What did I bring back from my visit to this exhibition? Most probably the memory of falling asleep three times, and spending four hours in the show while struggling to keep my experience within the realm of the conscious. If this sounds like the most boring exhibition ever, that is quite a mistake.

The lure into the show was a film projection, Maybe this act, this work, this thing (2017), focusing on two dancers who appeared to be improvising on stage, as if developing a choreography as a composition of movements reminiscent of the mechanics of machinery. Occasionally they make sounds: breathing, hissing at each other or whispering conspiratorially, creating a sense of intimacy that is interrupted by the stomping of feet and sudden, swift movements of the body, like in the abrupt drama of tango. The lush costumes and close framing of the camera, mainly on the dancers’ faces, gives the piece a nineteenth-century feel not devoid of eroticism. It’s as if the dancers were trying to get in touch with their innermost workings through a process of physical introspection.

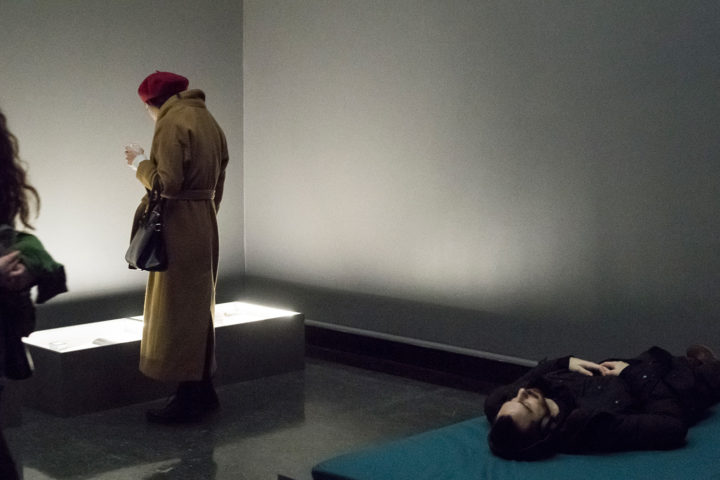

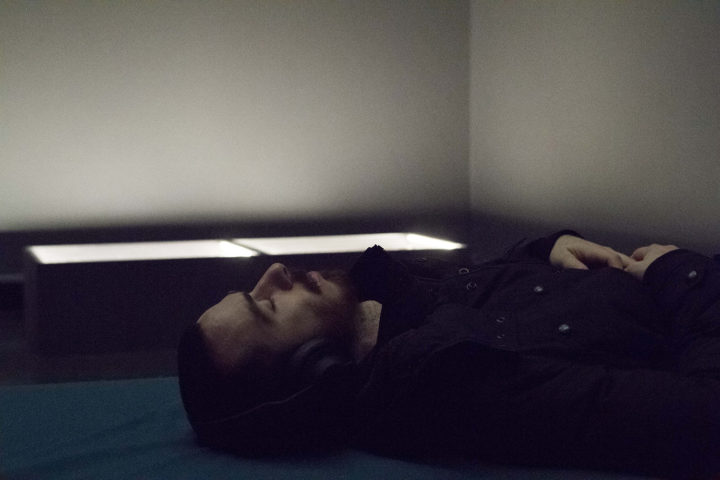

In this sense, the title can be read as “bringing something back” from a journey into the human body, not only as a physical site but also as a reflection and inventory of cultural and biological history. This can be experienced on three meditation platforms on which viewers can rest and listen to three different audio tracks, which develop a kind of suction effect this reviewer found irresistible. The darkened rooms may have contributed, as well as the consistent rattle of the film projectors behind partition walls, which divide the large spaces into more intimate areas. Lying down and putting on a headset, after listening to the introductory prompts — counting backwards or moving through your body from the outer extremities to the core — I fell asleep. Waking up after an intense moment of disorientation, I listened to the whole track again, which maneuvered me through many trap doors until I finally arrived at my very own Department of Abandoned Futures (2015), deep inside my individual imagination, my hopes and fears, thereby echoing the dancers’ attempts at introspection.

