Hidden stories and marginal narratives have attracted Wu Tsang throughout her artistic career. The belief that history is nothing but a mental construct, the product of what we make of it in the present, has guided Tsang in experimenting with narrative strategies — films, installations, performances — that challenge the existence of a univocal and predetermined understanding of reality and art. The tools of images — not only language but also movement and sound — become a means to uncover stories and analyze all possible perspectives.

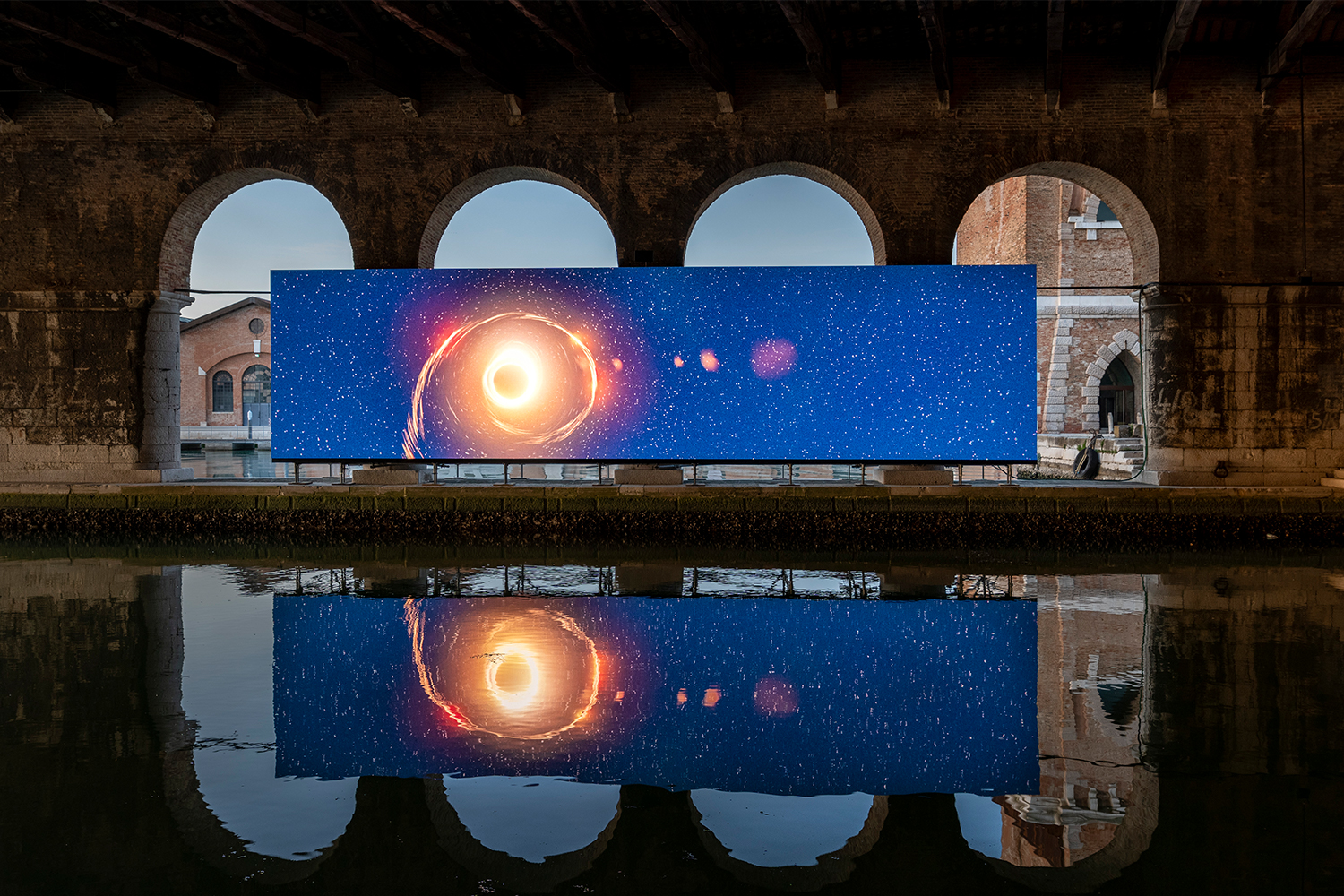

The very idea of perspective is disrupted in Wu Tsang’s multidisciplinary adaptation of Moby-Dick, Herman Melville’s novel published in 1851. The project takes the form of four discrete parts: a feature film, MOBY DICK; Or, The Whale, recently presented in Venice; EXTRACTS, a film installation produced with the collective Moved By the Motion for the Whitney Biennial, which shows the process of making the movie; the sound installation Of Whales, part of the 59th Venice Biennale; and a forthcoming VR adaptation to be presented at Art Basel.

In the following conversation with Noam Segal, the artist discusses how these different approaches to the same material reveal a multitude of possibilities and perspectives, some of them quite unexpected.

Noam Segal: Wu, thank you so much for joining me today. I’d like to start by asking you about the research that led you to your new film, MOBY DICK; Or, The Whale (2022), and how you incorporated these sources into the structure of the film.

Wu Tsang: I really came to Moby-Dick through the readings of people who have been inspired by but also critiqued the novel. I think the idea of the Great American Novel is something I might not typically want to take on, because I’m not generally interested in the canon, but it was such a provocative, rich subject matter that I saw entry points. One was through a friend of ours, a film studies scholar named Laura Harris, who was giving a talk about C. L. R. James’s book Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In, which is a postcolonial reading of Moby-Dick. Laura’s reading of Melville via James was an important opening that got me super excited to think about how something so old and historical can also have a very contemporary feeling to it. The book is also a prism through which to look at the present, even if it’s a very old story.

I also was looking at different research around the maritime history of that time period. There’s a book called The Many-Headed Hydra (Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker, 2000) that, like C. L. R. James, focuses on the “motley crew” of sailors, and how this social class of people were coming from all over the world. The book talks about how the ship was a place of mixing for cultural exchange, news and information, and even spreading revolution.

