The fragment involves an ambiguous altercation between singularity and dispersal, atomized integrity, and fracturing action. A fragment, like fragmentals, is never solely isolate. This interdependency, that is, on the matrix of other fragments, correlates to Yu Ji’s sculptures and their cloudy adumbrations of metamorphosis, pulverulence, granularity, and ever-ashen efflorescence. Yu Ji’s industrial materials of concrete, mortar, and iron induce creation and its demolishment, infrastructural adhesions lowly weathered and abraded, distilling the physical, polluted nexus of urban industry and natural landscape.

The fragment speaks to the fallacy of hermetic autonomy, which Yu Ji renders in bodies that evade the burden of wholeness. Four variously truncated concrete torsos collect on the floor near the entrance to “Against Shadows”: her series “Flesh in Stone” (2012–ongoing) and “Jadeite Joint” (2021). Concrete is eventually fallible; as an anonymous material it risks in turn imbuing this “flesh” with a questionable anonymizing or depersonalizing quality, in keen recognition of the human cost of construction. Yet cavities of each contracted body are filled with soap, most notably in Jadeite at the knee joint; its axis enables the slip of state into soluble substance, certain lather. With felled limbs and obliterated joints, on occasion these sculptures expose their internal structure of iron armature. Cold and stoic, the congregated bodies of salve and severance are little figurative ruins: not mere remains, perhaps, but a means of remaining.

