—1 —

Is it the end? Has the end finally come? No one is sure exactly when it’s happening. We have waited and waited. A long time now. Our entire lives. We did not know what the end would be like. Could it be here, now?

—2 —

It’s February 24, 2022. Russia invades Ukraine. No, actually, at that point, personification was foremost: Putin invades Ukraine. This signaled a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which had begun in 2014. Putin’s latest attack — and associated rhetoric — came with a scale and force that signaled “History” with a capital “H.”

I had just caught COVID-19 for the first time while visiting my parents in England. My throat swelled up to the size of a monstrous grapefruit, covered in razor blades, and I was confined to my teenage bedroom. I remember it being 2:00 a.m. or so. I hadn’t slept in nights because of piercing throat pain. On Twitter came a live, night-vision feed of Russian troops firing at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. I was aghast. “Who fires at a nuclear power station? Especially at Chernobyl?”

My body was instantly transported back to the mid- 1980s when, at primary school, we would carry out rehearsals of what to do if the Soviet Union fired nuclear missiles at us. Some of you will know the routine: a siren went off, and you had a few minutes to hide under your desk, as if that modest defense would save you from the punishing white heat of the atom bomb.

Watching the grainy, live-feed of Chernobyl in February 2022 — every gunshot registering as a flickering white speck — it felt like the specter of nuclear annihilation was suddenly back, uninvited, having been laid to rest in 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed.

My first thought that first week of Putin’s invasion was, “Is this the End of the End of History?”

