“Now” is already too late and, in its lateness, a lie: the utterance of now is a now no longer. It furnishes instruction as a mere introduction: “now, then.” It precedes action with a dragged exclamation: “now or never!” In search of a time that it itself has lost, the now never quite snags the trueness of itself, a wrinkle, a stagger; its failure edifies only that its moment was an afterthought. Shadowing this inevitability, Win McCarthy’s “now” is also a time live buried. They say a day seized is a day well spent, but McCarthy’s “today” is a whole reality that’s already slivering from view, tired and truly spent, mildewed by the creeping onset of “tomorrow.”

The dawning dereliction of assigning the present before it becomes the past installs an ordinariness within McCarthy’s project of expanded self-portraiture, where the self treads the expectancy of collapse. In this temporal lag of a pendant present, other kinds of dialectics are limned, between self and stranger, singular and common, interior and exterior, their descriptions stalking diminishing thresholds. While these distinctions might overlap or interfere, they more often proffer an aporia of language. Grasping and glimpsing, McCarthy’s labor on subjectivity is both diligent and desperate. Through sculptural work mingled with writing, photography, and drawing, his chronic pursuit of clarity in memory, embodiment, and perception leaves a trail of fraught parsing and silhouetted seeing. Hard terms of interrogation, including the desirous, diminished, or dispirited “I,” lose their edge in a long black procession. Boundaries are slenderized to their limit in a grammar of glints, edges, dashes, and scrubs. Routinely skewering and reshaping intimacy in ways like love or a terrible crush: Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose.1

Sleuthing McCarthy’s mind sees reflections on intimacy and interiority enter hypnagogic egressions, foreshadowing evaporation. With lyrical exploration of his anxiety, a narrativized approach to autobiography magnifies the diminuendos of New York’s daily grind — McCarthy was born in Brooklyn and has lived there ever since. Gravity spikes the quotidian, gilding things briefly. Specifics blear into bewildering vapor. At a fevered tip of psychic travail, the pitch of McCarthy’s work is exaggerated by the confessional and attenuated by excessive analyses. If human beings are “great dreamers of locks,”2 McCarthy’s confessional mode is a superabundance of transparency. Most lucidly asserting dislocation or disappointment, his writing emanates Romantic overexposure that widens into obscurity, where the projection of an expressive voice dissipates the contours of its individuality. With melancholic examination as a dominant register, these habits of reasoning seek to reconcile the dissonance of the fact of oneself against the fact of the world, where all around people seem impossible. Lack, then, is both crisis and crux: “The truth begins to feel like a hole,” he writes, “an empty volume with mass enough to create pull, like the seductive gravity at the edge of a rooftop or a balcony.”3 A “practice” in its truest sense, McCarthy’s preparatory and provisional work ensures that the temporal phenomenon of crisis — a decisive point that alters the understanding of before and after — rarely, if ever, arrives. Then again, when is a crisis of self in time ever over?

Puddle, pothole, portal, person, persona, passerby. Between conception and realization, smears of plasticine and resin formed McCarthy’s early self-portraiture. Exhibited in “Mouth, etc” at Off Vendome, New York (2015), the surfaces of these shallow reservoirs contained outbreaks of textual jetsam, their skittish thinking expressed as melodramatic scrawls or schematizing annotation, issuing a mulch of indecision. In Diagrammatic (2015), a circle enclosed the words cheek; chin; eye; eye; nose; stubble; stubble; stubble; mouth, etc. each arranged in the place of those respective features. The blunt facticity and anonymizing reduction of these labels press upon the limitations of imaging the self, as though the most basic language could substitute a face. Similarly, in Some Cheap Mask (2015), a taught scrim of plastic sheeting used to package artworks became an empty cover detailed by tiny eyes and mouth cut out from photographs. An interstitial skin nakedly displayed, here was a self of disquieting thinness bared to gimlet eyes: There’s literally nothing to him! He’s so transparent! This was self-portraiture that began with losing face, qualities sloughed to invoke a more elemental constitution, as if such a self-archaeology could pronounce the closure of an essential, lustered core. As if, indeed.

