A gold curtain shimmers from a flagpole and catches the light; crystals cascade in thin streams and reflect rainbows; sunrays shine through stained glass, blue bleeding onto the floor. Wu Tsang’s Gropius Bau exhibition, divided into seven rooms, comprises film, photography, sculpture, and sound, and is both materially seductive and precisely refined. Known for her films that use performance to explore queer culture, identity, and the politics of visibility, Tsang upends the latent violence of the camera to suggest empowered modes of resistance.

At the entrance to the show three panels of stained glass hang from the ceiling — Sustained Glass (2019), a collaboration with Fred Moten, boychild, Lorenzo Moten & Hypatia Vourloumis. A poem is legible, marked by repetition and overlay, as well as breaks and obfuscation. Phrases include: “He made himself nothing,” “They kill him every day,” and “Giving is everything.” An accompanying sound piece, Sudden Rise (2019), speaks aloud sections of this text, again using layering as a strategy that enables multiplicity and numerous perspectives. As with the state of glass — fragile transparency that is actually neither liquid nor solid — identify here is defined ever moving.

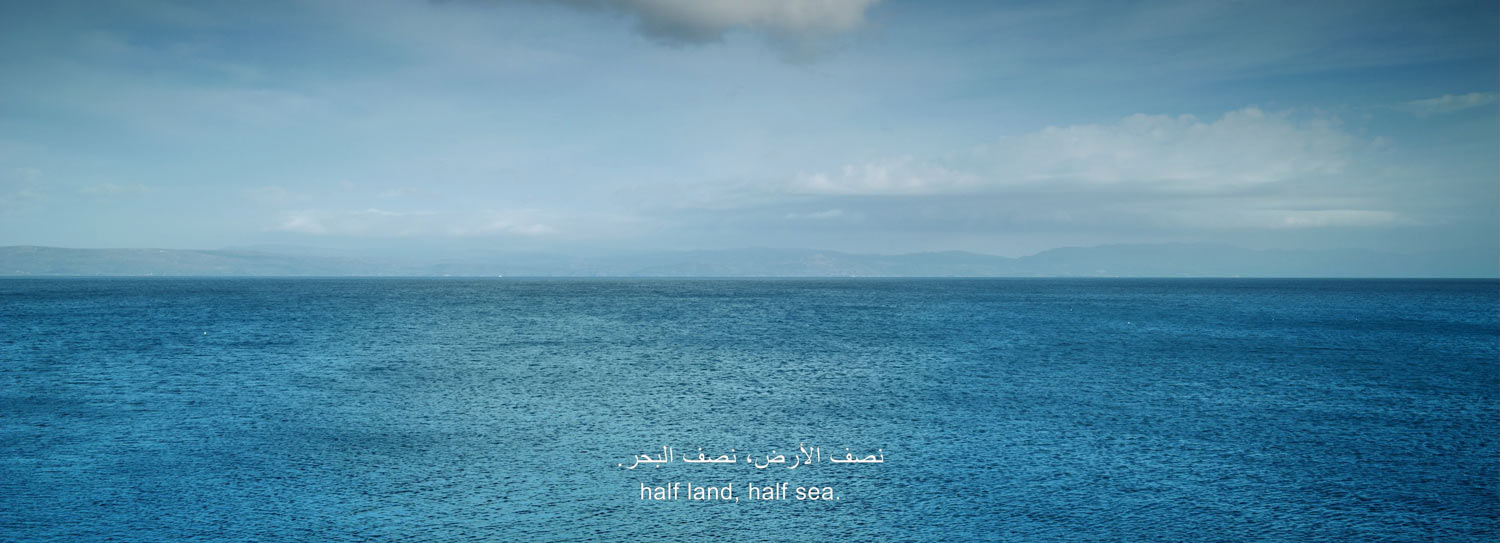

The exhibition’s title, There is no nonviolent way to look at somebody, derives from a poem written with Fred Moten, and suggests that judgment is inherent to perception; that to look and assess is to limit someone, interrupting the fluidity of being. It fixes us. It too points to the saturation of violent images that circulate around us, and indeed, penetrate our consciousness. Such images have documented the refugee crisis, and Tsang’s new film, One emerging from a point of view (2019), was shot on the Greek island of Lesbos, examining the experience of migration of 850,000 refugees.

It features a sheep farmer who cites that “the hardest thing is to continue to live.” Life jackets are seen piled and whipped with rain; sheep cross a river, framed by birds landing on the sea; the myth of Yassmine is told, a woman exiled from her home by a king and eventually murdered by him. The film’s magic realism blurs fact and fiction, yet honors real lives stained with loss of life, land, and identity: a crisis of representation for people who are killed every day because of how they are looked upon.