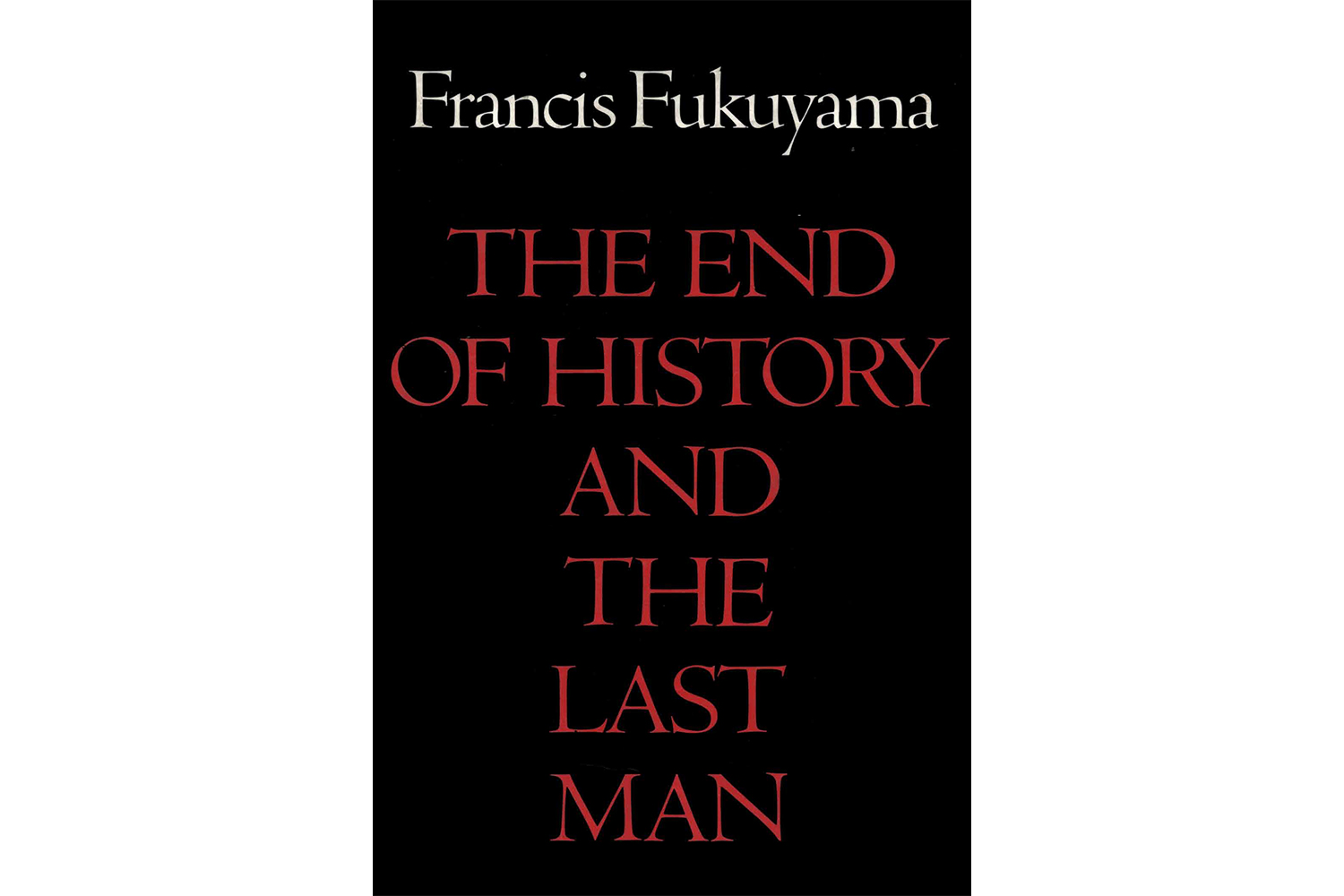

For those of you not familiar with the original version of this phrase — “the End of History” — it was coined by an American political theorist named Francis Fukuyama, first in an essay in 1989, and then in a book from 1992. Its core thesis argued that with the ascendancy of Western liberal democracy — which occurred after the Cold War (1945–1991) and the dissolution of the Soviet Union — humanity reached “not just … the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: That is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

My second thought was, “Is this Endcore?”

— 3 —

Endings may offer the promise of salvation, redemption. Even liberty. But they are also exhausting.

— 4 —

A week before the Ukrainian invasion, an article in The Cut announced that “the vibe has shifted.” One thing we all now seem to feel collectively is that change keeps changing.

If the future is certain, and the past is unpredictable, then the present has become more impossible to predict.

Art movements used to last decades. Now memes barely last days. Memories are either ten minutes or ten years ago. Against this proceleration (the acceleration of acceleration) is the desire to label every micro-cultural moment on the internet, especially on TikTok. Everything is rendered as a “——core.” If it isn’t a ——core, it didn’t happen. Cores are like screenshots as trends. And once the core is indexed, archived — you simply move onto the next one, which will come along later on the same day, probably.

Francis Fukuyama’s Instagram account includes pictures of his drone collection. Shinzo Abe — Japan’s former prime minister — was assassinated in July 2022 in a way and for a reason that didn’t make any sense on the surface. Former British prime minister Boris Johnson had had to repeatedly defend the right to serve birthday cakes at 10 Downing Street during COVID lockdowns. DALL-E and other prompt-generated text-to-image software remind us how we are now just machines that spew up absurd search terms for AI’s amusement. Even NASA admitted they don’t really know what’s going on in the universe anymore. Henry Kissinger — the archangel of twentieth-century hawkish American foreign policy — admitted, “We are now living in a totally new era.”

Slavoj Žižek calls this “hot peace”: “a state of permanent hybrid war in which military interventions are declared under the guise of peacekeeping and humanitarian missions.” Another name for this is Endcore.

— 5 —

When Endcore began, you were reading Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life, where he said, “The slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations… In one very important sense, there is no present to grasp and articulate anymore.”

When global narrative collapse invades our innerspace, do new stories emerge? What if the future is now a thing of the past? Have you noticed how young people seem to wear several items each from a different decade or historical style? The model-activist Bella Hadid is an example of this “Chaoscore,” in which the present seems only to be grasped and articulated via a clash of references and tastes all unmoored from their provenance, falling, like Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920), which Walter Benjamin described as confronting a storm that “irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.” Chaoscore is Endcore’s style du jour.

— 6 —

The same week Putin invaded Ukraine, Balenciaga staged its fall/winter 2022 fashion show. It took place in a gigantic circular panopticon. Models tottered across snow, in stiletto heels, clutching handbags in the shape of black dustbin bags. They looked like billionaire refugees fighting the storms of change. Balenciaga’s creative director, Demna, wrote show notes that linked his own past as a Georgian refugee to the millions being displaced by Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. Dystopian Endcore is no longer just a literary or cinematic genre. It’s a branding language for a multibillion- dollar luxury fashion house.

