Curated for the first time by two artists, Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, the fifteenth Istanbul Biennial may surprise those who expected a radical project — one grounded in the theatrical and humorous approach to institutional critique that has characterized the duo’s most accomplished interventions since the mid-1990s, such as opening a fake Prada store in the desert outside Marfa (Prada Marfa, 2005), or the staging of a play in which the actors are all notable twentieth-century sculptures (Drama Queens, 2007).

That is precisely the direction that Elmgreen & Dragset’s previous curatorial endeavors have followed: engaged to work on the Danish and Nordic pavilions at the 2009 Venice Biennale, the two transformed them into perfectly reconstructed domestic spaces, orchestrating, with their very recognizable imprint, the participation of another twenty-three artists and designers, each one of whom contributed to the hyperrealist mise-en-scène.

In Istanbul, instead, the duo have opted for a lighter touch: the exhibition is free of curatorial tricks, of a rigid and programmatic layout; it is spare, sincere, unburdened by theoretical superstructures. Even to a fault.

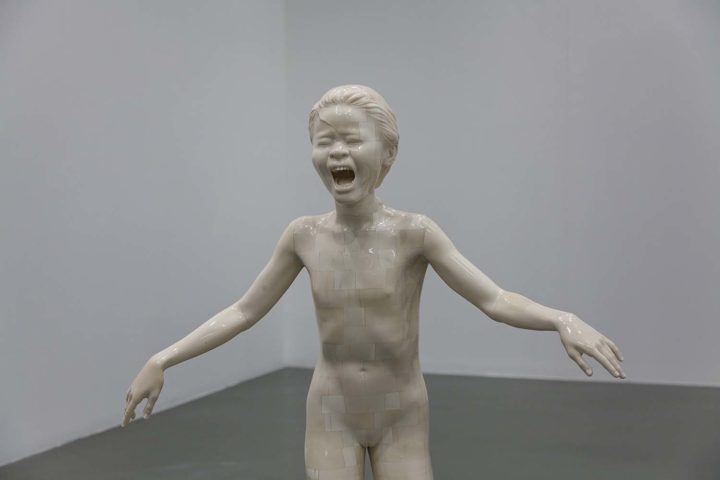

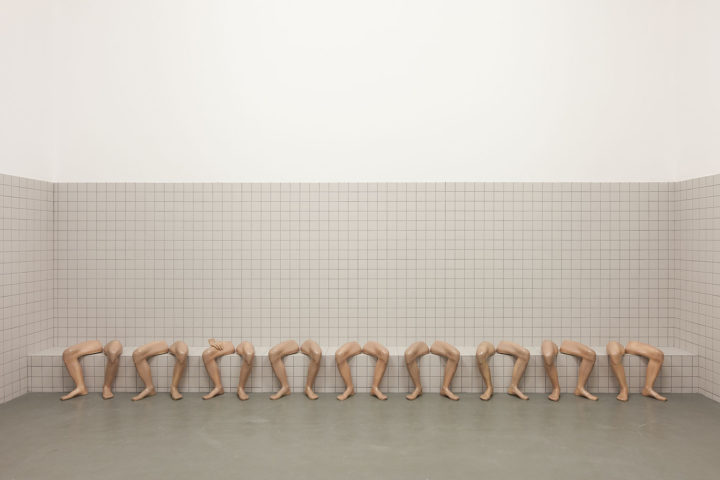

Grouped under the title “a good neighbour” — suggesting themes of home and proximity but also cohabitation, privacy and fear of the other — are works by fifty-six artists, thirty of which are new productions. Unlike the previous Biennial curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, which was spread across the city, including various hard-to-reach places, this edition is restricted to only six neighboring locations and can be visited without any particular exertion, taking one’s time with the works.

Some of these are notable: a mural by Latifa Echakhch, featuring the figures of protesters (reminiscent of Gezi Park’s demonstrators), that appears as though already corroded by time, on the verge of fading away; an installation by Lydia Ourahmane, with a live trumpet solo performed on the concrete frame structure of a house under construction, as a commentary on the environmental and social degradation of her native Algeria; a video by Erkan Özgen, showing a deaf-mute boy miming the Siege of Kobanî from which he’s escaped; or Alper Aydin’s installation, in which a bulldozer blade pushes branches and bits of chopped-down tree trunks in the corner of the gallery (another echo of Gezi, and of environmentalism as a metaphor for the struggle for human freedom). Monica Bonvicini’s Hausfrau Swinging, a 1997 video installation, is still incredibly current, especially in a country that is returning to discussions of whether a woman’s place is not in the home, and where domestic violence is on the rise.

Though the works just described might suggest otherwise, the Biennale’s references to Turkey’s current historical and political moment are never overt — a fact for which the curators have been criticized, as they have agreed to work on a large public event (albeit one organized by a private foundation, the IKSV) in a country where freedom of speech is increasingly restricted. In fact, subtle messages of dissent but also hope are disseminated throughout the programming. For example, as Elmgreen & Dragset told, in the choice to show Lee Miller’s photographs taken after the fall of Hitler — already seen at Documenta 13 — or to exhibit works by Liliana Maresca, the Argentinian artist who passed away in 1994, linked to the political events surrounding Argentina’s return to democracy in the 1980s. Pedro Gómez-Egaña’s large installation, which shows a secret, underground life taking place beneath the apparent order and decorum of a bourgeois interior, aptly expresses the state of the cultural scene in today’s Turkey (and wherever freedom is not guaranteed) as well as its determination to continue survive. Yet the most significant reflection prompted by the Biennial is of a universal nature, embedded in the deep wound that our era of walls, exclusions and social divisions has inflicted on the very concept of humanity. Choosing a theme of propinquity, coexistence, closeness, appears in this context like an invitation to take an interest in others, to look at and participate in lives taking place next to but also very far from our own.

A rather stark contrast to this minimalist but empathetic Biennial is offered by the sparkling Contemporary Istanbul fair, which coincided with the days of the Biennial’s opening. The co-presence of the two events, in addition to a healthy program of openings in public and private spaces, signaled that the energy — not least economic — which had made Istanbul one of the most animated cities of the international art scene is anything but extinguished. The fair, this year in its twelfth edition and headed by a new director, the London-based collector and curator Kamiar Maleki, is constantly improving in terms of both presence and quality; nonetheless, it still bears witness to the almost complete scission between the market-driven tastes represented by the fair and the conceptual radicality and aesthetic sophistication that the Biennial has been bringing to the city for thirty years — and that the best Turkish art amply incarnates.