Montreal, 1967: in celebration of the Canadian Centennial, a world’s fair representing sixty-two nations not only blessed the city with a metro system, but also with some related architectural leftovers. Two years later, Mies van der Rohe’s gas station was completed on Nun’s Island.

On September 21, 2016, one month before its official opening, the ninth Montreal Biennale presented its first event, which took place at this very gas station. It consisted of a sound performance by Joseph Namy involving nine passenger cars. While the opening day of Expo 67 at Parc Jean-Drapeau drew a crowd of more than three hundred thousand visitors, Namy’s 2016 piece was shut down early by the police. However, the Biennale’s official and very well attended opening was successfully held at the Musée d’art contemporain one month later. These complex shifts over time are conditioned by what is both inside and outside the city of Montreal, of Quebec, and of Canada.

What is the purpose and meaning of a Eurocentric world’s fair concept in 2016, when a globalized “world” confronts a reconciliation of colonialism amid an impending New Chapter in Quebec’s fastest gentrifying city?

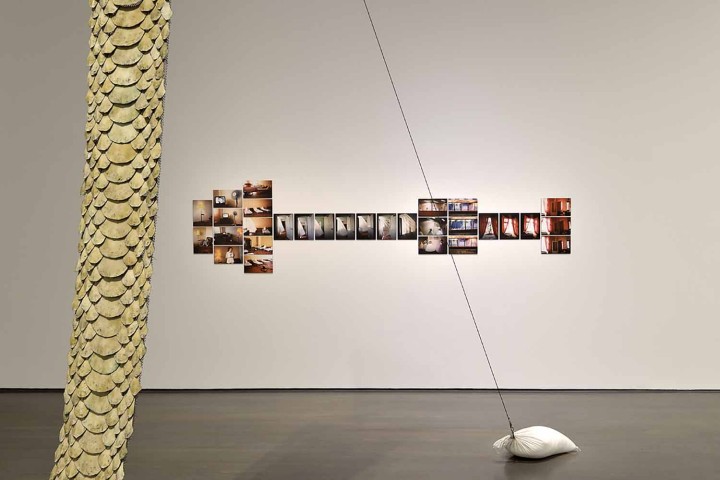

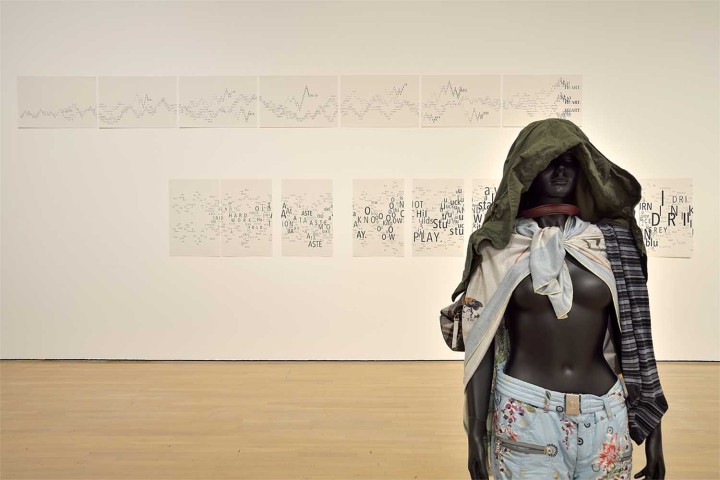

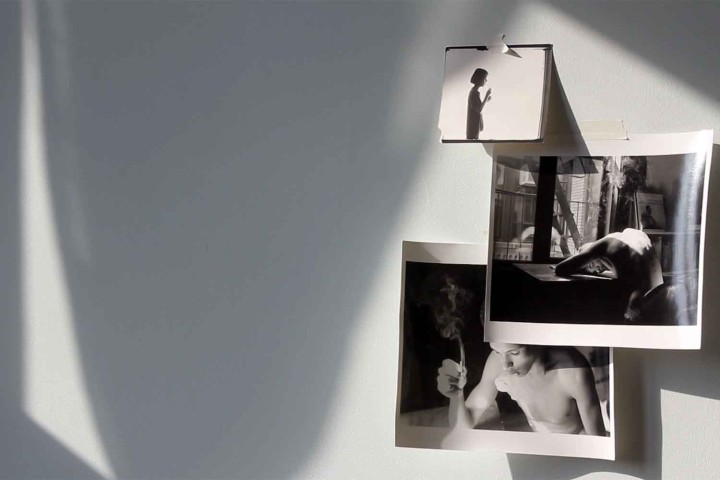

The Montreal Biennale is well aware of the criticality of this question. Tanya Lukin Linklater’s He was a poet and he taught us how to react and to become this poetry Part 2 (2016) and David Lamelas’s The Desert People (1974) are among the strongest responses to what curator Philippe Pirotte in an exhibition tour described as a “perverse situation.” The Biennale then, in reference to Jean Genet’s The Balcony, intends to offer “a place where representation itself can be perversely troubled.” According to the curatorial statement, it is this perversity that resists universalization and instead enables fantasy as the structuring and strictly individual element of encountering things. Within the Biennale’s exhibitions, this perversity is produced by the physical presence and captivity of many of the works on view, including the falcons in Anne Imhof’s fashion “opera” Angst III (2016), appearing not only in Montreal but frequently on Instagram as well. But the piece that most enables the stated idiosyncrasy of art is perhaps Moyra Davey’s Hemlock Forest (2016), an intimate and gloriously spare homage to Chantal Akerman.

