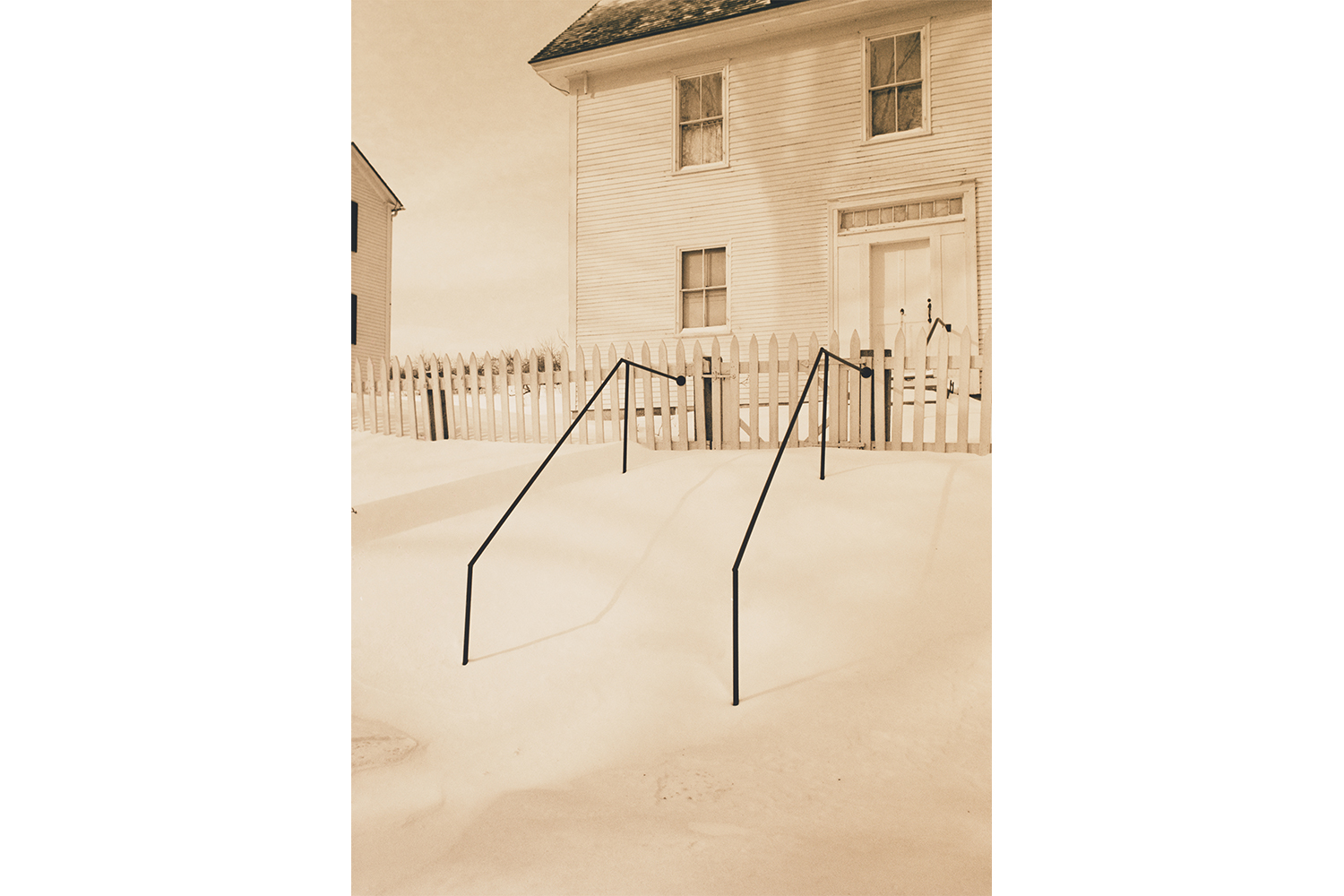

Chance is banal. Immaterial. While it just so happened that photographer Wolfgang Tillmans was a teenager in the mid-sized West German industrial city of Remscheid as the “End of History” made its final approach, it was luck that led him to a copy shop with a Canon NP-9030 laser printer, an unusual machine in that it converted the source image into a digital signal which could then be further altered by the user. Variations on this procedure yielded Approaches (1987–88), a series of xerographic triptychs blown up by four hundred percent that formed the material for two solo exhibitions in Hamburg — his very first — at a popular gay and lesbian bar, Café Gnosa, and Fabrik Fotoforum in February and September 1988, respectively. Only then did Tillmans purchase his first camera — a 35mm Contax single-lens reflex, a simple, robust tool — though this was by no means his first encounter with the photographic device. Critics and the artist alike regard an abstract self-portrait made on a family holiday on the beach of the Atlantic coast of southwestern France — Lacanau (Self), 1986 — as his first “true” image, and even long before then, as a child, he pored over his