— 7 —

I genuinely don’t know where my doomscrolling ends and where I begin.

— 8 —

The End of History, as an argument, emerged from a bipolar, Cold War, twentieth-century world where the USA vied for global dominance with the Soviet Union. But in the ensuing future since 1991, since 9/11, since the global financial crisis of 2007–2008, it is the rise of China — economically, politically, technologically — that has challenged the USA’s unipolar status in ways that Fukuyama did not seem to fully account for back in the early 1990s. China’s robust economy became turbocharged over the last four decades without adopting parliamentary democracy. China became a poster child of what one could call “state capitalism,” a system that has produced several national examples of economic growth without the concomitant need to adopt Western-style democracy.

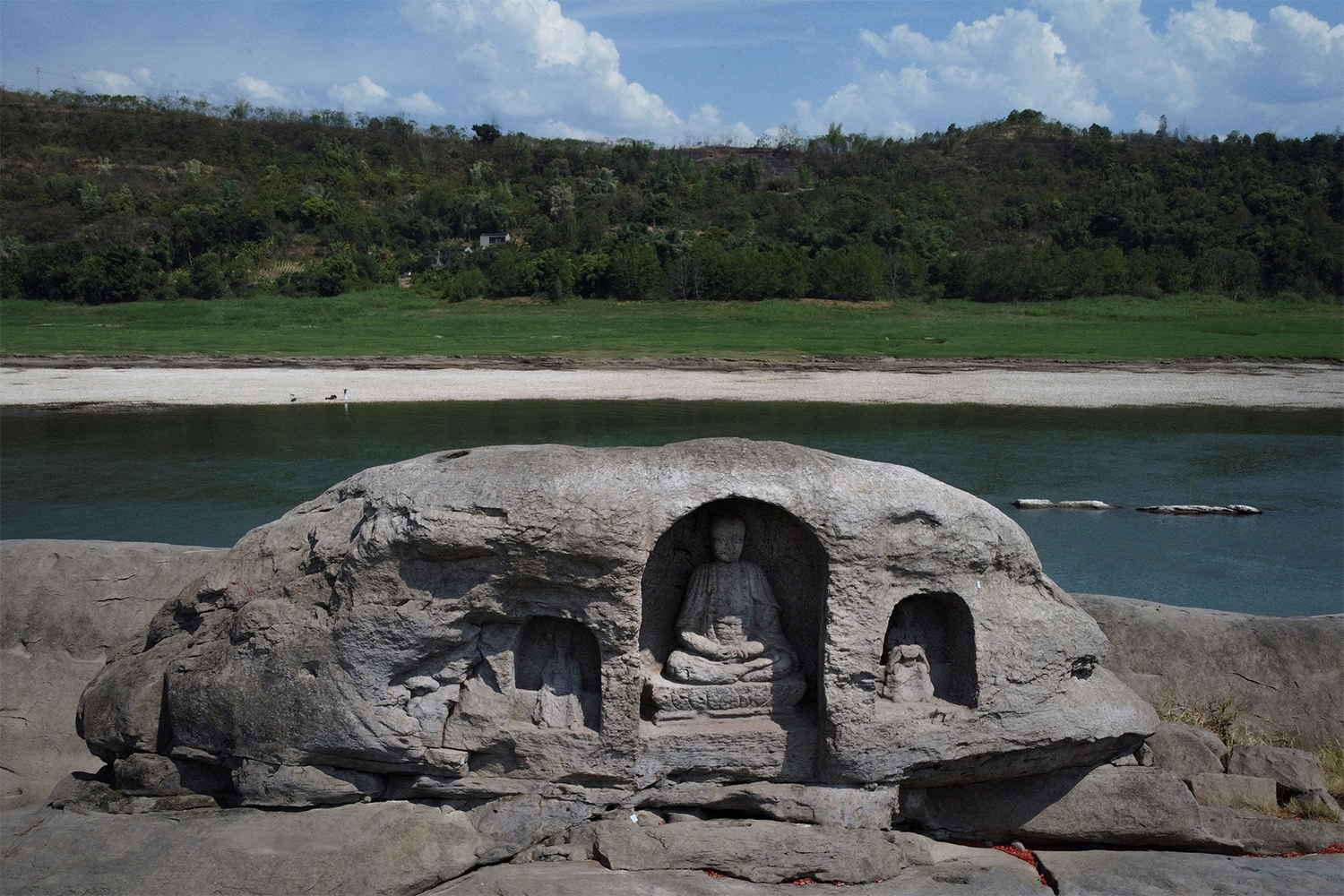

I wonder how the End of History looked from China’s perspective? Now that President Xi has ensured another term of power, the likes of which have not been seen since Chairman Mao, is history — with Chinese characteristics — just starting again? Or is Xi’s determination to effect a “zero- COVID” policy throughout China the end of the “Chinese Dream” that for so long seemed to shift the world’s gravitational center Eastward?

— 9 —

In September 2022, China discovered a crystal from the moon made of a previously unknown mineral, confirming that the lunar surface contains a key ingredient for nuclear fission, a potential form of effectively limitless power. This story fulfils many criteria of what made twentieth- century sci-fi so compelling. Endcore may signal the end of human life on Earth, buts is it also the premise for human — and augmented human — life elsewhere?

— 10 —

Multiverse theory postulates parallel universes — less alternate histories, more maximalist presents — where everything that could happen is happening simultaneously. The film Everything Everywhere All At Once became an unpredicted hit in the summer of 2022. In it, the story of a Chinese immigrant struggling in America — with her business, her husband, and her daughter — is told through a series of zany multiverses. The viewing experience is chaotic but also oddly realistic feeling. Endcore is an endgame, an aporia. If optimism is impossible in our storyline, the one we seem to be living in, then why can’t we travel to a multiverse where there’s no Endcore? Where climate grief never happened? Where there’s no microplastics in the Antarctic snow? Multiverses have invaded popular culture today because they offer an escape from Endcore.