So we were looking at accounts and depictions 166 167 of the social life of sailors, and there were many other layers of research around the set design and the costume design, which brought these themes of homosociality and labor into the present. The costumes were designed by Telfar and Kyle Luu, who is our collaborator that we always work with. Telfar had done a collection at Pitti Uomo the year before, in Florence, which I had seen and really loved, that reminded me of nautical and colonial dress. We were sharing a lot of images, and he made some original designs too, like for the harpooneers’ coats. I love that he paid so much attention to the details, distressing the fabric and adding dirt and armpit stains. In the end it’s not so obvious that the clothes are Telfar—it looks authentic but there is something contemporary and playful about it.

NS: How does abstraction play out in this film? For example, Fred Moten’s voiceover includes a paragraph about abstraction, and I wonder how you were thinking about the role of abstraction in a distinctly narrative work.

WT: So that quote in the voiceover actually comes directly from C. L. R. James. And I think the point he’s trying to make, which is an important one that we were trying to explore in our adaptation, is this concept of “the Plan.” Moby-Dick begins with Captain Ahab announcing his mission, which is not really to hunt whales, but in fact to extract revenge on one specific whale, which becomes his obsession even at the cost of the lives of his crew. He offers a reward of a gold coin, but more importantly he manipulates and NS intimidates the men into following his Plan. I think Jame’s point was that dictators are driven by an abstract idea of progress.

The quotation goes on, “And Ahab? He has to manage things and manage men. Their primary aim is not world revolution. They wish to build factories and power stations larger than all others which have been built. They aim to connect rivers, to remove mountains, to plan from the air, and to achieve these they will waste human and material resources on an unprecedented scale. Their primary aim is not war. It is not dictatorship. It is the Plan…” I think that’s a powerful notion: that most modern forms of political leadership are not even straightforwardly about world domination or war, although we also experience that as well. It’s the drive to organize society in a capitalistic way, for an abstraction.

