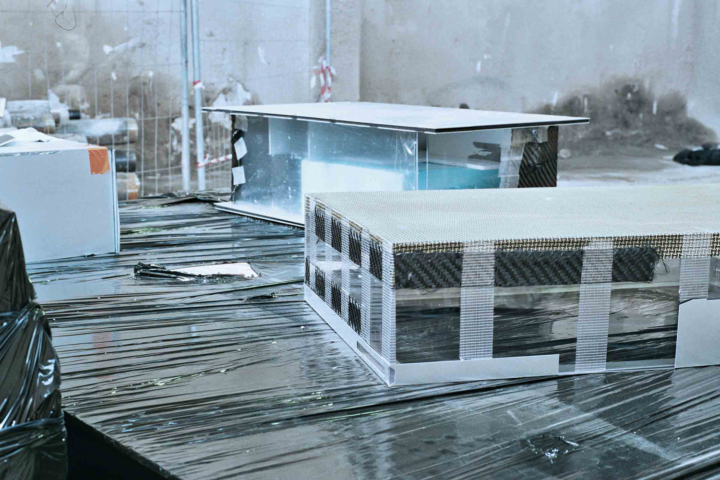

Their latest exhibition, “Unapt Environments,” took place over two days at the end of March in Milan, inside the active construction site of an old chemical paint factory that was in the process of being decontaminated, a few streets away from Fondazione Prada. The show was installed in a large rectangular room exposed to the outside with bare concrete walls, floors, and ceilings. Inside, placed between three hydraulic pile-driver trucks, four architecture models, a series of posters with computer-generated images and portraits, and an exhibition publication were the sole means of unpacking the show’s divergent themes.

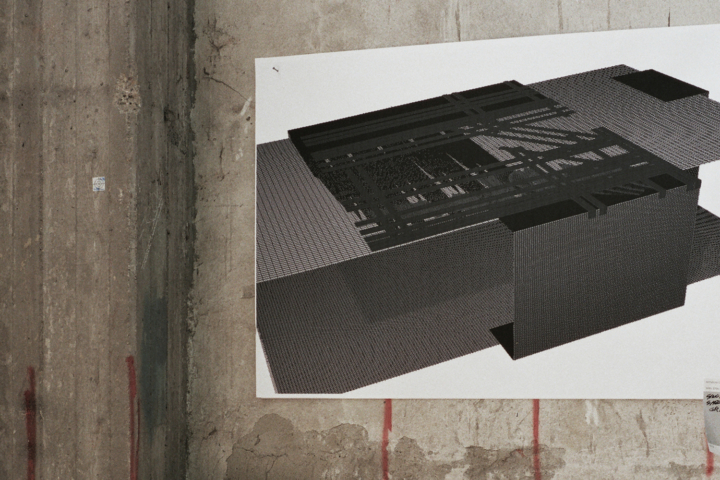

The two smaller models were precarious assemblages of composite plastics, glass pieces, Kevlar, and carbon-fiber fabrics haphazardly taped together. The other two were 250kg stress models, more appealing and recognizable as the skeleton of a building. Each of the four were developed by Armature Globale with engineering firms DDR and GR10K, as prototypes and proof-of-concept models for a hyper-safe, hyper-structural system for their current commissions. The posters on the walls were all images of either computer screens showing pixelated screenshots of 3-D models inside BIM (Building Information Modeling) software applications or flash photographs of dirty screens through which viewers could discern the black-and-white portraits of four dead twentieth-century architects: Otto Ernst Schweizer, Walter Christaller, Jean Dubuisson, and Xavier Arsène-Henry. This cryptic combination of elements in an already dark and hostile construction site culminated in a catalogue written in a dense strikethrough font, which contained a series of texts by various authors on the models on display and the lives of the figures in the portraits, including a novella titled Eurothriller, set in Swedish energy producer Vatenfall’s administration center in Hamburg City Nord.

“Unapt Environments” is frustratingly indigestible on purpose, which is what makes it worthy of interest. Armature Globale dives deep into the illegible technics of modern power to better reveal their inhuman and deadly grammar. Everything is reframed as part of a totalizing techno-fascistic project: the most important architects of the last century didn’t design buildings, but construction systems that laid the foundation for today’s BIM software, responsible for the erosion of the superficial pseudo-humanism that persists in architecture.

Armature Globale dares to look into the ruthless logic of new construction processes by showing them raw, unedited, and freed from their veneer. And, rather expectedly, the results flirt with an ambiguity that makes their politicization unclear. In fact, at no point does Armature Globale convey any intention or hope that the prevailing power in question can or should be countered, channeled, or bypassed, instead remaining suspiciously silent on the political motives behind their fetish. Are they advancing or resisting a crypto-fascist agenda? Exposing architectural processes is certainly an incisive first step toward intent, but the second needs to be an architectural exploit.

This being said, the work of Armature Globale is still in early stages of development, raising more questions than answers; but their dynamism and aggression must be duly praised for refreshing the discourse of architecture and, hopefully soon, its practice.