Isaac Julien and Yvonne Rainer — friends for over 20 years — have been invited by Flash Art to sit down and talk about their recent respective projects. RoseLee Goldberg moderated this conversation.

Yvonne Rainer: Isaac, I have no idea what you’re doing for your Performa Commission.

Isaac Julien: Well, RoseLee [Goldberg] approached me originally because she thought that my work was a sort of performance on film — something that was between acting and performance. She had written about a performance I did in 1990 called Undressing Icons, which dealt with the controversy surrounding my film Looking for Langston. The film caused an uproar because it depicted Langston Hughes (1902–1967) as a black gay cultural icon, and so the Hughes estate refused permission for me to use his poetry in the film. At that time the only way I could bring attention to the reaction to the film was to do a performance that portrayed the process of making the film and that revealed the film locations. Undressing Icons brought the audience to locations in the main cruising strip in London’s King’s Cross, where the film was shot, and then tried to extrapolate themes from the controversy through reenactments of the film in situ — where the filming had taken place, readings of banned Hughes poems were performed, as you moved through the different locations in the vicinity.

YR: When did you do this?

IJ: I did this in 1990 or 1991. So I had this and other attempts at performance, and as you know, I have this history of working with dancers like Bebe [Miller] and Ralph Lemon in Three, and working on The Long Road to Mazatlán with Javier de Frutos. I’ve always been interested in movement because I danced when I was younger. And I have this image, Yvonne, from a film that you made, which I still remember to this very day — one scene, where there’s a movement of the arm, and it’s sort of like a flashback. The movement is not balletic but it has a flow, and the moment registers as a trauma of some kind.

YR: Are you thinking of Lives of Performers?

IJ: Maybe it’s Lives of Performers…

YR: This movement? [She flashes her hands across her face.]

IJ: Precisely!

YR: I was still making choreography then. There was choreography in my first two films. So you’re collaborating with the choreographer Russell Maliphant on your piece for Performa?

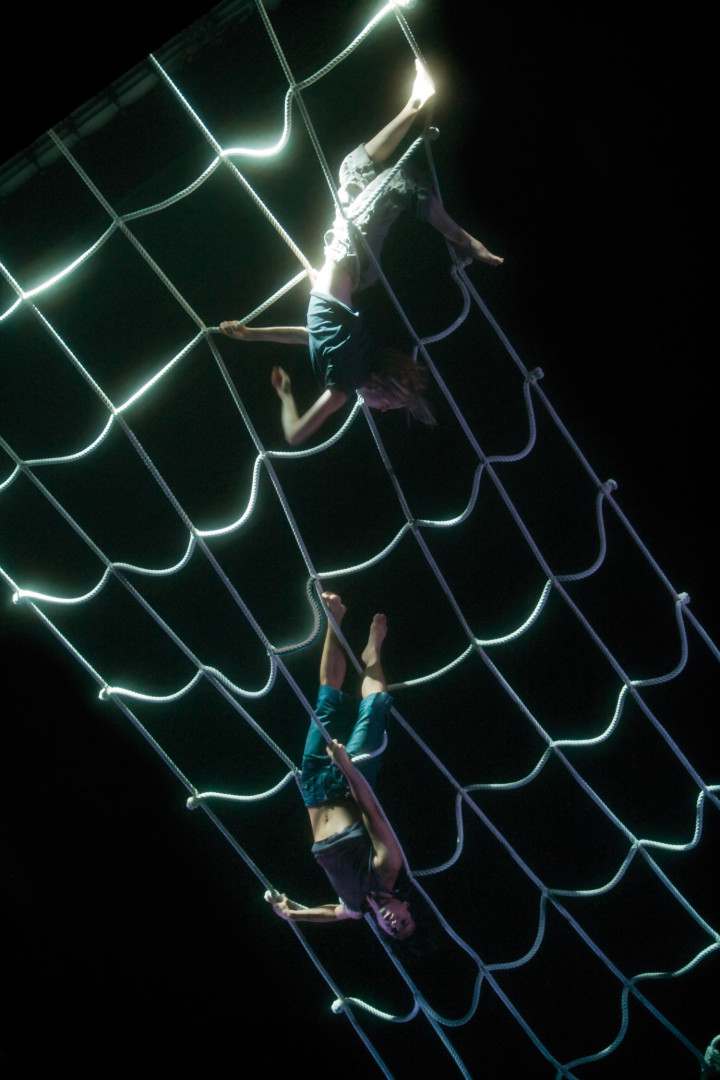

IJ: Well, Cast No Shadow is a project in three parts. The first part, True North (2004), is a film that was already made. We’re basically deconstructing True North, creating gaps in it, and re-editing for the stage. The film isn’t so much dance as it is dealing with the shape of the body in relationship to landscape and how this can move across three screens; then there are these places where light gets choreographed into the gaps and the body moves through them.