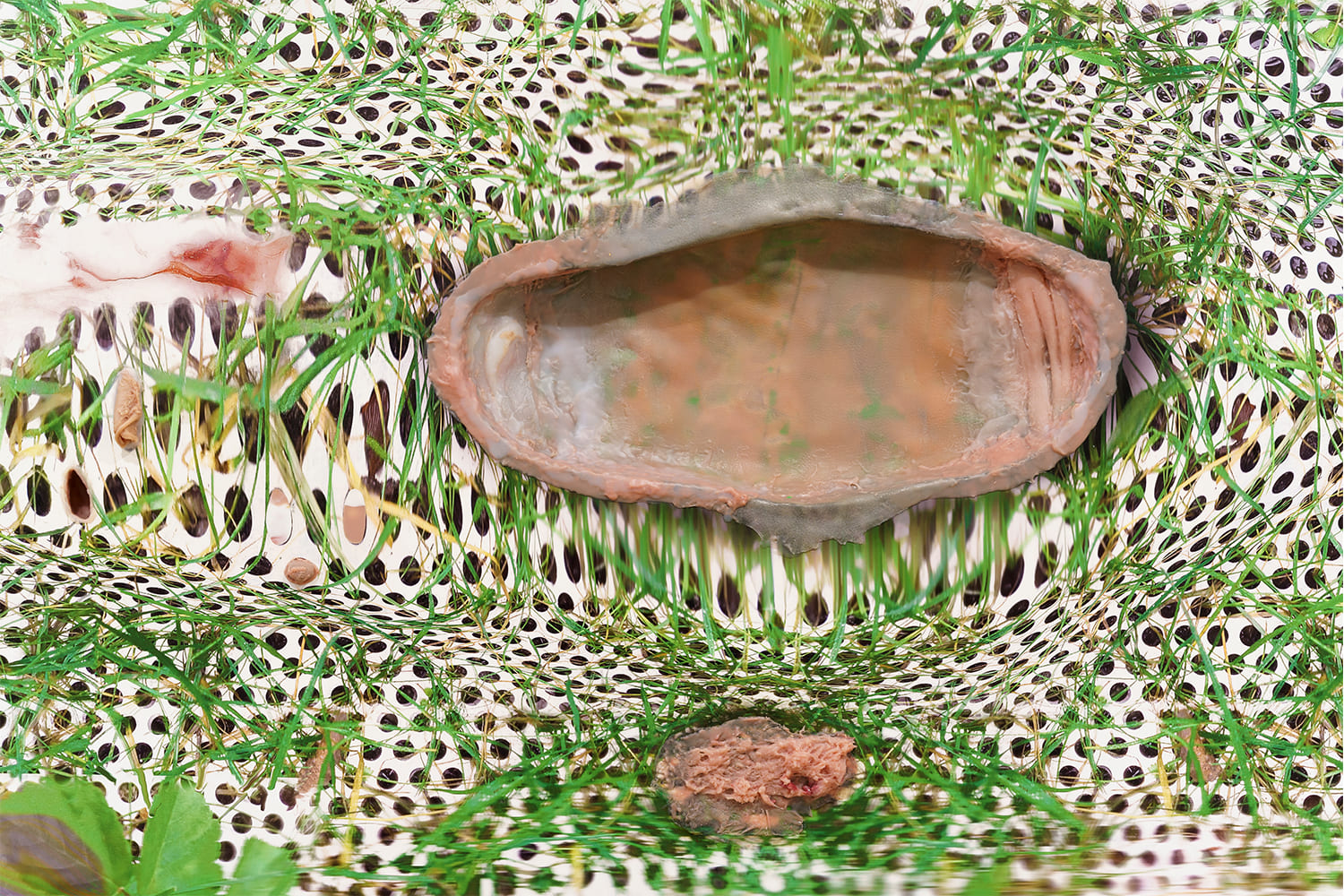

Your question about abstraction also makes me think about it in the aesthetics of the film. And in that sense abstraction is also there, because a lot of aspects of Moby Dick are “too big.” Abstraction became a way to deal with the bigness of everything: our strategy was to try to be really simple. For example, the vastness of the ocean is something that we couldn’t possibly convey. And so, in a way, everything is just done very minimally on a sound stage with a square ship deck that we could turn and spin at different angles, and a projection of a digital ocean that we could manipulate quite a bit. I think that reducing it in that way, and also revealing my mechanism of how the film is being made, was a way of trying to use the tools of abstraction to tell the story.

NS: It is also evocative of an actual experience on a sailboat in the middle of the ocean: your horizon is so close, because you can just see the line of the horizon and it feels like it is closing in on you. Can you talk about the idea of temporality in this work? As you mentioned, the set design and the costumes represent several time periods simultaneously. This is part of how you create an open-endedness that makes Moby-Dick at once contemporary and old. Some aspects of it can even seem futuristic.

WT: Well, it’s a big question. I was really inspired by looking at early silent films, before the invention of synced sound. I think that filmmakers of that era were very innovative with their visual storytelling because they could not rely on a coherent sense of reality. Synced sound conveys that the camera is capturing “reality,” where the camera becomes a bit invisible to the scene because the visual and sound are synchronized. But before that moment in cinema, there were not the same rules about how to construct reality or tell a story.

I became particularly interested in the old style of visual effects using rear projection, which was started in the 1930s. The technique involves putting the actors and the set pieces in front of a screen, and lighting the scene against a projected background, so that the world looks continuous. In the case of Moby Dick, our projected VR ocean was obviously not real, but there is a surreality and cohesion that comes from committing to a distinct style of storytelling, even if it is obviously not real.