father’s camera, holding it steady at the eye of his telescope in attempts to capture the patterns of the stars in the heavens. The same telescope was used by the artist to reproduce the twice-in-a-lifetime phenomenon of Venus traveling between the Sun and the Earth, albeit with a new, more sophisticated camera. Venus transit (2004) and Transit of Venus (2012) document the six-hour passage of the gaseous planet (seen in these images as a sharp, stubborn full-stop) before the sublime cutout of the Sun, rendered here a cool, dusty pink against the numbing blackness of space thanks to the use of a Mylar filter. Through the nonscientific and nonchronological results of this work — in some frames, the Sun is nudged off-center, its crisp outline stirred by the artist’s own touch on his equipment — Tillmans’s philosophy of storytelling can be understood as what Durga Chew-Bose describes as “[hanging] on instinct and the rejection of ceremony.” For if nothing else, a photographer’s work is to concede themself to fate, gesture, and all other manners of luck.1

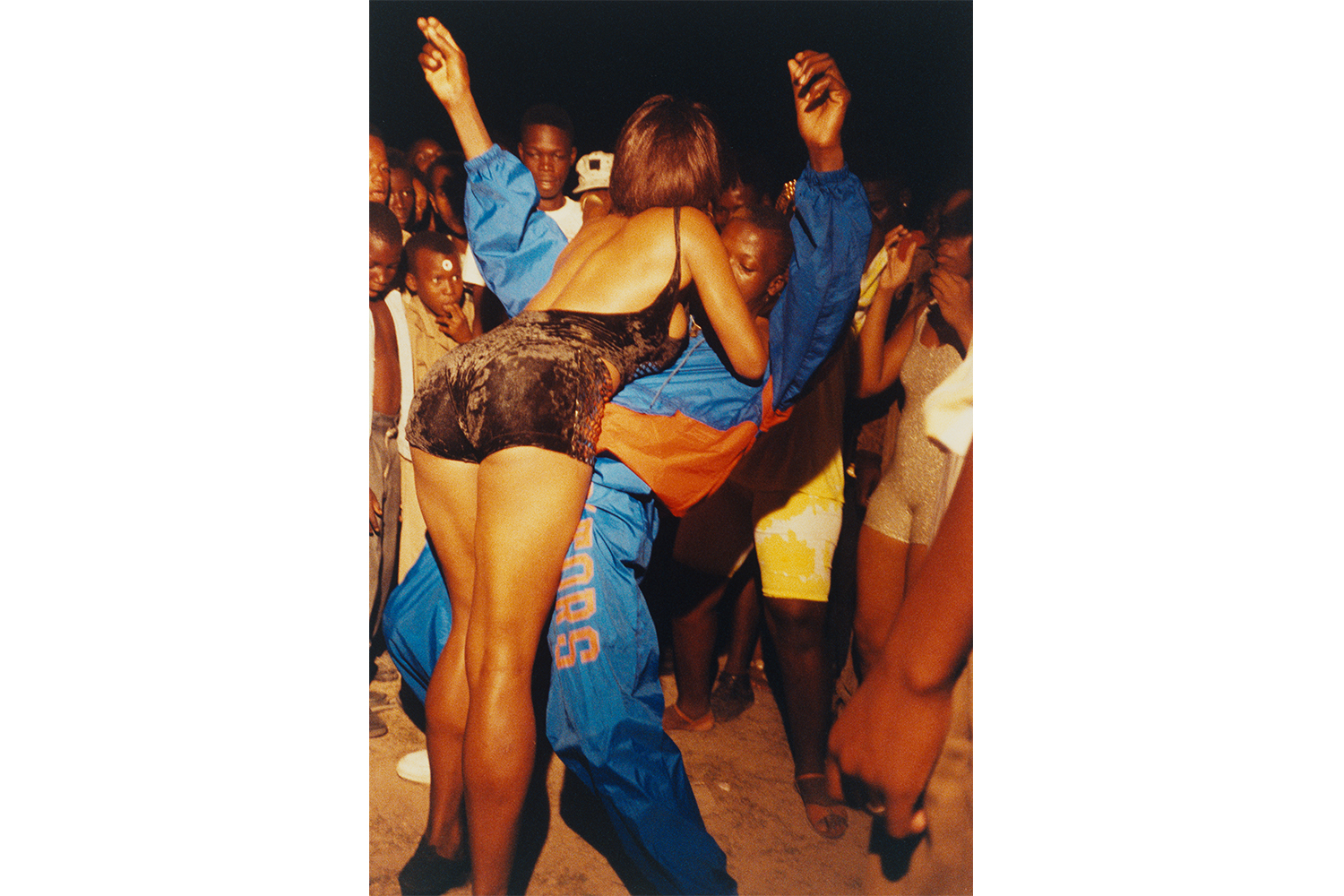

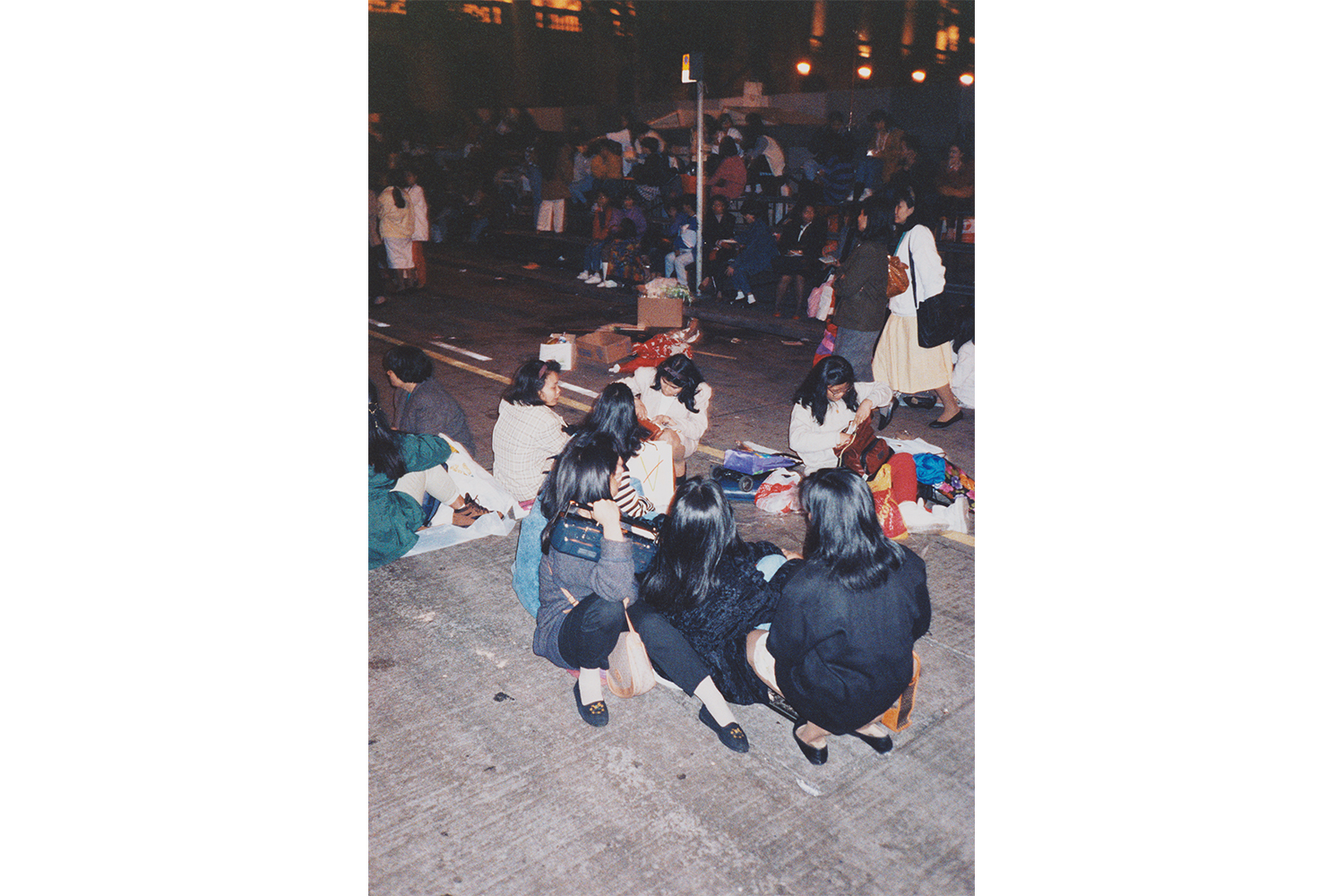

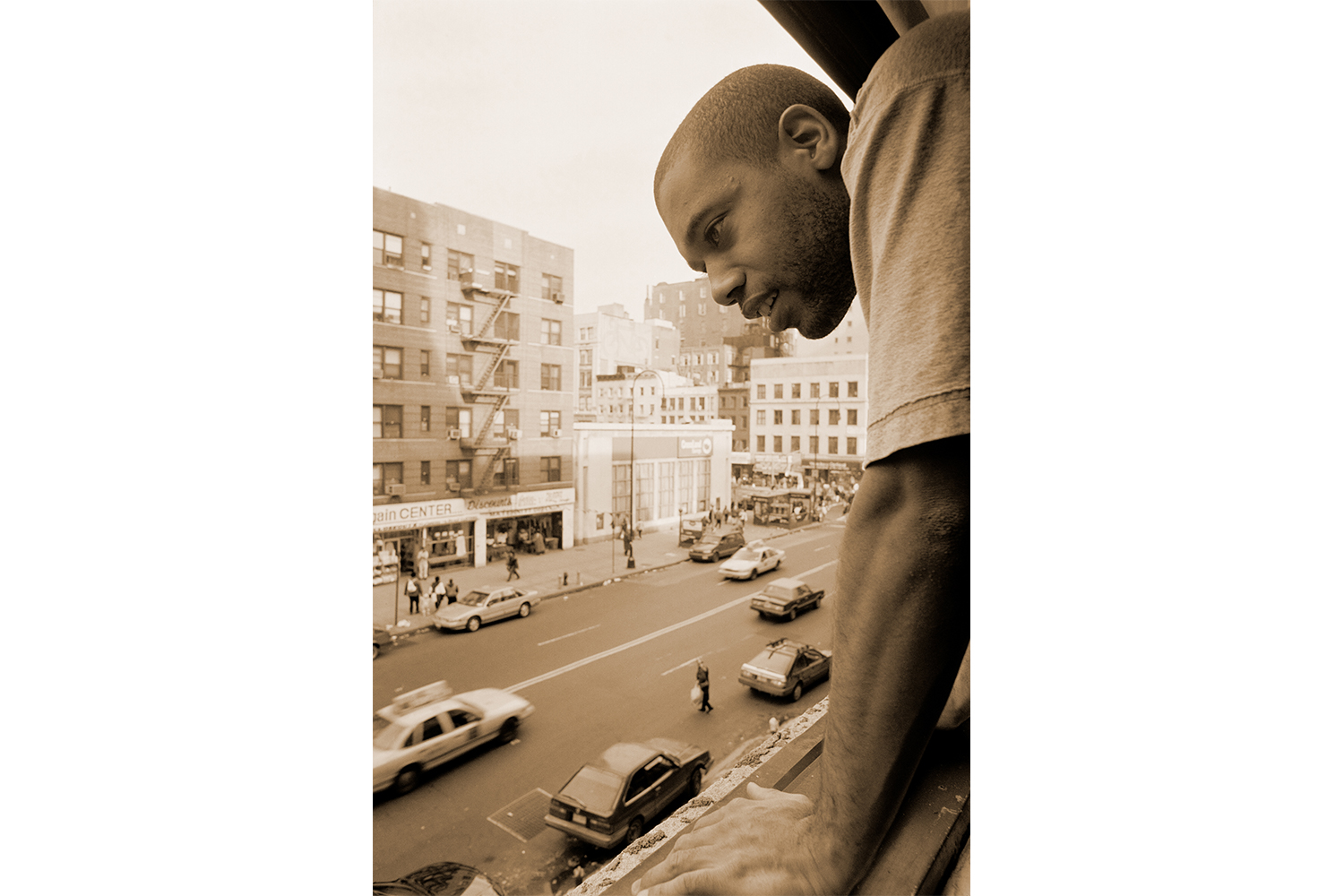