— 11 —

We recreate the horizons we have abolished, the structures that have collapsed. And we do so in terms of the old patterns, adapting them to our new worlds.

— 12 —

I didn’t want to end I’m Thinking of Ending Things — Charlie Kaufman’s last feature film, released on Netflix — because I wanted to stretch out every affecting, truth-tinged moment. In internet speak, this is akin to “edging,” when you elongate pleasure, defer climax. It’s something I rarely feel with newly produced culture. The allure of scrolling for something better, swiping for someone hotter, has destroyed my attention. Yours too, if you’re honest. A few hours before I watched I’m Thinking of Ending Things on an airplane, during the autumn of Year One: Coronacene, I had been at my parents’ house, preparing to say goodbye to them. The pandemic made planning the future inevitably uncertain. We didn’t know when we would see each other again. My father is in his mid-eighties, and his body visibly carries time’s passage now. He and my mother had their backs turned to me, in the kitchen, facing the fridge, and, for this split second, it was as if this image of the two of them turned into an image for forever: for when they aren’t here, for when I am not here. Like the image that haunts the protagonist in Chris Marker’s La Jetée, or the one that plagues Dom Cobb in Christopher Nolan’s Inception. During Endcore, I feel these images more and more: how the present feels from the future, a retinal engraving, haunted and haunting.

— 13 —

I was a guest on the New Models podcast with art writer Dean Kissick. I blurted out the phrase, “the end of the end of history,” and one of the co-hosts, Lil Internet, replied, “like History 2?” Umpteen DMs later, we collectively decided that the way to spell this neologism is HSTRY2, adopting that recent branding vogue of eliminating vowels. HSTRY2 is history’s sequel — or prequel, or reboot, no one is entirely sure. But we do know it’s a revenge of HSTRY2 on History (with a capital “H”), set to an erratic, broken laugh track. HSTRY2 trolls us. HSTRY2 is the illusion of the new world about to happen at the dawn of Endcore.

— 14 —

I promise you it’s nearly over. I promise you this time it’s true. I promise you we’re in the Endcore now.