In Paul Verhoeven’s film Elle (2016), the main character, played by Isabelle Huppert, runs a gaming company. At a meeting, she scolds a programmer because the orgasmic sounds emanating from a female character onscreen “are way too timid!” This kind of knee-jerk misogyny and violence does not reflect the caliber of video games selected for the exhibition “WORLDBUILDING,” on view at Centre Pompidou-Metz (through January 15, 2024), curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist. This exhibition — which Obrist also organized as a separate showcase in 2022 to celebrate the fifteenth anniversary of the Julia Stoschek “time-based art” collection in Düsseldorf — examines the way contemporary artists use technology and gaming as a mean of exploring aesthetic panoramas, existential anxieties, and sociopolitical malaise. Here, gaming transcends mere entertainment, offering unexpected and even utopian alternatives. “It’s not about tech entrepreneurs who want to go to other planets; it’s very much about what is happening here and how we can make earth a better place,” Obrist says. Games enable artists to “create new worlds, not just inherit existing ones.” These games are “mission-driven” and “empower in a real, concrete way.”

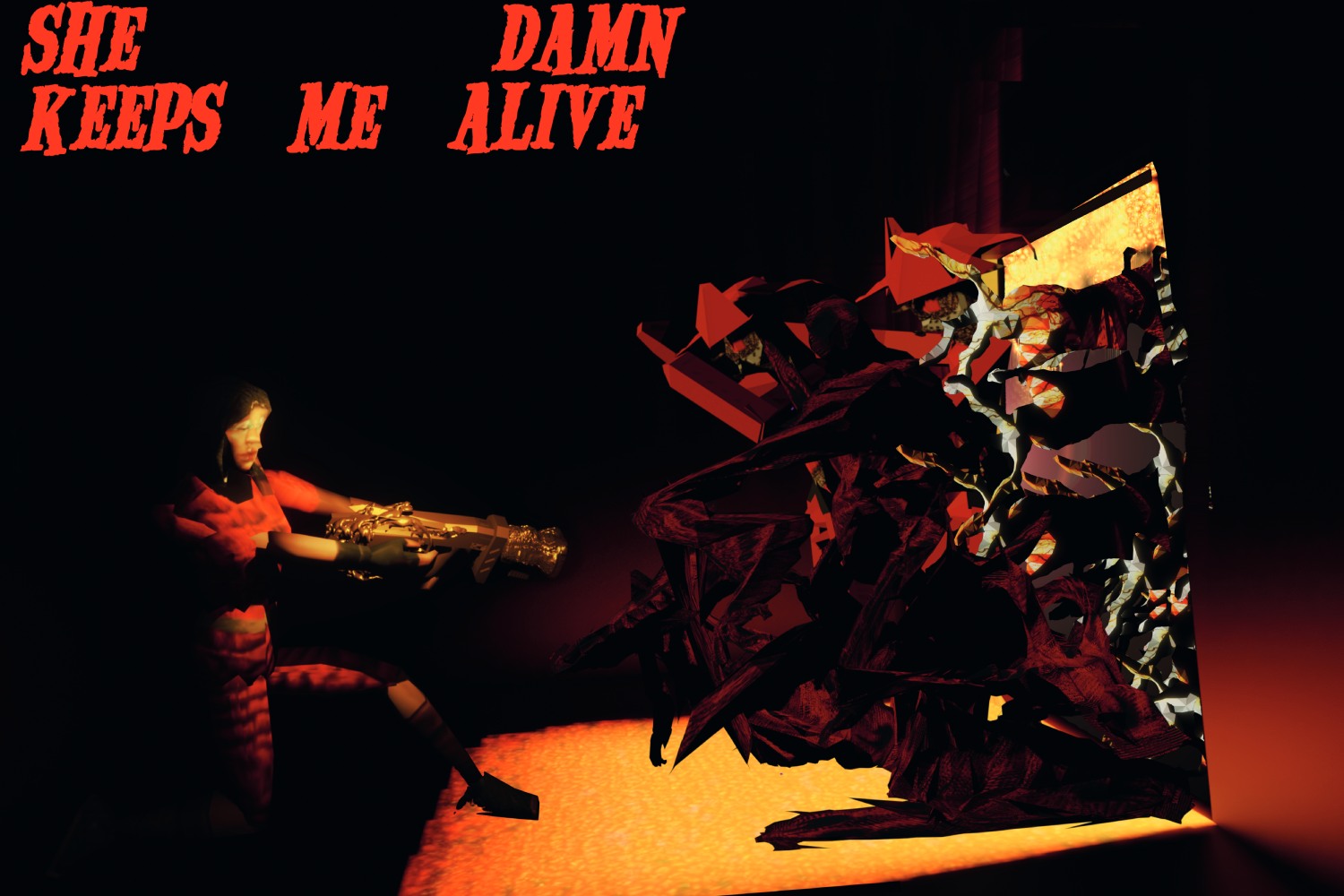

The exhibition encompasses a range of approaches: some artists channel their thematic signatures into game-influenced videos, others alter or disrupt pre-existing games, while others still create fully functional pioneering games. The selection of works is global in scope and spotlights not only a wide-ranging new generation but innovative precursors, notably British programmer Suzanne Treister’s interactive CD-ROM; the Dutch collective JODI’s hack into the game Quake to make it resemble abstract art; and Cory Arcangel’s cheekily stuck-in-purgatory Super Mario Brothers. Some artists present video works alongside installations, like Danielle Brathwaite- Shirley’s She Keeps Me Damn Alive (2021). There’s a game — in which a pink gun can be used to shoot figures deemed threats to the Black trans body — flanked by textile-covered sculptures sprouting screens that present assorted characters (linked to body hair removal and white supremacy). Mimosa Echard’s Sporal is both a game and a canvas. The game is based on a unicellular organism created by the artist: she summoned three gamers to record themselves playing Sporal on the streaming service Twitch. The viewer watches the faces and comments of the gamers as much as the game, highlighting the connective component of how gaming brings people together in a virtual coterie. Adjacent to these screens is Sporal (dôme) (2023), a composition made up of beaded necklaces, fake nails, plastic bracelets, and patterned fabrics. The relationship to materiality is taken a step further in Jonathan Horowitz’s Free Tech Store (2023) an open space in which people can pick up or drop off old tech equipment. His installation reflects how today’s shiny device is tomorrow’s detritus: the Free Tech Store ’s contents remained relatively unchanged over the course of the exhibition, despite the potential for the circulation of gadgetry.