The second act is Fantôme Afrique (2005), a film which already has choreography in it by Stephen Galloway, who worked with William Forsythe. He performs some choreographed ideas related to the architecture of the buildings in Burkina Faso that we filmed inside. The last part, Small Boats, is a work that we’re developing now.

It’s being shot in Sicily, and traces the idea of expeditions that runs throughout the project.

YR: So for Small Boats Russell’s doing the choreography and you’re doing the film separately, and then you’ll bring them together?

IJ: Well, the film and the choreography are being generated together, in dialogue. In a way, I started my Performa Commission with a working Performa program title RoseLee had come up with, Dance After Choreography. I thought that was a really fantastic title. I was thinking about the Judson Church group, about your Trio A and all those sort of works, when RoseLee mentioned this Dance After Choreography idea as a way of trying to think about choreography as connected to ideas, not just to dance or the more orthodox trajectories that you tend to see in relation to movement. I saw Akram Khan perform at Sadler’s Wells recently, and when you look at his work it reminds me of some aspects of the early Judson group. He recently did a piece with Sylvie Guillem in which he’s talking to the audience. Then he goes into a deconstruction of what he’s trying to do, and then she deconstructs what she’s trying to do, and then the dance becomes a meditation on that whole process as well. This return to the kind of deconstructionism used by Judson is very interesting.

YR: RoseLee originally approached me to reconstruct This is the story of a woman who…, a mixed-media piece from 1973 that included some Judson material in it, like my first solo, and Trio A. But there are things in that theater piece that I couldn’t possibly reconstruct — and there are few photos, no video documentation, nothing. So I said that I couldn’t do that. But then I went to London, and saw this recording of the BBC’s Riot at The Rite, a dramatization of the making of The Rite of Spring in 1913, and I was turned on by the reconstruction of the scandalous evening, and how the film cuts between the dance and the unruly audience. So then you and I met — we ran into each other or something.

IJ: That’s right — we bumped into each other in Chelsea…

YR: We went to the Empire Diner, and I was describing The Riot at The Rite to you, and you got on the phone to RoseLee. I just had this idea and hadn’t even begun to think where and how. You fired up RoseLee who then said, “Do it!” And that’s how I came to be a part of Performa07. The piece that I’m making, RoS Indexical, has four women in it. We’ve been approximating the fragments of movement that 42 dancers do in Riot at The Rite — a reconstruction that is pretty much what Millicent Hodson did for the Joffrey Ballet in 1987, which I think was taught to the Finnish National Ballet, which performs in Riot at The Rite. It’s diabolical — in the Stravinsky score the counts are so irregular. There’s a steady pulse, but then sometimes it’s 5 to a measure, sometimes it’s 6, or 7, and the dancers have to count like mad, all in unison counting away. And Performa got me the BBC soundtrack too — so instead of using the original, orchestral The Rite of Spring I’m using the BBC soundtrack from the film, which is muddied by all of the noise coming from the audience.

IJ: Wow! That’s fantastic!

YR: But then the second half of the performance is going to be totally off the music. It will be based on documentation of Robin Williams and Sarah Bernhardt performing. We’re using these silent films from 1911 of Sarah Bernhardt. And then Robin Williams, the comic — he’s like an explosion on the Duchamp staircase. He’s utterly incredible in the way that he moves. RoS Indexical is choreographic in that it’s all about movement, but my primary interest is these historical, avant-garde moments — like 1913, when what Vaslav Nijinsky was doing was so radical. I’ve always been interested in those avant-gardes from 1900 to the present. I consider my work to be in a direct line from Duchamp, Cage and Cunningham, but also from those earlier avant-gardes.

IJ: When I try to think about radicality, I think that [choreographer William] Forsythe, generationally, is the only person I can think of who’s continuing that kind of work, in that…

YR: Scale?

