Like many Palestinians, artist Emily Jacir has a conflicted relationship with the notion of “site.” Much of her practice examines site-related loss and hindered site-to-site movement. She fathoms, through installations, interventions, films and objects, what T.J. Demos, in his essay Desire in Diaspora, calls “the impossibility of sitedness.” Yet the site of Jacir’s most recent show — an extensive survey titled “A star is as far as the eye can see and as near as my eye is to me” — is critical: it provides added depth to an already profound constellation of multi-layered works.

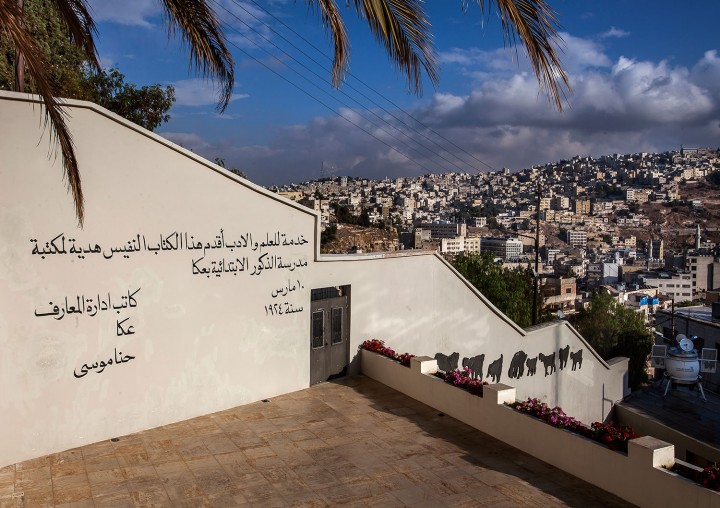

Darat al Funun has been an artistic and cultural locus for artists from the Arab world since its beginnings in 1988. Perched atop one of Amman’s vertiginous hills, it is at once steeped in history yet inspiringly forward-focused. Vestiges of a Roman temple grace its garden, and six historical buildings — each as unique architecturally as their past inhabitants — have housed some of the Middle East’s most stimulating contemporary art exhibitions. The brainchild of artist Suha Shoman, Darat al Funun is both a lifeline for contemporary Arab artists and a proving ground for undiscovered talent.

Artists traveling to or from Palestine pass through Jordan — itself home to a vast Palestinian population — and generally make Darat al Funun an obligatory stop. Jacir was one of these habitual “nomadic” visitors, for whom the site became her “secret bedrock.” She roamed anonymously through its houses in the early 1990s, and shed tears when she finally had a show in the same hallowed spaces in 2006.

Beyond the anecdotal, the Darat endows Jacir’s work with a significance it would not have elsewhere, the most obvious example being the harrowing ex libris (2010–2012). Shot secretly with her cell phone in the bowels of the Jewish National Library in Jerusalem, the work documents the thirty thousand Arabic books wrested from Palestinian homes and institutions by Israel in 1948. Catalogued under the slippery nomenclature “Abandoned Property,” the books teem with life — flyleaf dedications, marginalia, coffee cup stains, wayward scraps of paper, dried flower petals. The clandestinely shot close-ups of the innards of the ownerless tomes are propped on shelves lining the walls of one of the Darat’s galleries, directly below the library, visible through two ceiling-level openings. The hovering presence of books knowingly preserved and intended for public use amplifies the poignancy of Jacir’s mediation on loss. As does the familiarity with these individual stories: many Amman gallery-goers know the families of the dispossessed book-owners; Suha Shoman even recognized her grandfather in an excerpted photo. Interestingly, ex libris makes an unlikely parallel between books and land: both “Abandoned Property” and “Absentee Property” are hinged by illicit seizure and longed-for restitution. Selected flyleaf dedications live as eye-catching murals in the streets surrounding Darat al Funun, further anchoring the link between an unrecoverable loss and a physical, territorial claim.

While Jacir’s impulses seem split between research-heavy undertakings and more immediate, visceral reactions to the Palestinian plight, a sharp, ironic poeticism is woven through much of the work. “A star is as far…” embraces the gamut of Jacir’s artistic approaches: the covert investigation of ex libris and the video Crossing Surda: A record of going to and from work (2002); the excavation in Today, there are four million of us (2002); and the public interventions of Sexy Semite (2000–2002) and XMAS Intervention (1999–2000). Some works, like the rarely seen Everywhere/Nowhere (1999) — an oversized, masking-tape-covered box, similar to those used by movers transferring household possessions, squeezed in a room that can barely contain it — spark multiple questions with an economy of means. Others, like the audio piece Untitled (servees) — a site-specific work at the Damascus Gate in Jerusalem from 2008 featuring Arabic taxi drivers shouting the names of destination cities today inaccessible to most Palestinians — are immersive, lingering.

Many years ago, work by Palestinian artists was largely invisible by international standards. Today’s global recognition of mid-career Palestinian artists (Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme, Taysir Batniji, Ayreen Anastas and Khalil Rabah spring to mind) points to forces afoot that have, on one hand, prepared the ground for the reception of their work on diaspora and occupation, and, on the other, contributed to their artistic and political engagement. Driven by its mission to support artists and stimulate exchange, Darat al Funun is a regional touchstone, its unique legacy fueling an influence that stretches well beyond the confines of its hilly enclave. While shows like “A star is as far…” (not to mention the depth and integrity of its own collection) should catapult the institution into the international limelight, Darat al Funun remains invisible to the global art world. But like the engaged artists it has hosted throughout its twenty-six years, perseverance is its mantra. Tellingly, a 2010 neon sculpture by James Webb, holding pride of place on the façade of the headquarters, recasts the title of a Smiths tune in blazing homage to the Darat’s resolve. “There is a light that never goes out” (in Arabic text) slices across the Jordanian night sky — a beacon both to those who know Darat al Funun intimately, and those who have yet to discover its vitality.