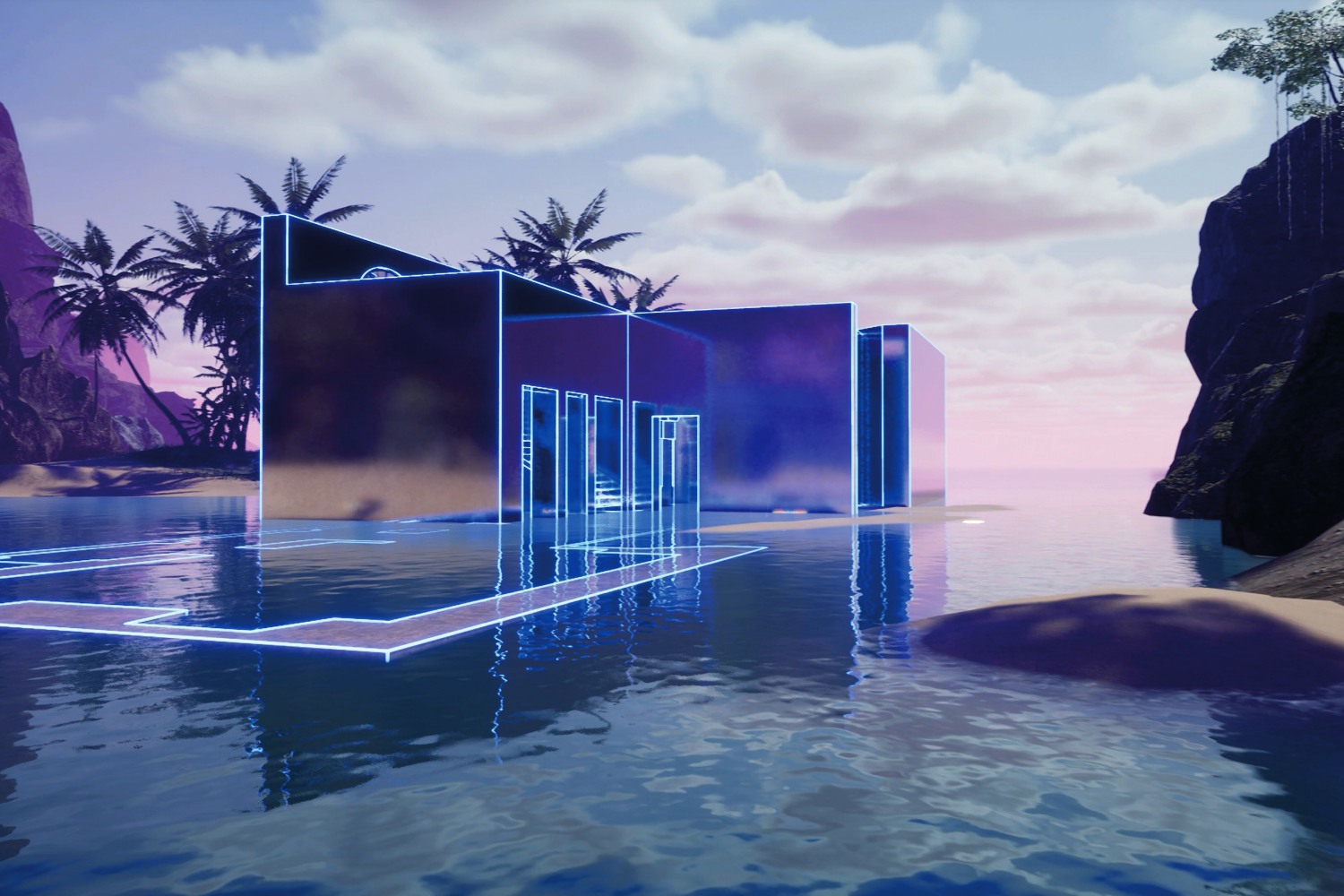

The most immaterial counterpoints to these works are the two VR pieces: the collective Transmoderna created a beautiful experience with their eight-minute Terraforming CIR, featuring a future planet with fiery-red skies and shimmering waters through which nonhuman formations roam, while Jakob Kudsk Steensen’s eighteen-minute RE-ANIMATED (2019) is based on an extinct Hawaiian bird given a “regenerated” existence amid the three-dimensional scan of the surroundings it would have inhabited, modulated by the breath of the participant.

Offsetting the in-person experience, “WORLDBUILDING” also includes an online component; scanning QR codes in the exhibition space yields plenty of take-home possibilities. Ian Cheng’s digital simulations with BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–19), for example, have long preceded the exhibition and have allowed players to influence this character’s “cognitive development” via an app that feeds it various stimuli.

Last year, it was calculated that more than three billion people — over a third of the world’s inhabitants — are gamers. Gaming is a veritable pillar of contemporary culture, one Obrist equates as a deeply interdisciplinary — text, music composition, architectural infrastructure — form of “ ballet russe.” He adds: “there’s going to be so much more, we’ve only just begun,” because gaming’s evolution “is a living organism based on a feedback loop — it’s never really finished.”