Robert Walser’s prose is attentive to surfaces in a way that is both dedicated and momentary. He misdirects, diverges and floats around the exterior of things to reveal the many beautiful and inscrutable points of connection with their circumstances and surroundings.

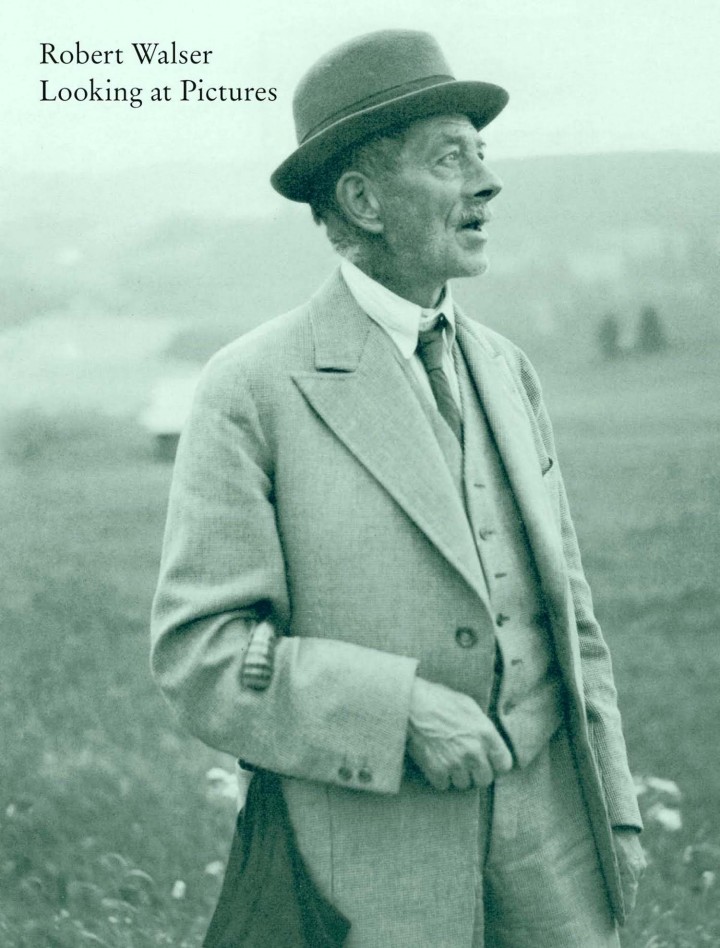

In Looking at Pictures, a new collection of Walser’s writings on art, we are offered a collection of moments in which the German writer turned his distinctive impressionism — in reviews, short prose pieces, invented dialogs, etc. — toward works of art and artists. And under Walser’s scrutiny, as in the best comedies, we see the artifacts of secular life hopelessly and hilariously squandered.

Because of its narrow focus on art-related texts, the collection may reveal more than one might expect about the Swiss writer, who preferred to leave his spirit at the threshold of the page — but there is still plenty of the familiar charm. In a text on Fragonard, we find a typical Walserian aside: “I was frequently flânuering my way through the city’s arcades as well as its pastoral surrounds, though I am certainly aware that one should not waste time. My conduct, perhaps, possessed something Fragonardesque, for every shop, every public square, every window told me stories and was something like music for me […] The more modest my digs, the more elegant all things elegant appeared to me, the more artistic I found all creations in the realm of art — and joy and love struck me as all the more amiable and lovely.” Typical to Walser’s work, an open, earnest approach — to standards of fashion or to the appropriate uses of one’s time — is contradicted by its own thoughtful benevolence. Just as the subjects of Fragonard’s painting delight in wasting the daylight hours, Walser’s own pleasure is embellished by art’s ability to penetrate his experience with beauty — for him, a wonderful and useless impropriety.

In Looking at Pictures, Walser’s taste veers from decadent pastorals to edifying academics, from his brother Karl’s paintings to various intellectual kinsmen. The aforementioned text on Fragonard, as well as two on Watteau, are particularly inspired. For “A Tiny Little Bit of Watteau,” Walser composed a series of monologues for the characters depicted in Italian Comedians (1720); everywhere their emotional sensitivity is pathetic and inevitable in equal measure. From Narcisse Diaz de la Peña’s The Forest Clearing (1875), depicting a mother and child at the edge of the woods, Walser extrapolates an end-of-innocence story, as the mother abandons her child to learn the harsh but simple lessons of nature, “so that it might be pleasing to others.” With a short essay on the life and work of illustrator and writer Aubrey Beardsley, Walser evokes the anxieties of an artist: Beardsley’s hypersensitivity and indulgent tastes have perhaps relegated him to the fringes of current (to Walser’s era) conversations, but having imparted upon his work a unique grace, it may at least live for those few who wish “to appear to oneself quite refined.” And on Van Gogh’s L’Arlesienne, he summarizes his general feelings about art: “In the picture, many questions find their finest, most subtle, most delicate significance — which is that they cannot be answered.”

In general, Walser’s dark and peculiar humor resolves the human condition of hopeless toil to a literal position of servitude (for example in his great novel Jakob von Gunten, 1909). Walser’s fictional artists, however, are impetuous and defiant of such servility. Full of élan, overflowing with the spirit of nature, the narrator of “A Painter” decides to leave the auspices of his patron’s home, despite having fallen in love with her. And what would be so bad for the title character in “Scene from the Life of the Painter Karl Stauffer-Bern” to abide his patron lover’s permission, especially when that means speaking and working freely? As befits their upper-class rearing, this historical-fiction shows Stauffer-Bern and his partner, Lydia, to be entirely overindulged. Nonetheless, these artists are connected by their grand overtures to Nature and their unflagging individuality, keeping them oblivious to the glaring flaws of their behavior. Walser’s relative exaggeration of their bombast or brooding interiority appears filled with awe and disdain.

“A Painter” also presents a brief portrait of a sickly poet, who has come to the patron’s house to die. “What wondrously gleaming eyes he has,” the painter narrator recalls. “How everything in him shimmers and laments. A truly, truly veritable poet: at the same time beautiful and repulsive.” The poet, crippled by his life, has nonetheless remained open to its indulgent devices; he then serves as the subject of the pretentious painter’s melancholic masterpiece. Throughout Looking at Pictures, we see Walser where he sees art. It is a collection of fragments, recollections published in newspapers and journals, some only recovered posthumously. A truly thorough gauge of his opinions and influences from art may be impossible to assume from this collection — certainly some of the texts seem hardly to depend on ever seeing the artwork discussed. But the small volume does see Walser square himself with art: it as an agent of fate, a darkly humored hand acting stubbornly, ineffably, through and upon its subject.