In these early works, McCarthy’s “I” stands for “Intruder,” one who is “wearing my face like some cheap mask.”4 A series of glass masks involving casts of the artist’s face, dilute identity in the presence of the face and its immediate effacement. The process of casting begins with precision, but in the pliant materiality of glass, such details portend to slacken or crack. As a result, these masks — exhibited in his solo exhibition “Mister” at Berlin’s Silberkuppe (2017) — have a dubious temper and near throwaway construction that, without courting sympathy, makes them fundamentally vulnerable. Rigged to the wall by shoelaces and with bodies drawn by wooden canes, some of these works assume personability on a first-name basis: Imogen (Blue World) and Chris (both 2017). “Specifically me, and generally human,”5 these masks adhere to the notion that one is a confluence of others — the self as collaboration, as disintegration — reflecting a self-portraiture that has been proxied, emaciated, worn out. These regions of the represented face, with its inexorable return to the unfathomable conditions of subjectivity, stalk the border of a recognizable “someone.” If the territory of the face is both the most abstract and the most concrete site of recognition, these are facilities that exalt this very problematic. Between mystery and system, these masks know that the face is already overdetermined, a “white wall/black hole system”6 following Deleuze and Guattari. Half-conscious, half-signified, this face a mutated offspring that, firstly, “constructs the wall that the signifier needs in order to bounce off of […] the frame or screen.”7 Secondly, the face “digs the hole that subjectification needs in order to break through; it constitutes the black hole of subjectivity as consciousness or passion.” 8 Territorialized and indexed through regimes of representation and identification, the face over-codes the subject: “You don’t so much have a face as slide into one.” 9For McCarthy, such “familiarities” are foiled half-truths, borderline fictions. Yet, however real we pretend to be, it is this “human” face, expressed through the dissensions of dark and light, that allows us to get up and, ugh, face the world.

“Memories are motionless,” Gaston Bachelard writes, “and the more securely they are fixed in space, the sounder they are.”10 Using rudimentary models for measuring, organizing, or assembling, McCarthy arrays “architectures of interiority”11 that plot the suspected whereabouts of recollections. Templated systems of floorplans, maquettes, calendars, and lists are atomizing scaffolds or precarious containers, each chronicling the self as coterminous with the space that surrounds it. Within New York, then, the city’s development and demolition affirm that the uncannier decrescence, construction, and maintenance of the self will be a work in progress and possibly more easily erased.