The establishment of the mythos of Tillmans’s early-to-mid-career photographic vernacular can be understood as the by-product of decades of public misinterpretation of the artist’s rigorous curation of his archive as a spontaneous aesthetic, or “the aesthetic of the snapshot,” as his work has been blindly termed in the face of the historic Tumblr (and subsequent Instagram) era. As was made clear in 2003 with the publication of a Tate Britain catalogue of a selection of more than two thousand of his images as thumbnails, carefully arranged in chronological order, as well as with the artist’s own on-record statement, his recurrent point of departure is the single image — an image that is self-sufficient and attempts to challenge its condition of singularity as a standalone work.2 One could be forgiven for tarring all Tillmans’s photographs with the “snapshot aesthetic” label given his emergence on the scene as a flashgun-wielding nightlife photographer for iconic youth culture magazines, notably i-D, for whom he shot his first major story, “Techno is the sound of Europe,” in the clubs of London, Ghent, and Frankfurt in 1991. Moreover, latent episodes of humor and tenderness (mild to explicit nudity of varying degrees of intimacy and sexuality) exacerbate the candidness of the standalone image, notwithstanding the “abyss,” what John Berger described as that between “the moment recorded and the present moment of looking.”3 The stark unambiguity of the printed photographic image does not reside in the instant of the event photographed, Berger explained, but arises in the moment of discontinuity which hints overtly at the distance between the moment recorded and the moment of looking.4 In AA Breakfast (1995), for example, the typically banal punchline of airplane food is hijacked by the image’s subject who clutches his semi-erect penis in lieu of tucking in to his French toast breakfast. Though incongruous, it is just enough. We are not necessarily denied context, just that the context is anonymized. The abyss of not knowing who this person is — if they’re a lover or a friend or a model and why they’re not hungry and why instead they are touching themselves in economy class is exactly where we should feel comfortable. Like a painted still life, the image is sensibly framed and dynamic, and the lack of precedent or antecedent details suggests a sublime moment which just so happened to befall Tillmans’s lens, or so we’re made to feel.

