Nathalie Du Pasquier arrived in Milan in the late 1970s. Before that, after leaving her hometown of Bordeaux, she spent a year in francophone Africa, living in Gabon for a while and traveling through Mali and Niger. Her quirky persona quickly adapted to the city’s creative milieu, and in 1981 Du Pasquier appears in the first group portrait of Memphis, the Milanese design brand founded by Ettore Sottsass; when the photograph was taken she was only twenty-four years old, and one of only two women in the group. For Memphis, Du Pasquier designed mainly textiles, carpets and patterned laminates, but also furniture and objects. In Barbara Radice’s 1984 monograph on Memphis, the author describes Du Pasquier as “a kind of natural decorative genius — anarchic, highly sensitive, wild, abstruse, capable of turning out extraordinary drawings at the frantic pace of a computer.” Indeed, her patterns are synonymous with Memphis’s visual syncretism, and probably the whole 1980s aesthetic.

PowerHouse Books recently published Don’t Take These Drawings Seriously. 1981–87, a compilation of Du Pasquier’s unpublished drawings produced during the Memphis years. “These drawings were influenced by Memphis, and Memphis was influenced by them. But the book isn’t about Memphis, it is about Nathalie,” says the volume’s editor and designer, Omar Sosa, also the co-founder of the cult interior design magazine Apartamento. “When you see traces of those drawings in Nathalie’s current work, you are not seeing the influence of Memphis, you are seeing the signature of Nathalie.” Du Pasquier and Sosa carefully selected each of the drawings in the book over the course of two years, in a Dropbox-supported dialogue between the former’s studio in Milan and the latter’s in Barcelona. They decided to organize them into sections according to the size of the items depicted, from the smallest to the biggest — from drawings of jewelry and watches to urban cityscapes, with clothes, vases, carpets, clocks, beds, cabinets and interior environments in between. “It made sense to do it by size,” continues Sosa, “because Nathalie designed a whole world, from a little ring to a whole city. And when it is drawn, a little ring has a lot in common with a big city.”

It’s almost impossible to describe Du Pasquier’s “world,” especially without resorting to the rhetoric of postmodernism: her designs are exotic and futuristic, aggressive and gentle, acidic and sharp. Don’t Take These Drawings Seriously introduces them as the outcome of a tireless daily practice that Du Pasquier pursued on a small desk, in the intimacy of her bedroom, in the flat on Milan’s Corso Garibaldi that she shared with her life companion, fellow Memphis designer George Sowden. “None of the furniture I was designing could have ever fit in that apartment,” writes Du Pasquier in the book. “I could dream of a room completely furnished with my pieces and it was already the beginning of a new way of life. A life with different rituals.” It’s hard to imagine that those “sassy” furnishings were once pastel sketches crammed into half-filled sketchbooks, or that those iconic patterns were felt pen graphics doomed to fade. “I never produced so many things,” Du Pasquier reveals in the interview with Emily King that closes the book. “I have a few pieces of fabric, a couple of objects and so on, but my work was really drawing.”

In a thoughtful introduction to the collection titled “The Surface,” Du Pasquier provides the reader with a theoretical framework for retroactively understanding her naive-yet-cunning drawings. She confides that “the ‘decorated surface’ is low-tech. It is an inexpensive way of bringing elements to a project that come from other spheres, and that has always been an extra reason for my obsession with them.” Dispersed along the drawings is an extensive selection of patterns that Du Pasquier designed in the 1980s as her main source of income. “I suppose these surfaces came from a mixture of what I had seen in Africa and what I was discovering in Milan — the modernity of my own culture, which I had never previously been in contact with consciously.” Applied to textiles, finishes, carpets and so on, Du Pasquier’s patterns would carry “an important decor, a decor that could change [a] room.”