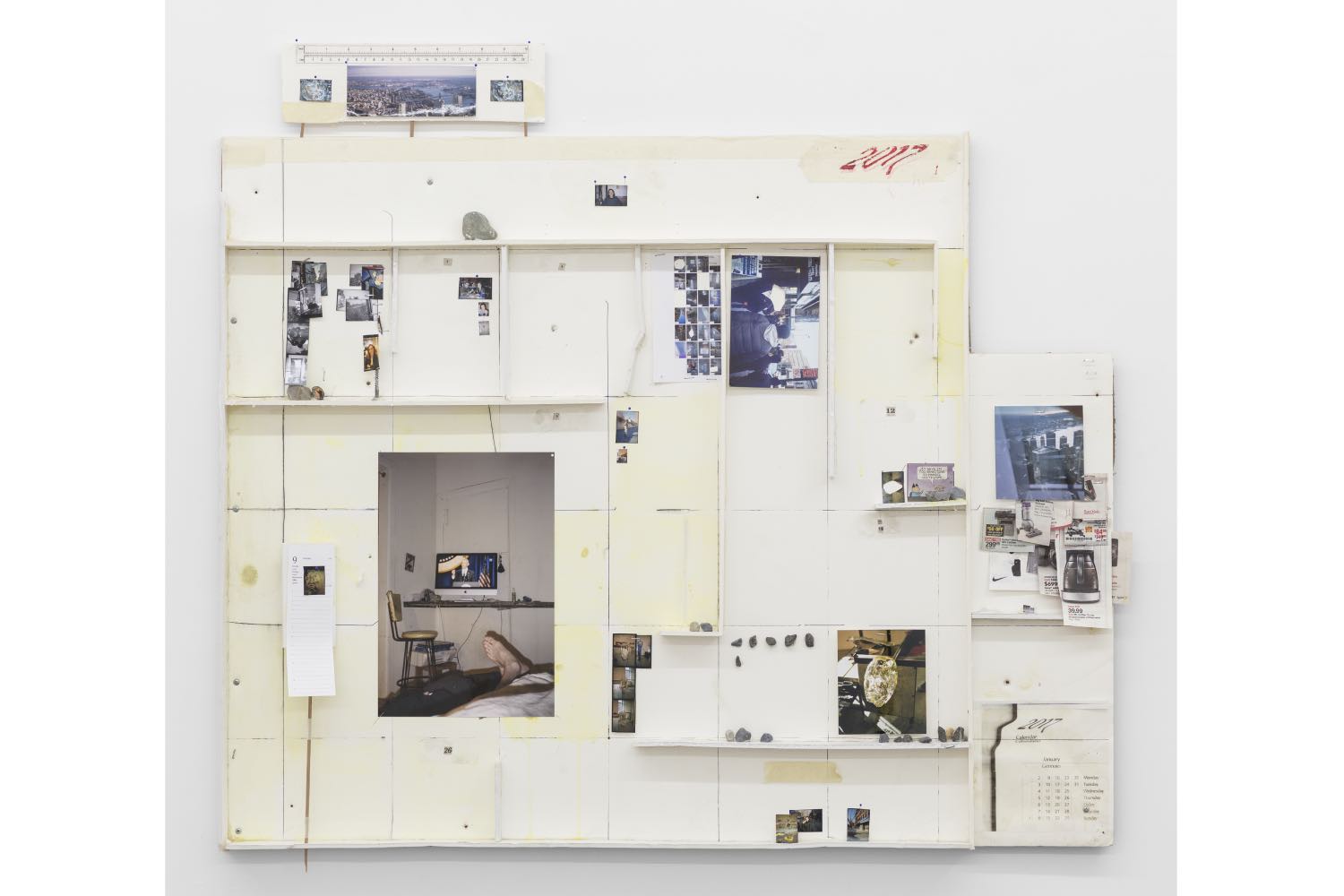

With the granular banality of dailiness, McCarthy grazes the impossibilities of time. Such instances are ever partial: “always these few raindrops and / never the storm —.”12 In January ’17 calendar (Der Fuß des Künstlers) (2017), a lightly penciled grid on foam board presents the suggestion of a calendar either disassembled or yet to be filled. Tacked about are little bits of trace: lined-up pebbles and scissored coupons, snapshots of friends, the glass casts, and the New York skyline. Monday, January 9th, is a molten face of total gloom. Some weeks create shelves to shoulder a burden while other days loom larger. One photograph shows the artist’s bare foot in bed as he watches Obama’s State of the Union address — the awkward, inexpressive anatomy of the foot a base witness for “world events.” In March ’17 calendar (bits and pieces) (2017), diaristic snapshots populate the periphery of the sketched grid, awaiting attribution. While these photographs attempt to coarsen memory as evidence, here they rest as lines drawn in the shore. As renditions of the “now” get shelved into “then,” these cartographies of who knows “when” digress and fester with an almost cryptographic despondency, giving perfectly pathetic form to the insurmountable task of assembling a past. The promise of reduction’s perspicuity — its ruling of this or that, good or bad — becomes blighted by affect, the misremembered, the unsaid. How to preserve the invisible if it can only be measured against the advent of disappearance?