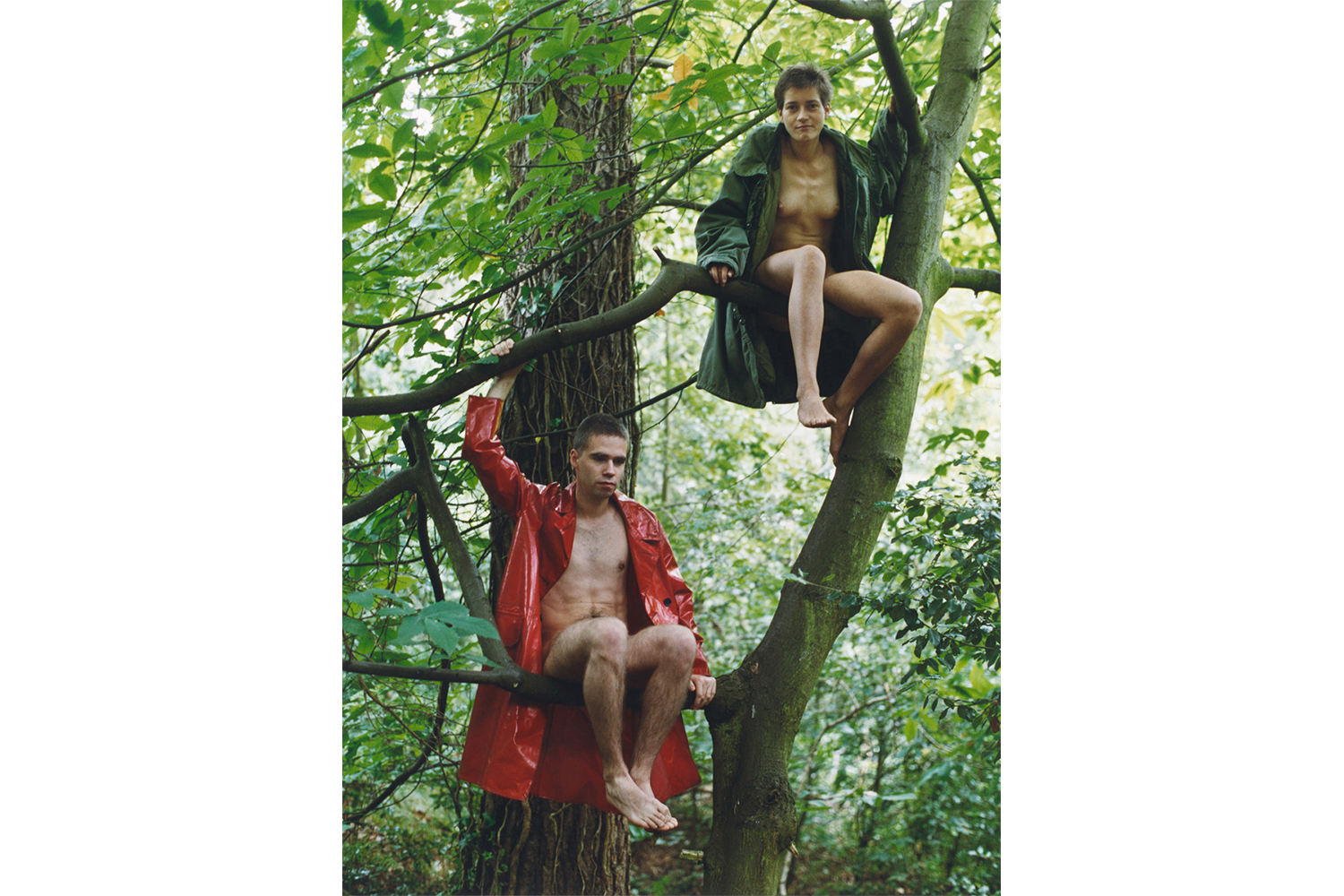

Nudity recurs across Tillmans’s pursuit of the “urban pastoral,” particularly in his images of his friends, the artist Alexandra Bircken and fashion designer Lutz Huelle, who appear portrayed together in various entanglements traversing the spectrum of platonic touch. In Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992), the two appear as described, sitting in a tree, naked but for a red vinyl trench (Huelle) and an oversized green parka (Bircken). “In British counterculture, style magazine pictures are folkloric,” Paul Flynn asserts correctly.5 Since the shoot was commissioned by Edward Enninful for an eight-page i-D spread in 1992, Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees, as well as Lutz & Alex holding cock (1992) and Lutz & Alex looking at crotch (1991), entered the annals of fashion history as art images, being successfully installed on the bedroom walls of androgynous tween wannabes as well as in the white cube. (In 1992, Tillmans hung a print of Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees on fabric from binder clips at Maureen Paley’s booth at UnFair, Cologne, thus inaugurating his signature hanging style of placing large prints as planets around which smaller prints orbit in a proximate and thematic relational hierarchy.)

