Absent from Roberto Burle Marx’s monographic exhibition in New York are materializations of what he was known to create: abstract geometrical parks and gardens. Faithful to its title, “Roberto Burle Marx: Brazilian Modernist,” the show adopts a modernist ethos by presenting Marx more as a designer or planner than strictly an architect or artist.

The exhibition’s narration of Marx’s introduction to and fascination with botany retells an old story about nationalist discovery in the Latin American modernist tradition. While Marx was studying painting as an adolescent in the Weimar Republic, he became interested in Brazilian flora after visiting the botanical garden in Berlin, which he compared to Rio de Janeiro’s gardens, in which one could hardly stumble upon a native species. The exhibition presents Marx’s turn to botany as a Brazilian awakening. Its pairing of the paintings Red Mangrove (1963), composed of organic shapes that resemble menorahs, and Still Life with Figa, Amulet and Lace Tablecloth (1933), depicting a giant closed black fist amulet, reveals an internal clash that will eventually be resolved in his landscape designs.

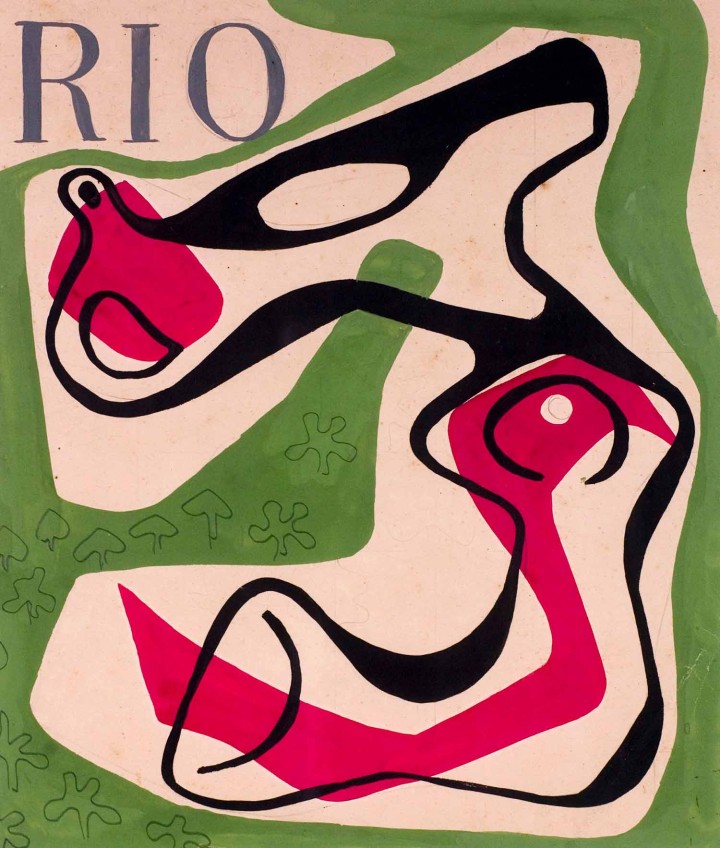

However, by showing plans rather than plants, or by keeping things virtual rather than real, the exhibition avoids the sentimental trap it sets up. Marx not only replanted vegetation in parks and gardens but devised a graphic schema and a new language of lines, curves and colored segments to graft a new visual context onto plants that had been barred from use.

The exhibition also highlights seven artists all born after 1950, among them Juan Araujo, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Nick Mauss, whose work was inspired by or resembles that of Marx. If relationships with his contemporaries were in any way extrinsic to Marx’s work, or might merely be presented as nodes in a network for pedagogical purposes, their absence would be less glaring.

Marx’s originality concerns the fact that his materials were literally uprooted from the soil and consist of physical stuff rather than words and images. The exhibition ultimately offers few tools to engage such an unprecedented practice. In his Brazilian Intelligence (1965), the German critic Max Bense referred to Marx’s gardens as cosmos, the work of an arrangeur whose garniture corrects the “growing disorder of tropical chaos.” This account, while marred by the rhetoric of a writer who continuously exoticized Brazil, at least proffered a hypothesis concerning Marx’s constructivist handling of nature. The extent to which his plans for parks and gardens inflected contemporary theories concerning entropy remains to be found out.