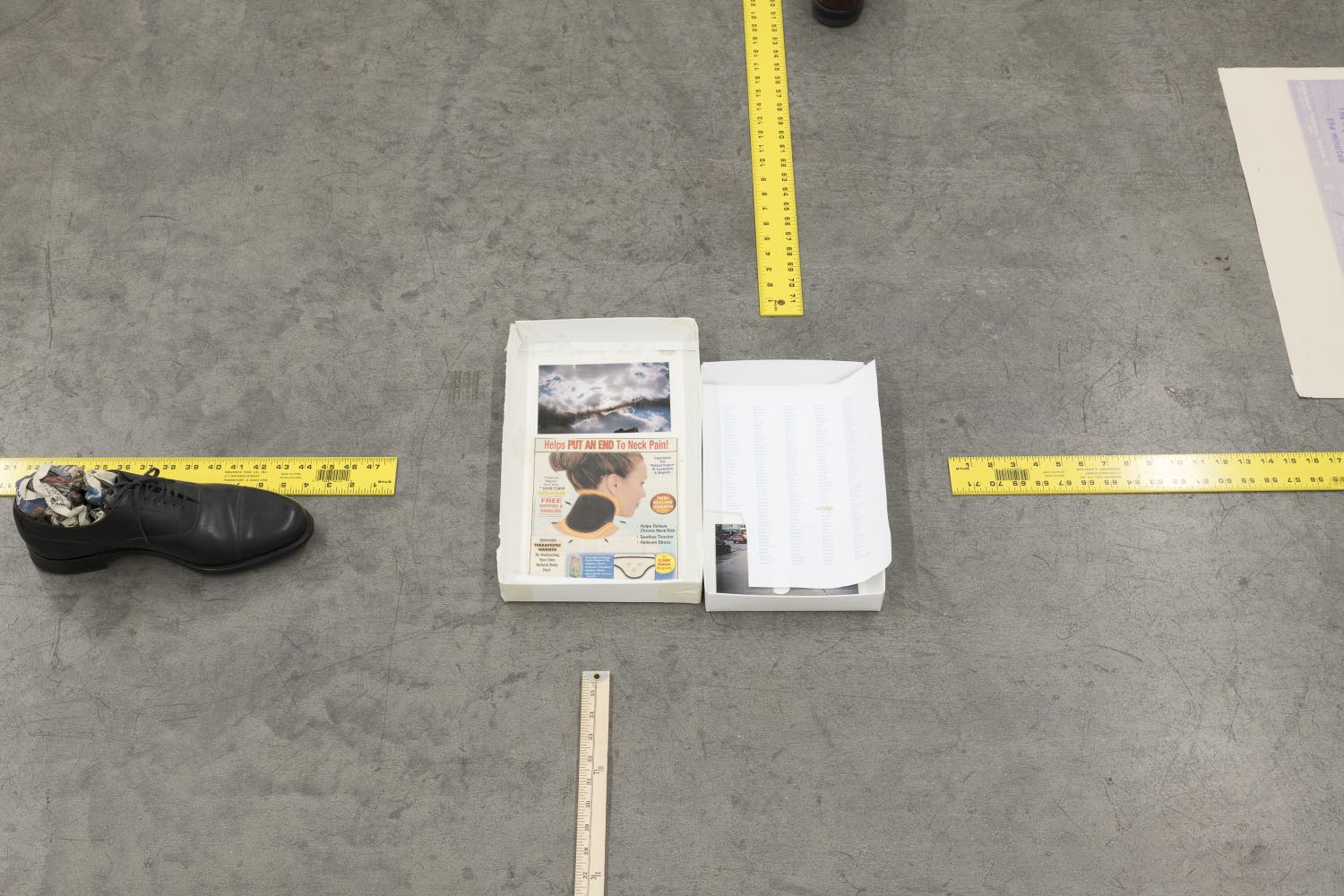

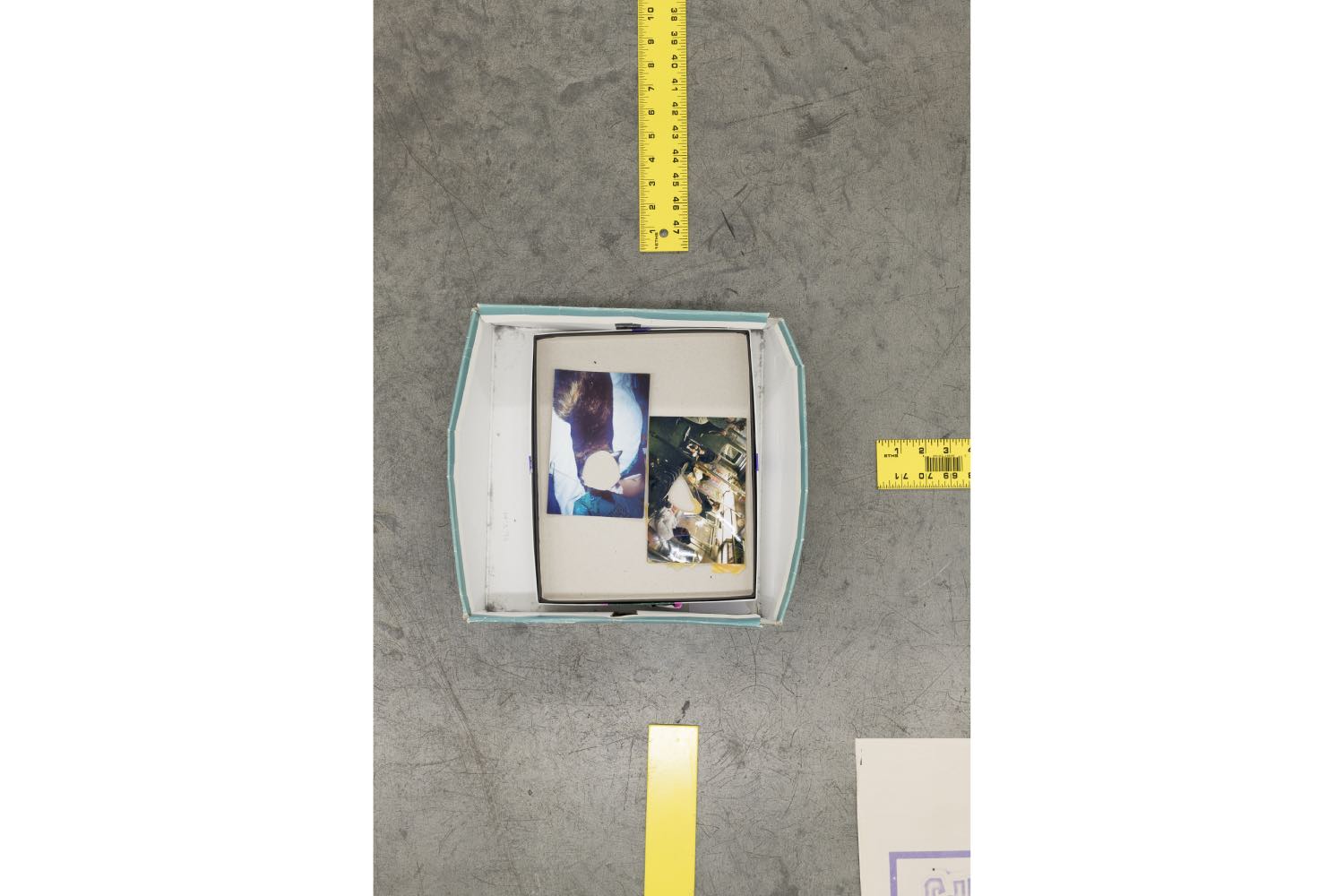

What does a fact express? Is memory accursed by facts, or, in their austerity, do they keep some “truth” intact? McCarthy’s accompanying text for his exhibition “RULER” at Galerie Neu, Berlin (2021), begins with the facts: “My name is Joseph Winston McCarthy. Born July 2, 1986. American.” It then provides a checklist of certifiable and highly subjective criteria for other personal measurements: “Cholesterol” and “Quarterly earning,” sure, but also “Fatigue” and “Personal merit.” Attempts to trace an objective outline of himself become distinctly unclear, its failure compounded by the show itself. Welded rulers line the walls, little cankers created at their unceremonious joining. The floor-based Garden Path Sentence (2021) coordinates space with more rulers, along with assortments of schoolbooks, shoeboxes, and discount store booklets. Figures arrive in obsessive lists of names, adverts of neck pain, sequestered selfies, and strewn baby dolls. In Assembly of Mr. Innocent (2021), a white baby doll is attired in a 1980s suit belonging to the artist’s father, the inner child placed upon a shop table, primed for an autopsy of innocence and intergenerational inheritance. In this aftermath of “boy,” asking what identity is here reveals an interpersonal topography on the lookout for accountability. Stratified by coded masculinities or germinal aspirations, the self is, still, the site of a more existential rub.