NS: The apparatus of the silent film really advanced those ideas of open-endedness and a temporality that is spatially encoded in the film. Can you share what motivated those choices? There are so many alleged disadvantages or limitations in the silent film, but you used them to great advantage in the creation of a historical film that is not limited by a specific gaze or colonial worldview. This seems similar to the way you work with visibility, accessibility, signification, language, and perspective in your previous works. Can you comment on this approach in this film and your work at large?

WT: Moby-Dick feels like the present as much as the past, and I wanted to create a world that transmuted through time periods. That impulse seems consistent with the ways that I have worked over the last ten or fifteen years. I’m often digging below the surface of history, so to speak, to try to uncover queer and trans experience. If I want to tell this kind of story, I have to be inventive because the aesthetics and the narrative style does not necessarily exist. But anyway, history is a construction itself—meaning that it’s always constructed by us in the present. That has always informed how I make things.

I work in a collective called Moved By the Motion. We are here in residence at the Schauspielhaus Theater in Zurich for the last three years, and we’ve been working together since 2014. One thing that we continuously love to explore is how to communicate outside of language, because everybody in the group is coming from a different background. Josh [Johnson] is a choreographer coming from dance, and Asma [Maroof] is a musician coming from electronic music, and Tosh [Basco] is coming from performance art. So making Moby Dick together, we have a very intuitive process around how we can tell the story through images and movement and sounds, whether or not we share a common language. Also around the time that I was starting to think about Moby-Dick I happened to see the original Phantom of the Opera (1925) with a live orchestra, and I was so struck by how live it felt, even though there was a screen and a projection of a prerecorded image—it felt very alive with the orchestra interacting with it.

I was thinking this would be a very interesting thing to try in the context of the theater, in the context of Moved by the Motion because we are working between live performance and film—it was exciting to try a hybrid. Most of the performers in Moby are actors that work at this theater. Theater actors have to be “big” on stage so that the audience can understand from a distance. It’s interesting to do that for the camera, because usually that acting would be considered too big, but if you look at early silent film, that was a moment when theater and film were merging from the other direction. And so, it’s interesting to take it from cinema back into theater.

