Is Greece a metaphor? Two months after the opening of Documenta 14 in Athens, the Kassel edition followed with the still-unanswered question of what we learn, have learned, are learning from Athens. It figures a lossy, allegorical Greece: a field in which critical narratives about global dispossession, austerity, migration, historical democracy, historical fascism and cultural production might alternately be thought through and acted out.

In a recent interview in art-agenda, former Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis noted the exhibition’s simultaneity with the liquidation of Greek national assets (“fourteen regional airports, extremely lucrative ones as Santorini, Mykonos, and so on”) in a sale to the German-state-owned Fraport. One can imagine that the revenue these airports generate, which previously might have been directed to the Greek public services rendered moribund under austerity, now contribute to the wealth of the German state, whose funds, in turn, have brought Documenta to Athens.

What does it mean for a lender to learn from a debtor? In a 2016 issue of C Magazine (in a text unrelated to the exhibition), Candice Hopkins, one of Documenta 14’s team of curators, considers the relationship between learning and power: “‘Pedagogy’ stems from the Greek, paidagōgos, which denotes ‘a slave who accompanied a child to school.’ Perhaps paidagōgos implies learning from the dispossessed (although clearly those doing the teaching had little choice in the matter).”

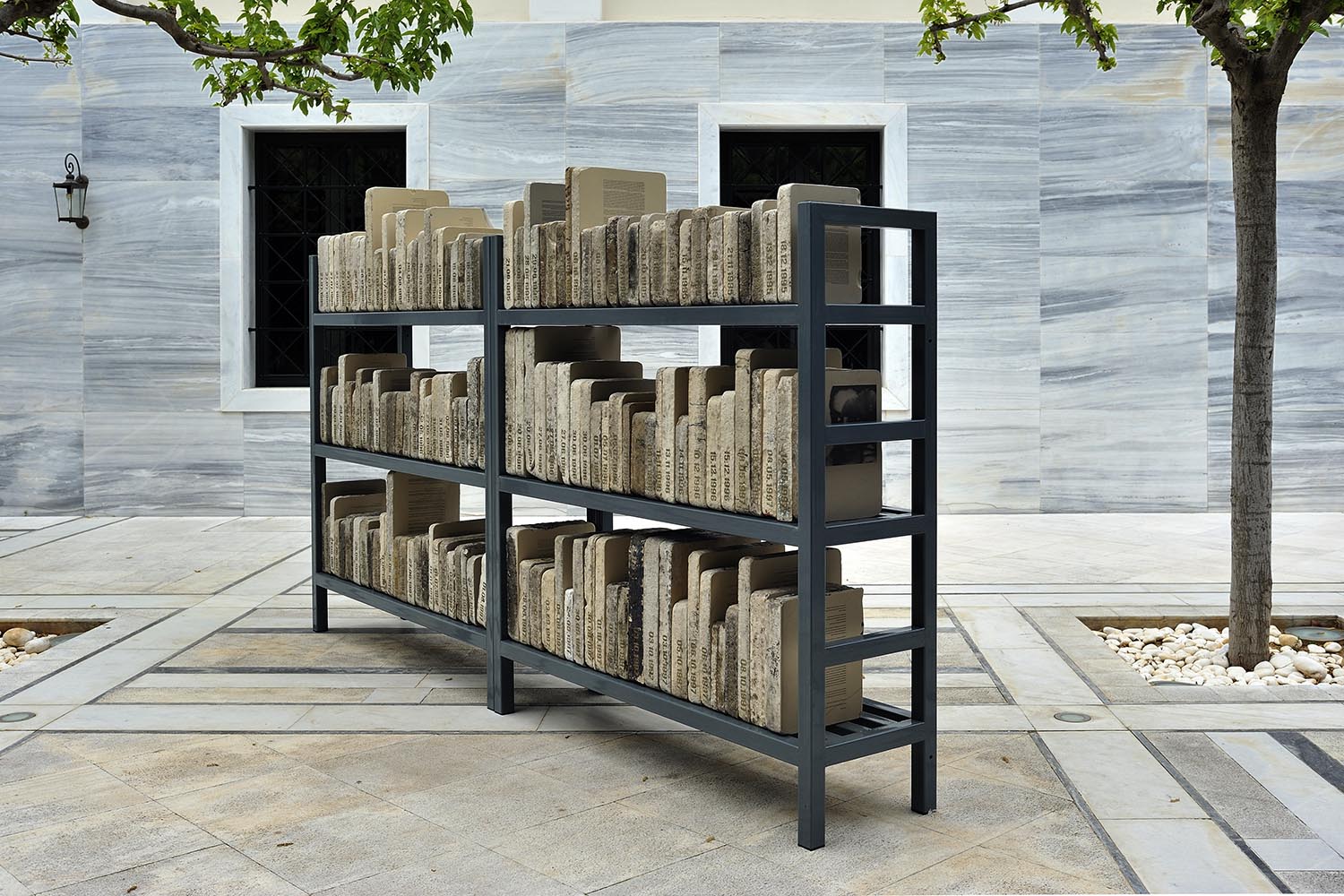

What one expects an exhibition to do — and what collusions with instruments of repressive power one accepts as normal in the name of discourse — likely depends on what one understands an exhibition’s value to be. Some see an inherent value in exhibitions and their making, while others don’t. Documenta 14’s most visually iconic work, Marta Minujín’s Parthenon of Books (2017), is a re-creation of a monumental work originally erected in Buenos Aires in 1983: a to-scale replica of the Parthenon, rendered in metal scaffolding and filled with books. The Buenos Aires version used banned books excavated from the storage of the just-deposed Argentinian military junta; the Kassel version uses books banned in other contexts. Facing it to the north is Banu Cennetoğlu’s BEINGSAFEISSCARY (2017), a text installation whose title replaces the name of the Fridericianum on the building’s facade, reproducing its distinctive lettering; the phrase is borrowed from Athens graffiti. Facing the Parthenon of Books to the south is a temporary Polizei station marked with Documenta signage. Though “being safe is scary” reads, in an art context, as a platitude about the threat of hegemonic culture, the presence of Documenta-branded art cops brought to mind unintended resonances between the repressive state, the politics of public safety, and contemporary art’s structural relationship to the verboten (both real and imagined).

My own learning at Documenta began among the works of Lorenza Böttner, whose paintings, drawings and photographs are presented in the Neue Galerie alongside archival materials documenting the armless transgender artist’s life and practice, which seems to have otherwise had few public presentations following her death in 1994. A framed photograph documents one of Lorenza’s public performances of painting: standing on the sidewalk, she uses her feet to paint a canvas in front of a few onlookers, marrying the aesthetic figuration of the painting with the labor of its making, a political act insofar as the fact of Lorenza’s body itself is political. Other works trade in the malleability of gender and its markers: in a few series of black-and-white portraits, Lorenza’s face and hair are subject to transformations in style, fluidly borrowing from the masculine, the