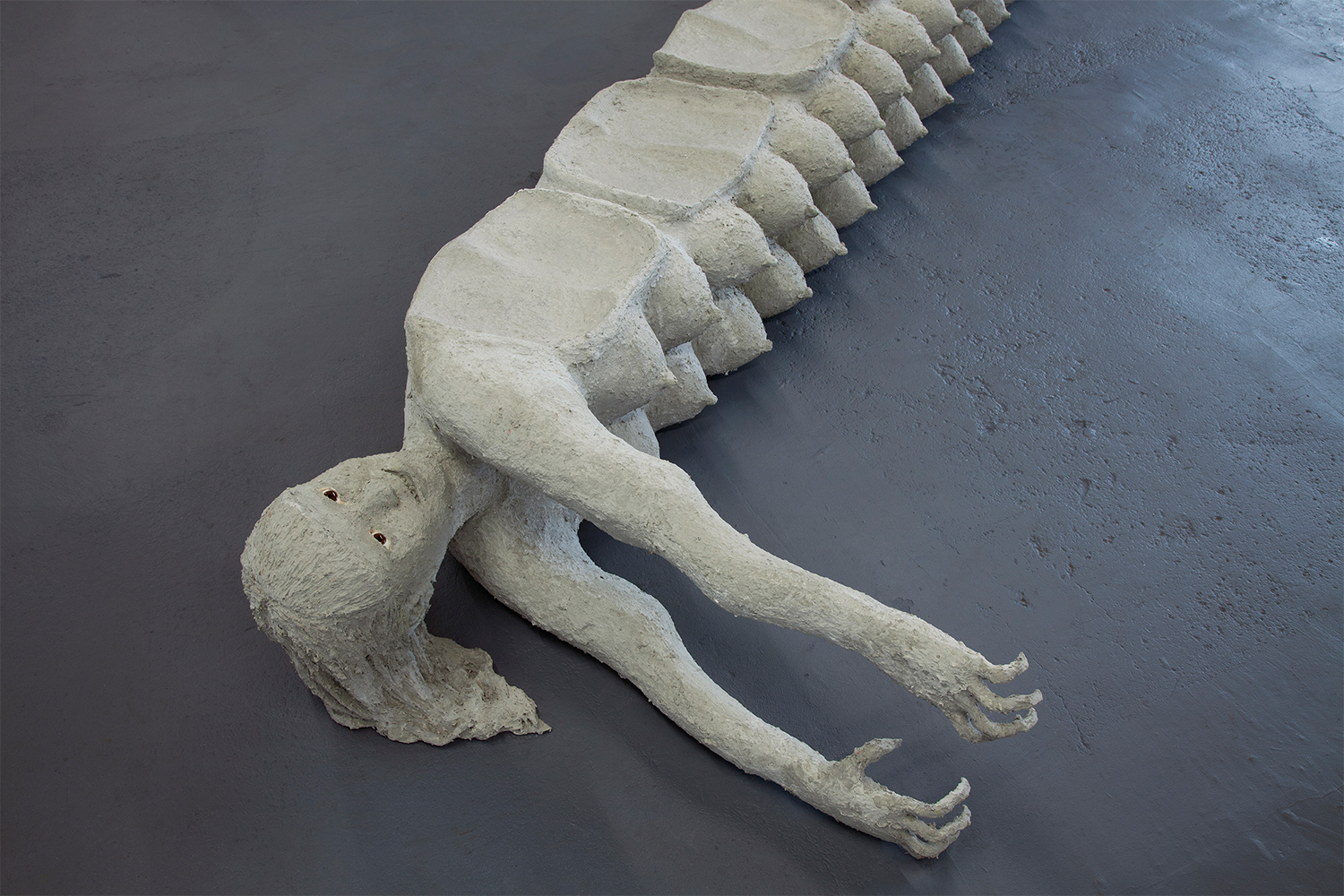

Of lapsed temporalities are Flesh in Stone-Ghost No. 1 and 2 (2018), which originate from live sittings in which male models are instructed to test the limits of their bodies. Yu Ji committed such contortions to observance, bathing them in memory while studying photographs of ancient archaeological sculptures from China, Cambodia, and India, later creating clay models to fabricate resin molds for her studies. In this way, they are between an observed, intuited, and remembered figuration. The resulting cast limbs of concrete and plaster are strapped in iron brackets either bowed and kneeling as conjoined concertina or sutured to the wall as an unfurled wing. Concatenated or fanned, their mute volumes are reliant and symbiotic despite, or due to, their limiting brace. Yu Ji’s ghosts suppose one can still speak of presence within dissolution. These remnants are structures of carnal tension, heavy vestiges of mutated and remembered energy. Yu Ji’s exploratory regard for these once-diffident, apparently impoverished materials benefits from this latent, strained physicality, becoming both tangible and spectral.

More succinct are three large poles of Chinese fir carved in a helical twist echoing the wrung eggshell-blue neoprene cords that harness them, stretched and arrested, just: a material dependency at continual risk of undoing. Other freestanding sculptures form an archipelago; two cast knees submerged in charred wax are knolly meteors or protrusions of igneous rock. Hypogean and perishable are rocky chunks of soap that appear, in all their geotic cracks, like lumps of olivine or nephrite. In one specifically, its auroral green appears oily, mineral, velutinous. As modest, metamorphic hunks they surpass their adjacent rubble of compressed, evidentiary action.

The pang of perviousness sounds in the accompanying video documenting previous performances at Sa Sa Art Projects, Phnom Penh, and at the Centre Pompidou x West Bund, Shanghai. In the latter, experimentations occur within a makeshift studio sealed off by plastic sheeting. Inside, Yu Ji’s practice emerges as a dusted sensorium populated by wood, jackfruit, and concrete, probed by variations of material detrition, meditative deconstruction, and explosive exertion. Empathy, perception, care, and pain are its oscillating registers. As a montage of previous projects, however, the video feels like a crutch to evidence the action embedded within the surrounding sculptures, an annotative aside.

Tenaciously bound, mutually reliant, or merely solitary, one experiences the sculptures of Yu Ji’s landscape as strangely marooning, between dismembered relic and latent effect, a field of remainders. Perhaps the impression surfaces, understandably, in lieu of an enacted sense of transmutation or site-specificity, such as informed the recent exhibition “Wasted Mud” at Chisenhale Gallery. Crumbled, bracketed, and temptingly dissolvable, this scene is sparingly washed elegiac, with stasis stirring its élan vital suspended: potently remote.