NS: Let’s shift to love. The main axis you establish for human relationships on the boat is the romantic love between Ismael and Queequeg — a relationship that remains ambiguous in Moby-Dick. How does this queer love map onto the racialized, hierarchical relations of the whaling vessel? How does this line up with or disrupt the obsessive “plan” of Captain Ahab in the original narrative?

WT: Actually I think the love relationship of Ishmael and Queequeg is not so ambiguous in Moby-Dick. This is what I love about adaptation —sometimes you don’t even need to stretch something. You can just simply present it as it is, and a little recontextualization goes a long way. So, for example, the opening scenes of Queequeg and Ishmael in bed together, all of that is staged really pretty close to the original. Melville—who knows, I’m not interested in putting labels on people in the past—but I think he had an infatuation with Nathaniel Hawthorne. They wrote each other all these amazing love letters. In many ways, Melville’s biography mirrors Ishmael in the sense that he comes from an educated, well-off family; he even worked on whaling ships himself. At one point he deserted a whaling-ship, and lived in the South Pacific for a couple years and then wrote a couple exoticizing novels about his experiences there. He’s a very problematic figure, but I think in a way that to me feels quite familiar — it feels quite evocative of the politics of our present, which is that to show queer desire does not make it immune from a colonial gaze. Ishmael, but by extension Melville, has a profound love for the characters on the Pequod. But he also calls Queequeg a “cannibal.” The book is rife with very hyperbolic racist tropes, particularly for the people of color, but they’re also quite loving in the problematic way that makes Melville so American. It’s juicy to pull apart and recontexualize.

For me, these kinds of problematics become a way to pull people in, through those tricks of desire and implying without showing. You can pull people in, but then you try to also turn it around and re-frame what is really going on. For example in the scene that follows, Ishmael and Queequeg becoming “Bosom Friends”, we see Ishmael journaling on the deck, observing all the men with an overtly fetishistic gaze — we can use humor and re-present something that’s actually quite problematic without providing the answer for people, but rather invite them to think about it.

NS: Can you talk about your work with the collective Moved By The Motion, that includes Tosh Basco and other participants? Everyone in the film brings something of themselves, by the practice of workshopping this film, the ways you work together to incorporate these voices and this collaboration into the film itself.

WT: I feel really happy and excited that we were able to make EXTRACTS, a companion installation film for the Whitney Biennial, which is collaboratively authored by the collective. It is basically a compendium of different archival materials and performances that happened during the making of Moby Dick. I think it is a beautiful representation of the collaborative performance practice of the group, which is usually happening in the background—it’s actually how we always work. Every time that we’ve ever made anything, there’s always this exploration through performance, and everyone bringing their own perspective to it. We might share a script or a set of references or a text, and there’s a lot of space in that for people to bring, or not bring, whatever they want. And that’s something that’s taken years for us to cultivate with each other. It’s not necessarily easy to do, but a film like Moby Dick would not exist without that history of collaboration and trust that we have with each other.

NS: Can you talk a little bit about your specific relationship to language and the text? Sophia Al Maria wrote the text, and you mentioned that you had to reduce it somewhat. Can you share some of the insights you gained from this process?

WT: Sophia was such a key collaborator. She wrote this beautiful script that ultimately became subsumed in the film. Even the writing and all the dialogue, most of that became subsumed by the image. There’s very little spoken language in the film, and we really had to reduce it to the most limited palette of words. And that was a really interesting process to do with a book like Moby-Dick, because Moby-Dick is so famously verbose. It’s really so much about the language, and Melville really constructs a whole world out of his use of language. I don’t usually work with scripts when I make films because, in the past, I have found them to be a little constraining. But in this case, I knew we needed a script because Moby-Dick is such a monstrously huge book, but also because we were doing this approach with the VR rear projection, which is also known as Virtual Production. It was just super complicated with the set essentially. So we really needed a map, and Sophia was a dream collaborator in this.

