Manifesta 11, the latest edition of the roving European biennial, seeks to explore what makes its current host city, Zurich, tick: work. It’s a reductive idea that the curator, artist Christian Jankowski, has chosen for an exhibition titled “What People Do for Money.”

One assumes the curator knows that people everywhere work to financially survive. Still, the exhibition fetishizes the idea that artists and members of the art world might interact with pedestrian workers. In addition to a large group exhibition, thirty artists were paired with different professionals to shadow and get inspiration for what are labeled “joint ventures.” These projects are mainly spread throughout the city in their real-world locations. A floating fort on Lake Zurich projects a rotation of documentary-style films created from all these interactions. Most of them, anyway.

Georgia Sagri was paired with a banker from Julius Bar and sought to create a double portrait of the situation of host and guest: the banker and herself, as well as herself and Manifesta. Sagri refused to be filmed for documentary purposes without final approval and control — that is, unless she was paid as an actress to play herself. When this was declined, she worked extensively on contract negotiations with Manifesta to ensure that she had complete control of her work, its presentation and her image. These meetings, as opposed to the ones between her and the banker, were filmed as a component to her total project, Documentary of Behavioural Currencies (2016), showing both an interest in and keen ability to challenge institutional systems of power and language. Exhibited at Bank Julius Bar on the tony Bahnhofstrasse, with a duplicate exhibited at the Luma Foundation, is a wood pavilion with a video of herself and the banker duplicating the systems of exchanges that Sagri witnessed while shadowing the banker. The other video, the one showing her negotiations with the biennial, Manifesta refused to exhibit, as well as the finished contracts showing their legal agreement. For this she called upon the local art space Upstate, unofficially completing her project in public and thus undermining the control this citywide institution believed it had over her as an artist and human being. The resulting film is beautiful and revealing, showing ingrained institutional power structures and sexism. The blurred faces and voices of Manifesta employees (at their request) are menacing and sinister, reacting against Sagri’s well-spoken stance to maintain her artistic integrity.

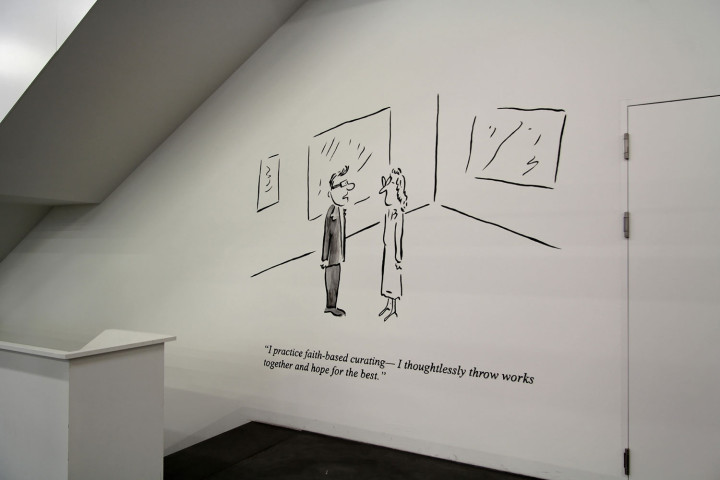

Continuing along this line, the other successful ventures in this sprawling affair are those that go beyond the one-liner of a profession and capture a fleeting human element. Mike Bouchet’s The Zurich Load, in which he worked with a waste management plant to form into cubes a day’s worth of excrement from his host city’s population, isn’t one of them. In a large hall reeking of ammonia, the blocks have been installed in a manner visually akin to the work of Walter De Maria. It’s vintage shock art minus the shock. Pablo Helguera’s blown up Artoons are New Yorker–style comics that fill the public walls of the Lowenbrau art complex. They’re typical art-world jokes that range from the witty to the morally questionable. One shows a museum director introducing an unpaid intern as the new curator, exposing that the line between knowing about a societal problem and taking a stand are worlds apart. Leigh Ledare’s The Here and the Now (Zurich Groups 1:1) is an extensive video installation showing the fruits of a three-day session with the group therapist he was paired with along with twenty-one participants. The video of the final session, in which the entire group is circled together for the first time, is mesmerizing and banal. Given no prodding, the group sits down and awkwardly fidgets and makes small talk. Over time they begin to confront one another and eventually take sides. There are tears, apologies and accusations subtitled in English from Swiss German. Ledare sits in the back, the camera focusing on him occasionally, as he watches, not understanding what is being said. It’s pure human interaction, like a high-brow reality show sans any manipulation, and it is mesmerizing and revealing about more than just these people. We’re all exposed as awkward and aggressive without provocation.

That these basic facts are not exposed further in Manifesta sheds light on why and what people actually do for a paycheck. Like a mask, the jobs we do for money hide us and help us for better or worse. Perhaps the broader failure of the theme is actually its success in connecting to the city of Zurich. Here order and societal responsibility can do nothing but trump any interpersonal stance.