What does this encounter look like when it comes to people rather than things? Marina Rosenfeld’s Free Exercise (2016) is a score for an orchestra made up of military and experimental musicians — a large-scale composition for drummers, percussionists, wind players, and others. It was performed at the opening night of the Biennale at the Armoury of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal by Les Fusiliers alongside Philippe Lauzier, Valérie Lacombe, Adam Kinner, Cléo Palacio-Quintin, Jessica Moss, Kristie Ibrahim and Noam Bierstone — luminaries from Montreal’s contemporary and improvised music scenes. This uncannily magic exercise in the limits of tolerance was monitored by the Maisonneuve Infantry’s motto “Bon coeur et bon bras” (Good heart and strong arm). After seventy minutes of drums and trumpets, the sound of a turntable finally appeared like an amplification of silence. Every presence produces an absence. Candice Hopkins helped me understand how, from an Indigenous perspective, a utopia is necessarily also a dystopia. The utopia of the New World was built upon eliminating the world that was there before. There are different concepts of time at work in the present, which cannot simply be subsumed into a timeless “archaic.”

Every presence produces an absence, and every presence needs to be maintained. Corpus Cleaner by the New York–based research and production collective Thirteen Black Cats, on view at Galérie UQAM, is based on a correspondence between Claude Eatherly, the US Air Force pilot whose “all clear” weather report enabled the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, and Günther Anders, a German philosopher and antinuclear activist. When first immigrating to Los Angeles, Anders worked as a movie prop cleaner in the Hollywood Custom Palace. In the correspondence that appears as voice-over in the film, he tries to prevent Eatherly from agreeing to an offer by a Hollywood producer to make a film about his life because he thinks that the Hollywood apparatus will not be able to process the fatal act of the bomb. “The property man knows where everything is,” writes Eatherly to Anders, “but only the cleaner sees it fully.”

Back to the gas station: During her night shift, gas station keeper Y in Knut Åsdam’s film Egress (2013) thriftlessly uses Norwegian oil to wash off the blood stains of a violent fight. The Montreal Biennale 2016 meets its own presence with a self-criticality that keeps the city’s horizons open. Perhaps, in order to allow for encounters to take place outside of itself, it needs to be handed over from “property men” to cleaners.