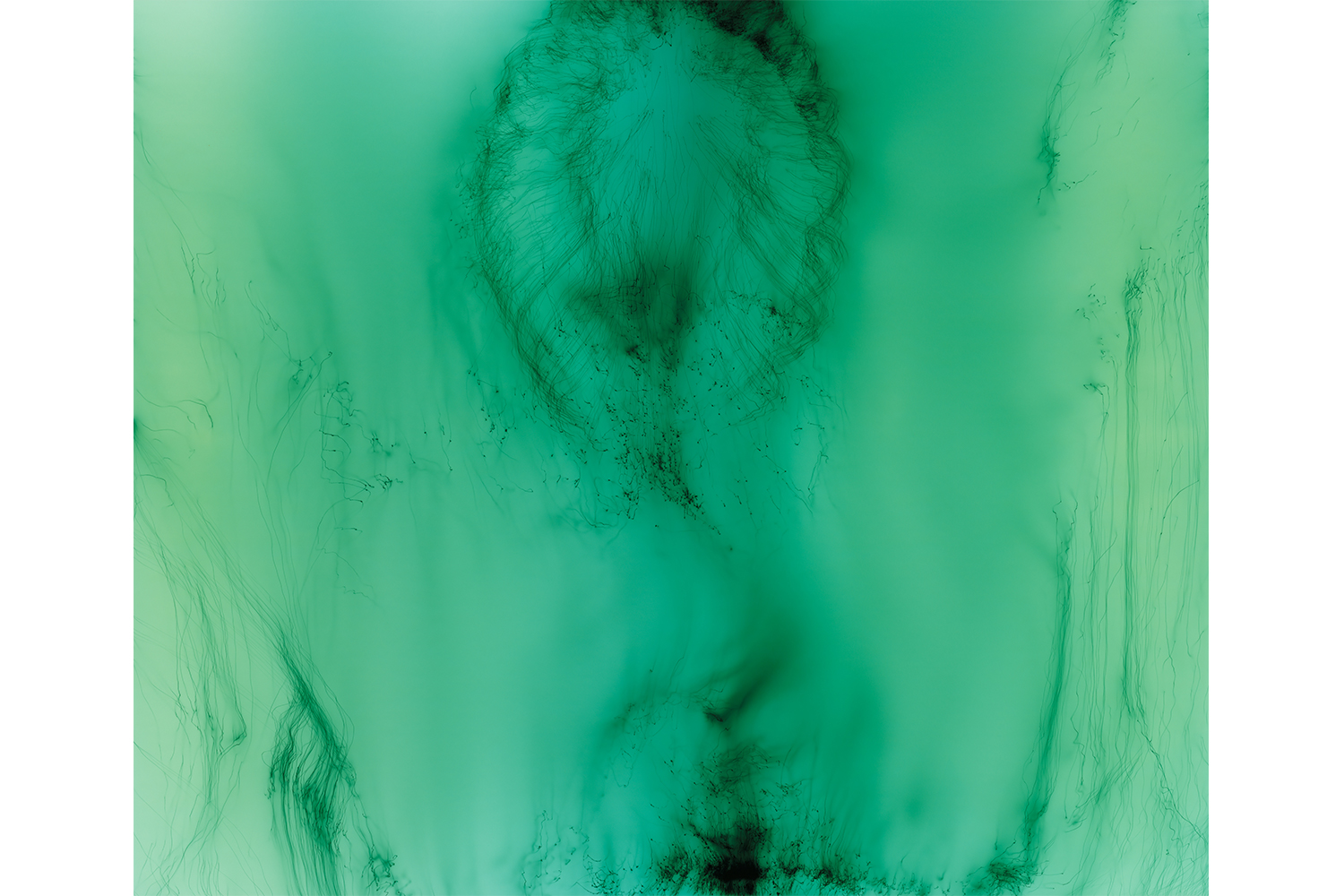

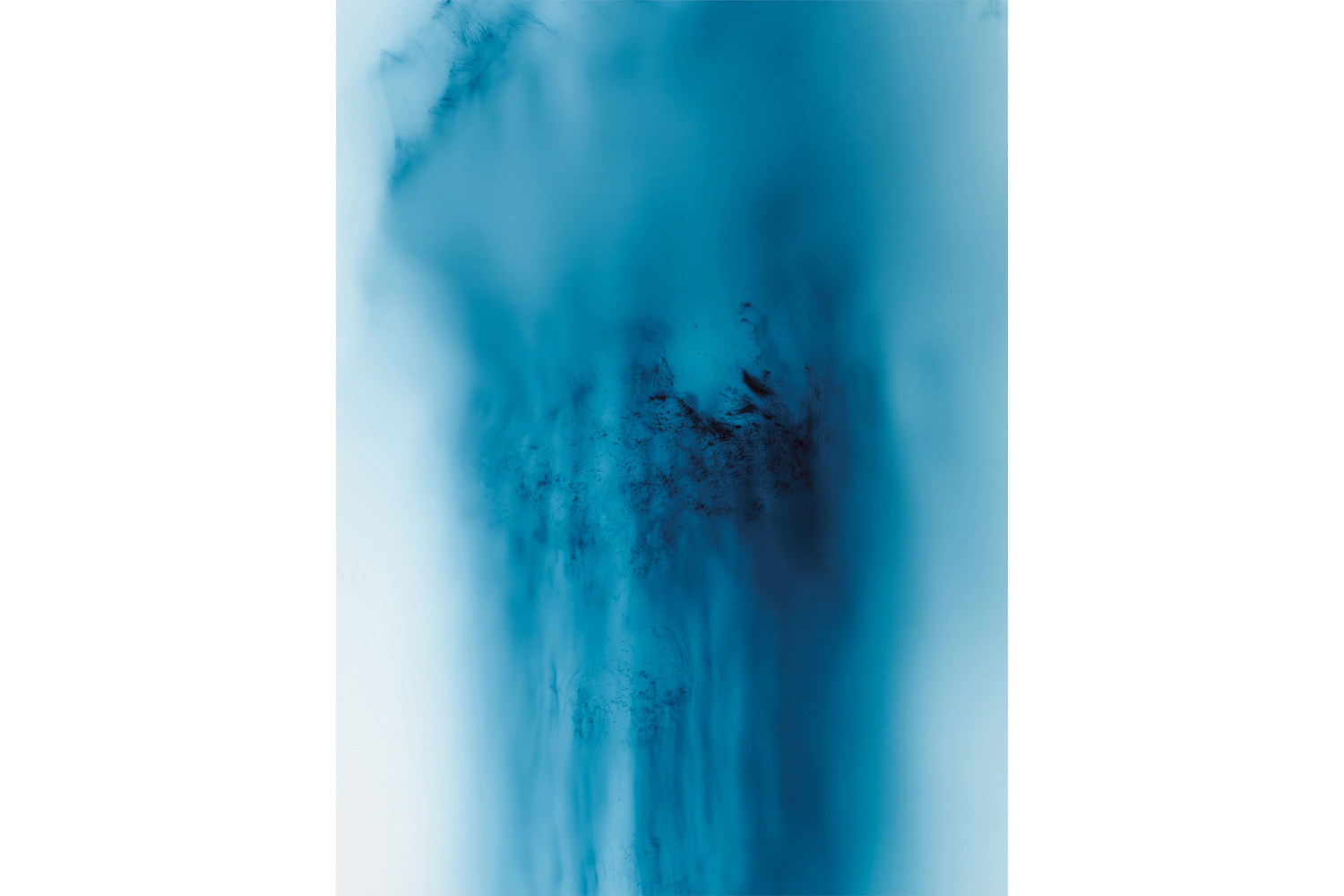

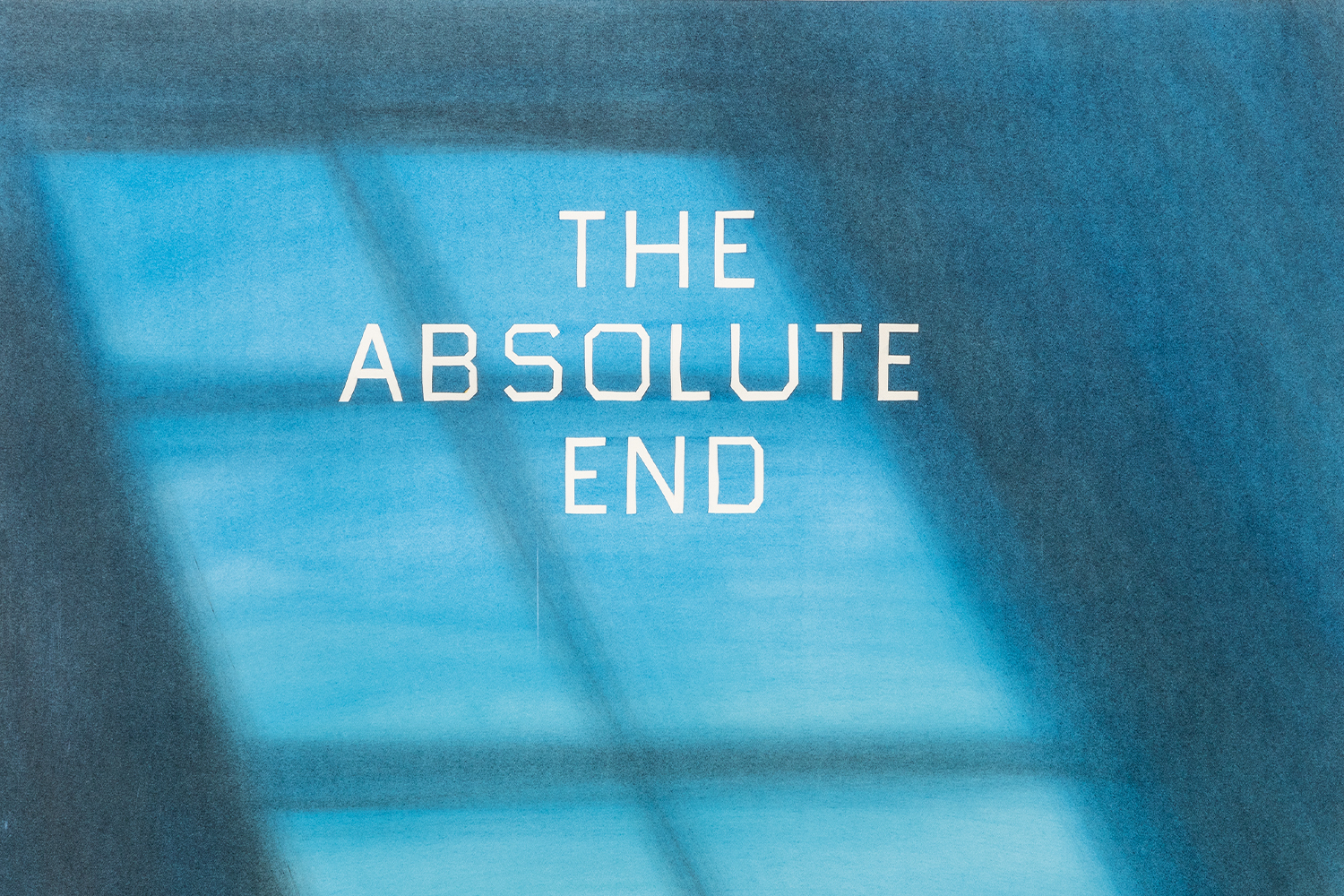

The deft transference of Tillmans’s photographs across the thresholds of intent, desire, and presentational context can also be examined within his works on a meta-level. The post-2000 “darkroom abstractions” exaggerate the gestural relation between the photographer and the final image even when working without a camera, exceeding what he had already demonstrated in terms of his relationships with his human subjects, spurring more dynamic reflections on corporeality and how this might be referenced in the pictorially flat, traditionally developed photograph. The Freischwimmer (2001–4) works potentially explore the object-subject paradigm (the direct relational effect of handheld light sources shone against photo paper and the resultant proof of this effect) to whimsical, color-field-like ends. In a different faction of his