When it opened in 1844, Reading Gaol was hailed as the pinnacle of prison design. Half a century later, its most famous inmate gave the lie to such a statement. Between 1895 and 1897, the playwright Oscar Wilde was incarcerated for “gross indecency” after details emerged of his affair with Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas.

It was in art that Wilde found solace, and it is for art’s sake that the prison has, for the first time, opened to the public this year. The doors to the claustrophobic cells that line the jail’s long corridors have been thrown open, and artwork and letters leading international artists placed inside. Display cases near the entrance present photos of old inmates, copies of the prison’s ground plan and design elements, and articles about the Victorian penal regime, emphasizing the long history and dark significance of the place.

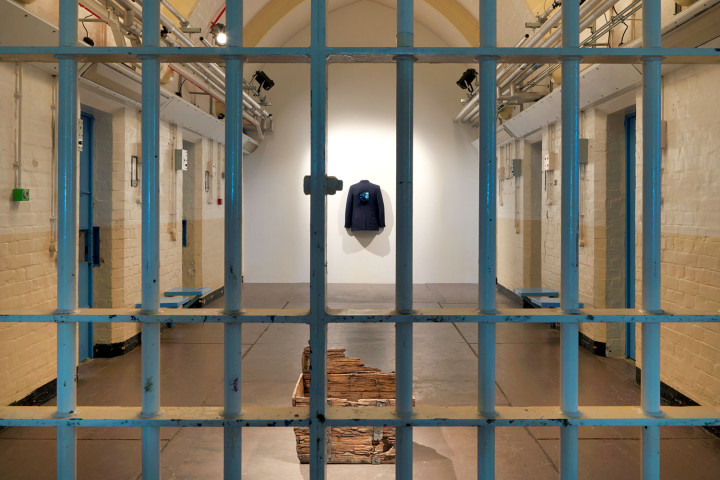

The best artworks respond directly to this context, but the short planning period (Artangel received permission for the project in July) means some artists sent existing pieces, not all of which work. Roni Horn’s annotated photographs of the Thames seem tangential — though they are given a certain symbolic inflection by the presence of Robert Gober’s sculptures nearby. These are embedded into the fabric of the building: one digs into the floor to reveal a woman’s torso, which in turn is prised open to expose a babbling brook; the other consists of a filled-out suit jacket (as anonymous as any prison uniform) disappearing into the wall, with a viewing window in its back revealing another grotto. Here, water becomes a metaphor for an inner life, painfully constrained and yet also offering a means of escape.

Wolfgang Tillmans displays three photographs taken on-site, two showing his own face unsettlingly distorted in a prison mirror, the third depicting the mirror dimly reflecting empty space. They are an eloquent comment on the devastating impact of the Separate System, revealed as nothing less than the forced erasure of the self. Marlene Dumas has painted portraits of Wilde and Bosie: there is something sad and uncomfortable about seeing the two men, whose fates were so tempestuously intertwined yet ultimately so separate, sharing a cell.

And throughout all this, you can wander freely. Some spend hours there, others explore at speed, taking in — in a few minutes — meditations on prison sentences that last and destroy years. You’re free to run or walk, free to stray into disused rooms, free to take pictures. Free, even, to pick up a print by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, of a bird in flight, and take it home. In De Profundis Wilde wrote, “People point to Reading Gaol and say, ‘There is where the artistic life leads a man.’” Artangel has turned that statement and all that it implies briefly on its head.