IJ: Yes, scale. And working with the idea of radical disjuncture. In a way, Forsythe is the only person returning to this linguistic question — playing with the linguistics within the field of vision during performance. I think that the linguistic aspect is very important.

YR: I think so too. I’m using signs with words on them that drop at various points during the performance; what these words are and how explicit they will be has become a big issue. I want to avoid referring directly to the collaboration between Nijinsky and Nicholas Roerich, the set designer and anthropologist who was responsible for the costumes and the basic ideas of The Rite of Spring — tribal rituals, sacrifice of the virgin, all of that. So rather than using categories like “culture,” “archaeology,” and “tribe,” I’m thinking about much more ambiguous words like “savage,” or “who, me?” or “sofa.” The only object in the space will be an overstuffed chintz-covered sofa that the dancers occasionally sit on to rest up from their labors.

IJ: That sounds fantastic!

YR: I keep writing down words and crossing them out. It will be something like “loss,” “save,” “savage,” “suffer,” “lunch”… a combination of the emotionally loaded and the banal. I’m tossing these words in the air to figure out what I want to direct the audience’s attention to linguistically and historically. It’s still an ongoing process that I haven’t settled. How did language work into your project?

IJ: In True North there’s a text by Matthew Henson from an interview that was conducted in the ’50s by a student at Columbia University. The student was able to get Matthew Henson to confess about the argument that he had with [explorer Robert] Peary when they went to the North Pole. So language is in the soundtrack, but rearticulated through the voice of a woman, Vanessa Myrie, who plays the Matthew Henson figure in the film — so all of the research is reconfigured. It’s really a translation of that narration from the interview into the contemporary. I think interest in the linguistic aspect of performance is something that has disappeared almost completely from the practice of this generation of artists. It’s really interesting to think about language as something which can make an intervention.

YR: Recently there was this Q & A after a lecture that I gave, and I was talking about AG Indexical (2006), and someone asked me if I thought that radical politics was involved in it, and I was kind of stumped, but then someone reminded me that to have four women do the work that originally was done by four men [in Balanchine’s Agon, which AG Indexical re-envisions] is a critical statement about gender. So if you want to look for moments of specific radicality or critique, there are instances within what I’m doing, but in RoS Indexical I think that the overall concept and project is more of a mixed bag — a mix of nostalgia, homage and analysis. It’s a challenge to ideals of retrieval and reconstruction, and to the idea of a canon.

IJ: Absolutely. I was thinking about the rearticulation of the archive in Fantôme Afrique, which has references to people like the Surrealists, and Michel Leiris, going to Africa — this connection to Francophone Africa, and its relationship to a kind of modernist moment in ethnography. It was a kind of a bricolage approach to using the archives, and reconstruction, and documentary, and I was thinking about all of those things in terms of the editing and the montage. There’s a sort of politics in the aesthetic process, which isn’t foregrounded.

YR: Implicitly, my project is about memory in relation to history, how history gets codified, and how memory then gets reconstructed, reinvented. I mean, I’m riffing off of a dance for 42 people with four people. It’s very strenuous — it’s impossible, in a way — and because the dancers have such different histories, and abilities, and training, and ages — from 30 to 60 — you see what you might say is a clash of abilities. I guess I’m interested in the impossibility of reconstructing something, first of all, because no one remembers it, and it’s been transposed through various layers of memory, and recording, and screening, and so on. Then there are the discrepancies between the ideal of the original and the impossibility of an authentic copy and the very visible impossibility in terms of the varying abilities of my dancers. So it becomes something else entirely, and I don’t even attempt to say it comes anywhere near to an original, because it wipes out the whole notion of such a possibility. I haven’t answered to my own satisfaction the question of why I attempt this impossible project.

IJ: It’s fun when you can work with a text in a way, isn’t it? You can deconstruct it, and play with it, and extrapolate it the way you want to, and rearticulate it…

YR: Right. Someone else did all the work. [laughter] Like I told someone, “I’m stealing!” And she said, “From your dancers?” I said, “No! From Nijinsky, from Balanchine…”

IJ: I think it was James Baldwin who said, “The crown’s already been bought and paid for — all you have to do is learn how to wear it.”

YR: I think I’m wearing it a little askew. And sometimes I’m stomping on it.