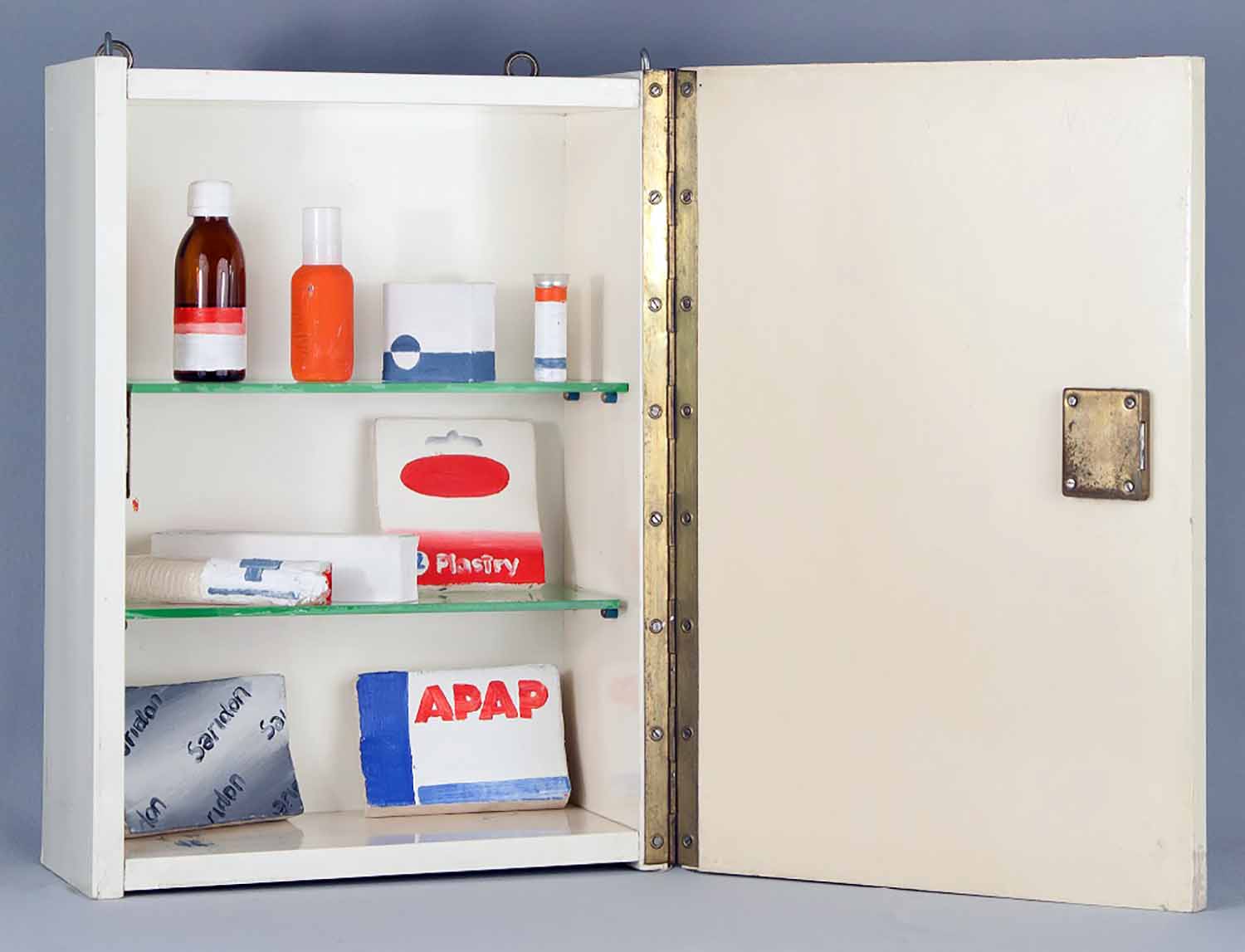

The experience, somewhere between the conscious and the subconscious, is intense, puzzling, and deeply personal. The films and meditation tracks are augmented by a beautiful display of additional material, books and objects that form less an illumination but an illustration of the experiences and ideas this show facilitates — a disparate library, where classics like William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch sit next to a salt crystal, a book on Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, and a book by Jakob von Uexküll, who established the scientific research field of biosemiotics, the reading of the world of nature as a system of signs. The problem with von Uexküll is his latent and public anti-Semitism, which stands in stark contrast with his otherwise visionary ideas. It may sound pedantic, but failing to find a way to address this particular aspect in an exhibition that, in its particular way, deals with the human body as a vessel of history is not only inconsistent but seriously problematic, because it connects this particular state of being half awake and easily influenced with the workings of propaganda. And the historic anti-Semitism of the cultural elite is more than a footnote in history — after an intense experience, it left me wondering, wide awake, but with a bitter aftertaste.