Condensations of voice-made material were evident in McCarthy’s exhibition “Apartment Life” (2019) at Svetlana, New York. Svetlana was a storefront gallery located on Manhattan’s Lower East Side near Essex Crossing — a site of extensive real estate development. Here, McCarthy exhibited several rectangular plexiglass structures placed vertically against walls or horizontally on the floor, creating a slovenly set of tenements. Like his portraits, such as Gridlock Person or Untitled (Shelf) (both 2018), which supplant the torso with makeshift cabinetry, the sculptures of “Apartment Life” stockpile the open secrets of transparent containers. These objects include well-worn items from McCarthy’s home, their final setting abandoned in all its natural grime. Light scuds across the glass surfaces, the color of bird shit, as they fail to incubate their spoiling “contents” of some scuzzy mayonnaise jar, dank coffee cup, or otherwise indefinite liquid past its shelf life. Placed upon a cardboard mat, the large glass case of Development (2019) is stickered with doors and windows, and a mirrored medicine cabinet is housed within. Slightly ajar, the cabinet contains only the essentials: back pain ointment, toothbrush, and toothpaste. City Standing Up (2019) is a shallow rectangular glass vessel supported by peanut cans, the whisper of an occupant expressed in a blanket and blown-glass face, suckling a stick of butter. Various containers — coffee cups, a cereal box, water bottles — are swept to its edge as unsheltered remnants scarcely differing from their ghosted resident. Amid this urban vivarium is a remembering of who and what gets lost in a city where attachments to space are wrenched, and sentiments snuffed.