feminine, the elaborate and the peculiar. In a drawing on paper, Lorenza’s body is rendered in two vertical halves, split along the gender binary, with each side styled differently. The central piece in the small installation dedicated to Lorenza’s work is a large painting dated 1985, in which Lorenza, seated, cradles a baby in her lap, feeding it with a bottle she holds in the crook of her neck. Alongside Lorenza’s self-imaging of a disabled, gender-nonconforming body as vital, autonomous, expressive and erotic, this central portrait of the artist as a vision of care and social reproduction reads like the freedom to choose what one’s body means.

Installed in one of the exhibition’s glass pavilions on Kurt-Schumacher-Strasse, Vivian Suter’s Nysiros (Vivian’s Bed) (2016–17) stages hanging sheets of painted, unstretched canvas, a surfeit of colorful, ordinary pleasures. A central wooden bed within the installation is made up with sheets of painted canvas, with additional paintings stacked underneath. Vivian’s Bed reminds me of that of Jean Rhys: the British-Caribbean writer who, near to the end of her life, poor and obscure and sick with alcoholism in the British countryside, lived with what would make up the manuscript to her best-known novel, Wild Sargasso Sea (1966), in a pile under her bed. The image of the genius female invalid — and its attendant fluidity between waking, sleeping and working — is one that forgoes the preciousness (and the implicit gendered and classed stratifications) of distancing cultural production from the domestic and that, for all its other sadnesses, seems to bear a measure of private freedom.

The possibility of private freedom also figures in Rosalind Nashashibi’s video Vivian’s Garden (2017), of which Vivian Suter herself is the subject. On view in the Naturkundemuseum, it’s a short, affective portrait of Suter and her ninety-five-year-old mother, Elisabeth Wild, and the house they share in Panajachel, Guatemala. Nashashibi catalogues routine intimacies, adjacent to art practice, in the course of Suter and Wild’s days. Suter scratches paint over canvas, carries a framed panel through the jungle. In a wheelchair, Wild makes collages from paper and magazine clippings. They discuss Suter’s former husband: “You changed your life, you got rid of your husband”; “He was scary”; “He changed several times.” Nashashibi soundtracks the video’s end with a pop song, Sébastien Tellier’s L’amour et la violence (2008), and there’s a pleasure in both how incongruously cheesy it is while nonetheless making the story feel big. At Neue Galerie, a room is dedicated to a selection of Wild’s small, framed paper collages — architectural, graphic, poppy and bright.

These moments were, for me, among Documenta’s best. Other works bear mentioning: Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens’s Ecosex Walking Tour, which invited participants to take part in a commitment ceremony to the earth, and to visit the planetary clitoris, conveniently located in Kassel; Pope.L’s Whispering Campaign (2016–17), whose materials are listed as “Nation, people, sentiment, language, time”; Miriam Cahn’s wondrous, violent dreamscape nudes; and Gordon Hookey’s MURRILAND! (2016), a monumental history painting, rich with literary slippages, narrating the violent colonial foundation of the Australian state. It’s difficult to see these works subsumed into a project in which Greece is positioned as a nebulous other, to which anything — and especially any kind of marginalized identity — might be compared. On a bad day I would say that trafficking in inadequate metaphors is not a failure of the art system but rather its most reliable work, of which this year’s Documenta is an ordinary example. From Athens, we might learn that everything is either the same or it is different.