practice, the truth study center (2005–ongoing) project calls for the installation of several tables of various heights and sizes to be covered with printed matter and archival material, commanding the viewer to assess the parts of this deconstructed montage and, from that, find truth in opposition to traditional ideologies of knowledge accumulation and dissemination. Most rigorously, with his Soldiers project, a collection of images of enlisted soldiers both in and out of direct conflict compiled over the course of a decade and published in 2000, Tillmans produces an effect that goes against the “typical” experience of his work, what Kodwo Eshun described as an experience of “immediate thrill, of short-circuited hierarchies, of worlds connected, of moments, desires, moods that had never been elevated and valued before.”6 With Soldiers, Tillmans indulges his longstanding metaphoric and literal interests in camouflage via the specific media of images of army servicemen published in the news regardless of the conflict they are embroiled in or the faction they serve. By making the military and the militarization of men the object of his aesthetic observation, the artist presents a critical basis to approach the way war is reported on (in the West) in terms of image vernacular, beyond — or before — the disregarded headlines and articles. Tillmans’s early reverence for the night sky is a favorite anecdote of critics, and for good reason. In his decades-long career thus far, the artist has exemplified through various photographic and creative techniques the many ways to contain multitudes within a single image — how to confine infinity within a dot, the aleph — and further, how to arrange and publish (whether literally, in a book, or within the context of an exhibition, and other means) his works so that their constellatory relation to one another, and another, and another, may rationalize their own subsistence.