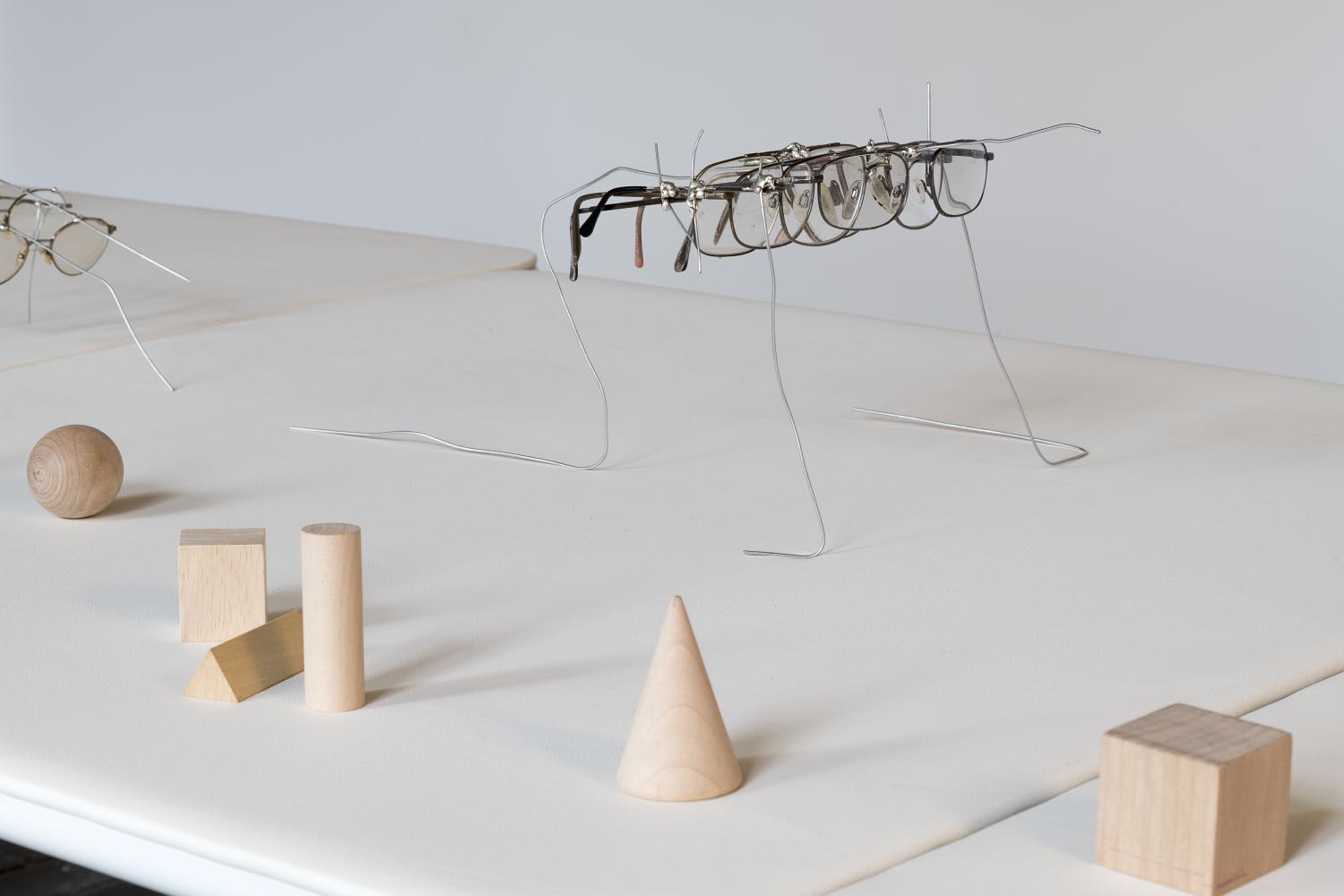

For “Innenportrait” at KW Institute, Berlin (2023), he focused on the physiological act of seeing, straining to take in the sight of others. A possessive thirst pervades this gesture, like placing your hand in another’s pocket: it bears a hint of control and caprice and is slightly criminal. Numerous conjoined or deconstructed prescription eyeglasses, some nametagged and wired atop tripods, are frantic invitations to see through a collective vantage of calibrated visions. A series of “Shoebox Portraits” (2023) rearrange the frames in executions of the drawn line. These sprigs, with their amber nose pads and quality of broken wings, are insectile disfigurations, sylphlike suggestions of their wearer whose eyes are but dreams. A picture of greater clarity is the work’s false hope. There is no first glance, only a catalogue of first freezes that belong to no one, an entropic pull tinged around the rim and paired with welling tension. A tearful downpour all around its shaken peripheral. As with a sequence of photograms that hold up an eyepiece to surroundings — fridge contents, street life — blind fuzz-fields blossom around the lenses’ trembling corona, the glasses offering minor apertures of fluke focus. Limpid moments of entoptic phenomena give these works a fascinating tingle: glassy firmaments, fishbowl dimensions, plasma chills. Wait, this is the picture! Of a mind, at least.

What to make of these longings, that can’t yet hold the shape of their yearning? In another text, McCarthy questions whether one’s past serves or haunts, as though time is either for or against you. Haunting, Mark Fisher writes, “happens when a place is stained by time, or when a particular place becomes the site for an encounter with broken time.”13 But what if that stained place is oneself, and what if one carries that broken time within? Somewhere, at some point, “the city” is a slurry of motions and forces detached from identity. The big-city feeling is exhausting, especially one that never sleeps.

McCarthy’s dispersal of experience suggests a general fading out. But, like his transparencies that become obscuring or his structures warping, perhaps the impending collapse is less a collapse outward than a collapse into, into a greater intensity of presence. It is, then, “terrifyingly present,” as Levinas says. The more present the world becomes the more unreal it feels. Between composition and dissolution, being and nothingness14, McCarthy wrestles with the differences of existence (the fact of existence in general) and the existent (the specified being). Such tensions resonate with Sartre’s infamous passage from Nausea (1938):

“Clear as day: existence had suddenly unveiled itself. It had lost the harmless look of an abstract category: it was the very paste of things; this root was kneaded into existence. Or rather the root, the park gates, the bench, the sparse grass, all that had vanished: the diversity of things, their individuality, were only an appearance, a veneer. This veneer had melted, leaving soft, monstrous masses, all in disorder.”15

Clear as day: the “paste of things” that exerts terrifying clarity. Where “being” smothers “beings,” McCarthy’s weary immersion in the city is barbed and blemished with elegiac suspicion. Plumbing interiority and the dynamics of being ad nauseum, McCarthy’s many infractions on time accrue presence, however disordered. Still, the stain of being cannot find the words and, as befits this irreducibility, likely never will.