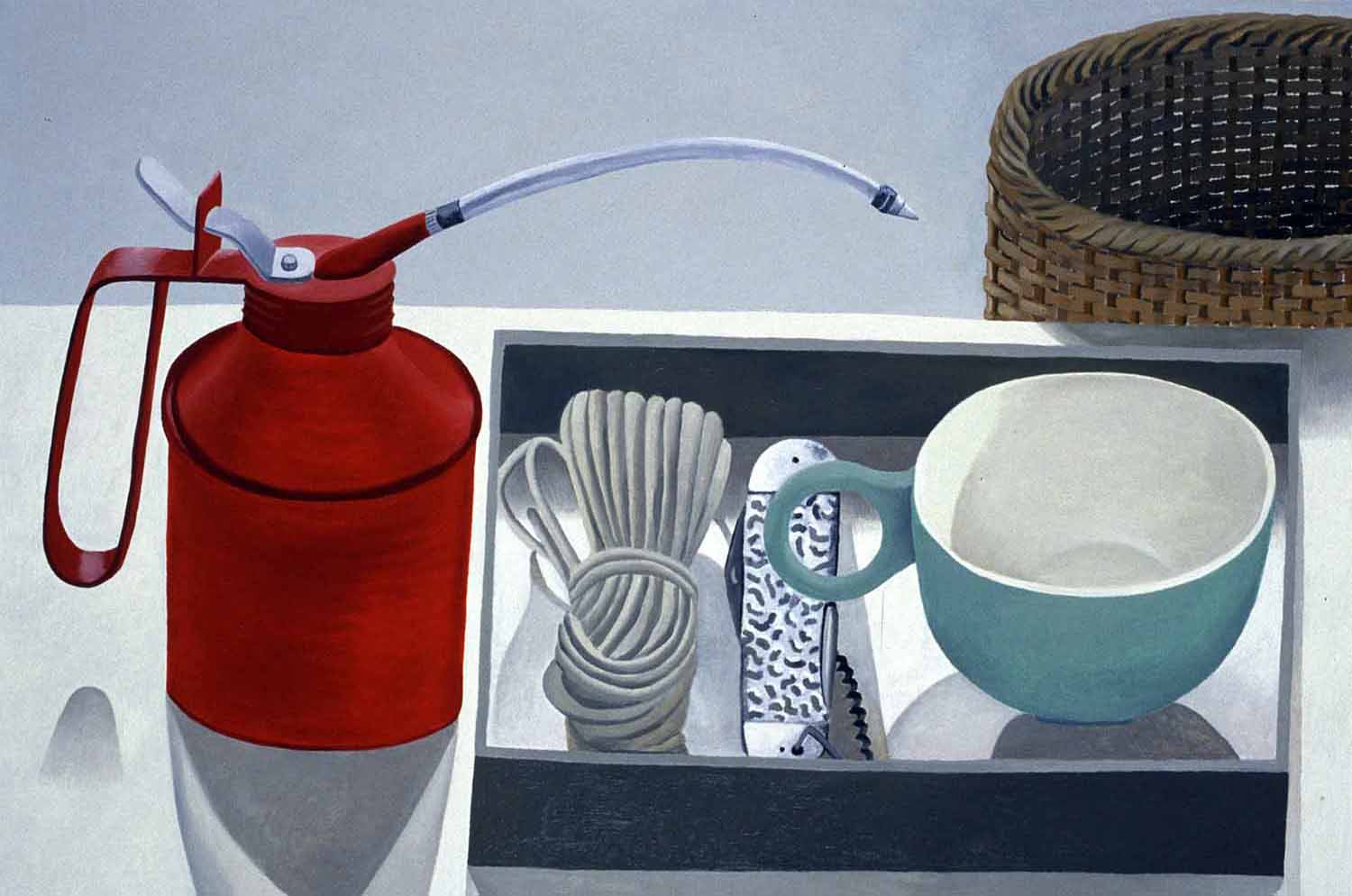

Since 1987, Du Pasquier’s daily occupation has been painting. The everyday objects that fill her studio, organized in carefully assembled constructions, are the subjects of her canvases. This painting practice still informs her fascination for surfaces, the layering of “bodies” in space, transparency and reflection. They reveal a clear, progressive evolution — for Du Pasquier almost a fulfillment of her research — from the 1980s drawings. As such, the paintings constitute another chapter, and could indeed fill other books, no doubt as worthy as the one highlighted here.