The Museo Reina Sofia’s current exhibition “Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism (1938–1948)” is perfumed with the politics of desire, yielding to an excavation of spirit through the sibylline energies of youth. Founded by Georges Henein, Ramses Younan, Kamel El-Telmissany and Fouad Kamel, the movement’s immersion into the psyche was a libertine effort that blurred the present with thoughts of an untapped future.

Delightful incongruities, fraught with the tipsiness of young adulthood, were used to dissolve the bourgeoisie’s conservative aesthetics and mindless autocracy in solutions similar to Walter Benjamin’s most “excoriated and ridiculed ideas” during his period in the German Youth Movement.

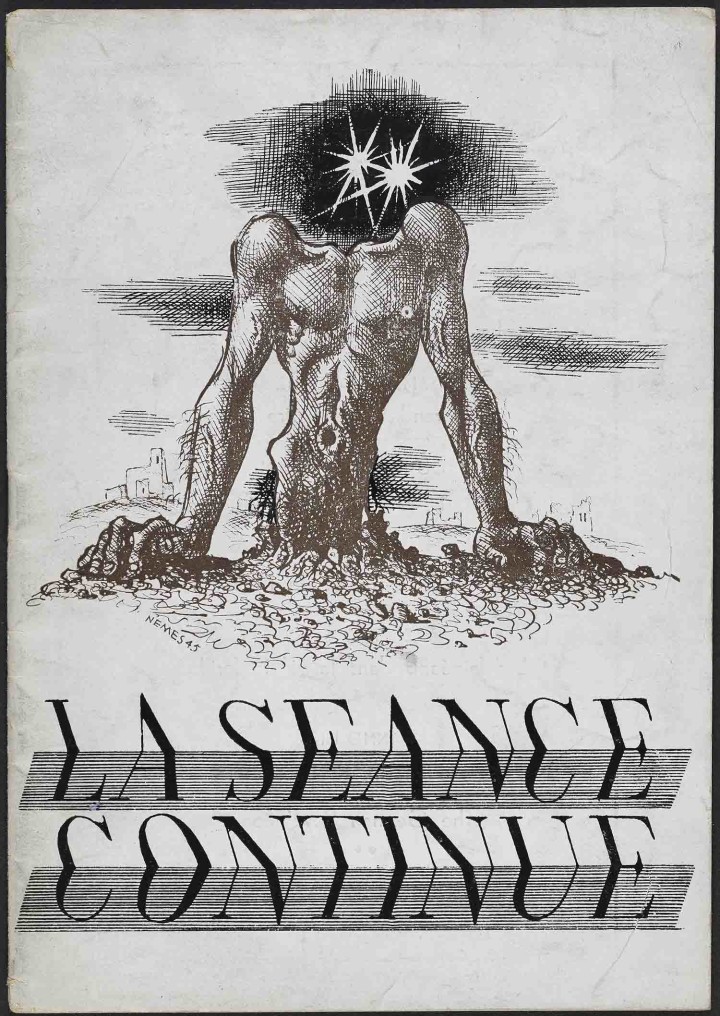

While contemporary conservatives have co-opted the surreal, “Art et Liberté’s” debauched unveiling of its unconscious still has a political charm. To give in to an illogical and unnerving human psyche, with all its pulsions and desires, is to stretch the empty literalism of an oppressive and systematic reality to the breaking point. This is particularly true of Inji Efflatoun’s painting Untitled (1942), wherein female bodies are composed of malleable substances somewhere between muscle and hair. They cohere with Mahmoud Said’s La Femme aux Boucles d’or (1933) in which cleavage takes center stage, the subtle tan line emphasizing a plump command. Reality’s osteoporotic nature fractures, revealing cracked passageways into body, mind and matter. As Robert Rauschenberg noted of his “Early Egyptian” sculptures — his cardboard sarcophagi stacked at zero degrees of surrealism — bodies allow for “a silent discussion of their history exposed by their new shapes.” Such was the caustic psychoanalysis of the Surrealists: an idealistic reform of spirit, and a desire to work through the rubble of war, its waste, through a soft and pliant psyche.