In addition to being an amazing artist herself, she has as a background in writing and adapting historical novels for film and television. So she really brought a lot of that expertise and also had done a lot of research about maritime history in that time period, and also had a shared sensibility with us because she’s also an artist herself. So it really felt like we had a very wide palette where we could experiment with telling the story and hold people’s attention, but also really dig deep into the history and the research. I feel she really enabled us to do that with a very graceful touch.

There is so much language that the film is swimming in, but it all got subsumed in the end, in the process of making it. For example, even the Sub-Sub Librarian, the character of Sub-Sub that is played by Fred Moten, we had written and pulled a bunch of extracts for him that we wanted him to read. The Sub-Sub exists in this film as a — in our version, he lives inside the belly of the whale, and he’s a kind of a Jonah-like god figure. He can provide these different layers of research and commentary that maybe the characters in the story are not able to reflect upon themselves. They don’t necessarily have access to time the way the Sub-Sub does. And so even in the writing of the extracts for Sub-Sub, when we gave it to Fred, he also rewrote it himself. And I just said to him, “This is your character and here’s what we want you to say.” And then he rewrote it to find a way for it to sit in his mouth so that it also became his. And that again references back to the collaborative process I was talking about. I also think another metaphor for the way we work is exquisite corpse, because with each person there’s an invitation to alter and obliterate and make it your own.

NS: So the project unfolds in four ways: the film, the live event with the concert, EXTRACTS at the Whitney Biennial, and the whale — the generated gaming algorithm that shows the perspective of the whale within the Venice Biennale. Then there is going to be another VR project launched at Art Basel. Each one of them brings a different perspective to the same event. This happens through medium, but also narration and perspective. So how did you think about it in terms of the medium? What aspects are appropriate for a virtual reality project? Why is something right for a live event, and something else right for the Whitney?

WT: I think with every project, there’s always two central questions. One is audience: “Who is this for?” And then also the medium, in other words: “What am I trying to say and what is the tool to say that?” And I think in many ways, the Whitney, the EXTRACTS installation, and Moby Dick are companions to each other. Because for me, the installation says what the film cannot, and talks about performance and collaboration in a way that a narrative feature cannot. And the feature tells a story in a way that an installation cannot. So each one satisfies different urges — the material has urges to find these forms.

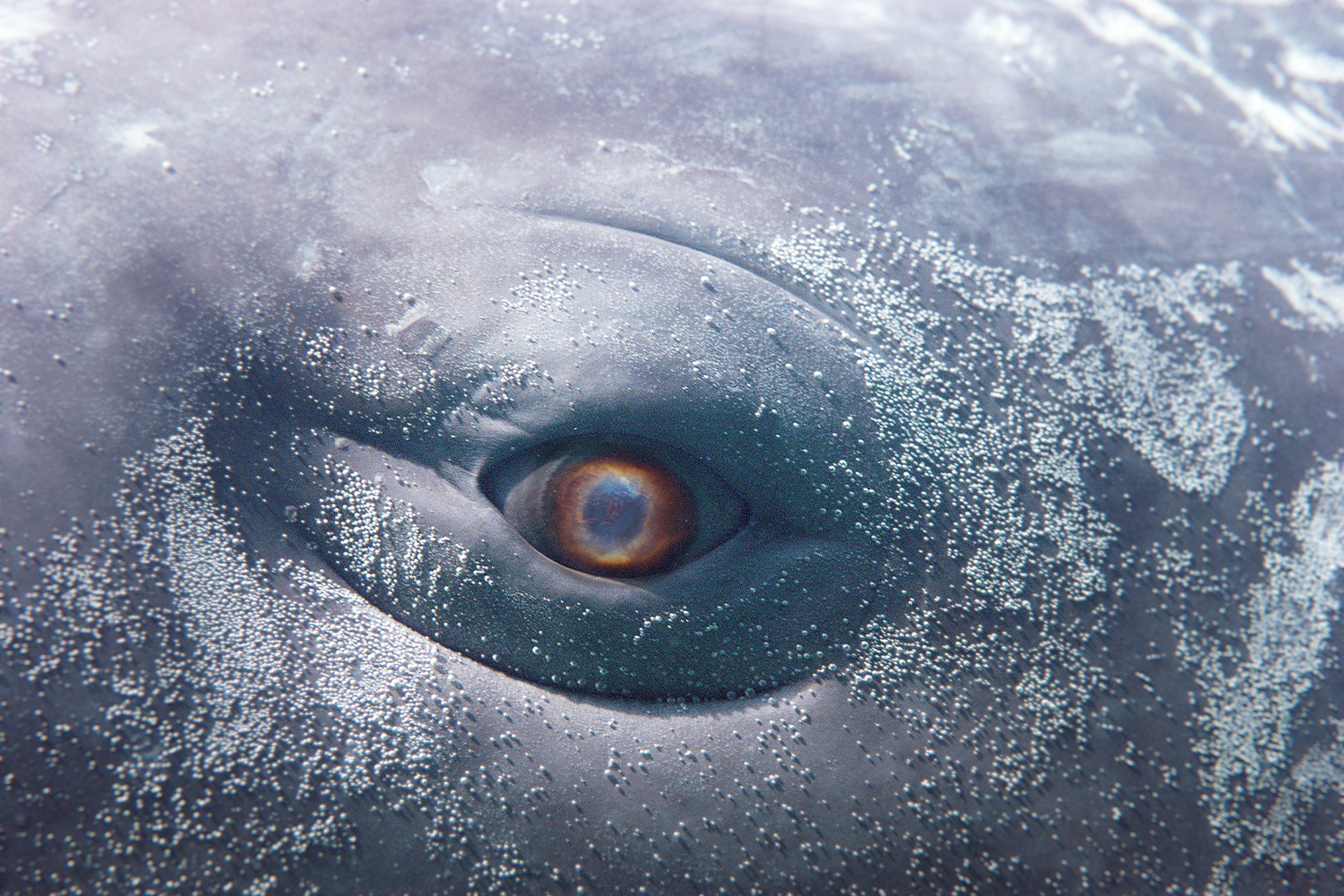

And then with Of Whales, the VR piece that I made in Venice that grew out of both of those other projects, it was the third thing that I did, and it really grew out of my desire to address some of the things that I felt filmmaking as a whole could not address. So with filmmaking, for example, you have a camera and you have “reality” that you’re capturing or you’re staging. And with VR, there’s just so many other possibilities, and also reality is so limited. It’s both infinitely full of potential and also very limited.

And I love that as a form for Moby-Dick, because in a way I think Melville’s book is a VR game. It’s that coded and dense, and also limited in its construction of world. And so, I thought it would be appropriate as a form, especially since I had been working with VR for the making of Moby Dick. I decided that I want to just take it this next step. With the VR piece for the headset, it’s also taking it another step in the direction away from filmmaking and more towards something like an experience. I think one thing that’s probably a through line for all of these works is really trying to interrogate the idea of perspective. Like, I feel cinema has all these historical tropes of perspective, how you’re already constrained by the expectation of perspective, how that’s shaped by the camera lens and also by editing. And in the Venice installation, the concept for me was the perspective of the whale. However, I also feel like it’s an impossible perspective because I’m a human. I think we can’t actually in imagery create the perspective of a whale because they see primarily through sound. The role that sounds plays in whale comprehension — there’s been enough research about that to know that to be true. So, sound plays a big role in the Venice installation as well. And so, if anything, I think I was inspired by the idea of world-making that Moby-Dick has, which then felt really appropriate for a project in VR. And yeah, it’s a very new medium for me. So I feel I’m still discovering what I want to do with it.