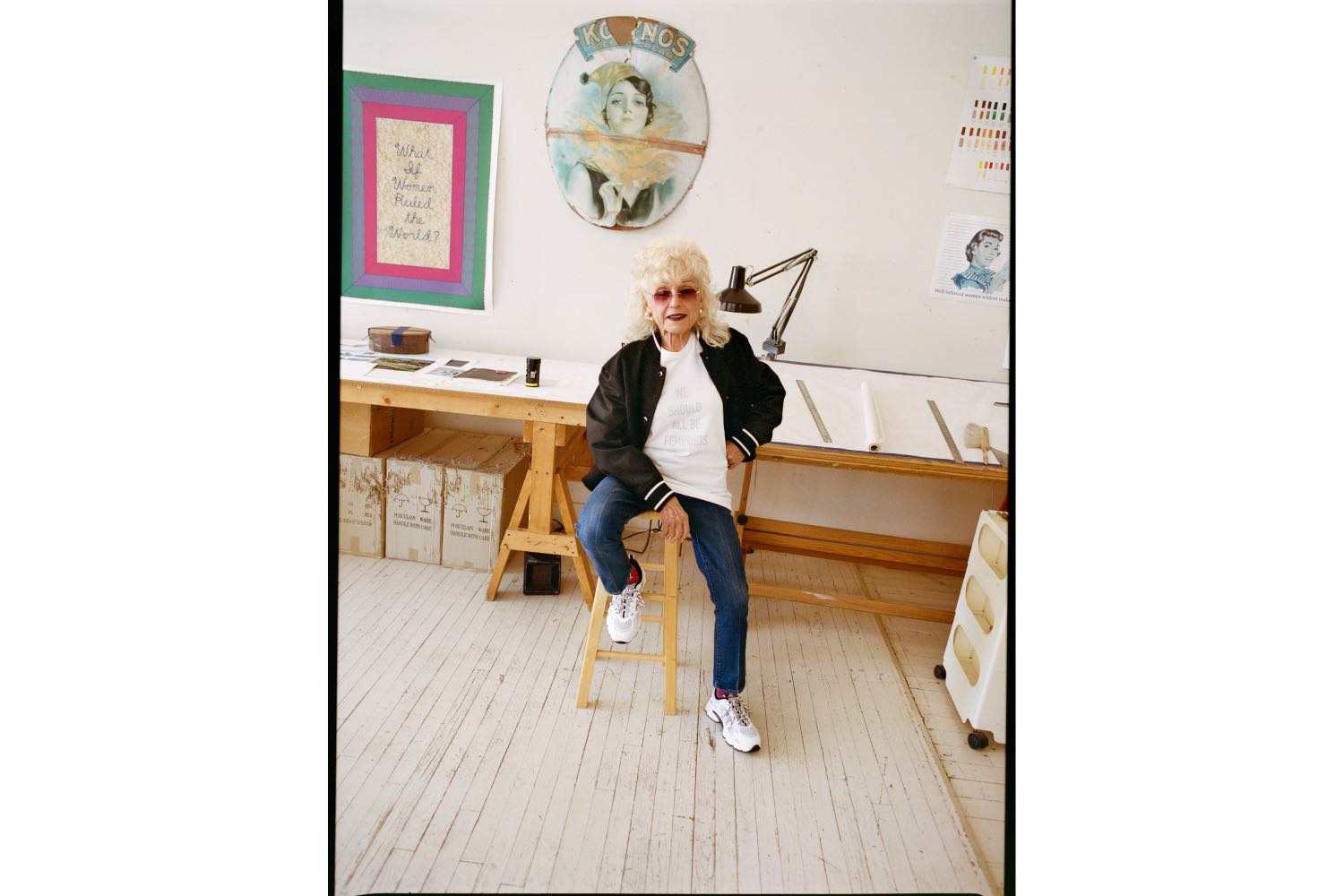

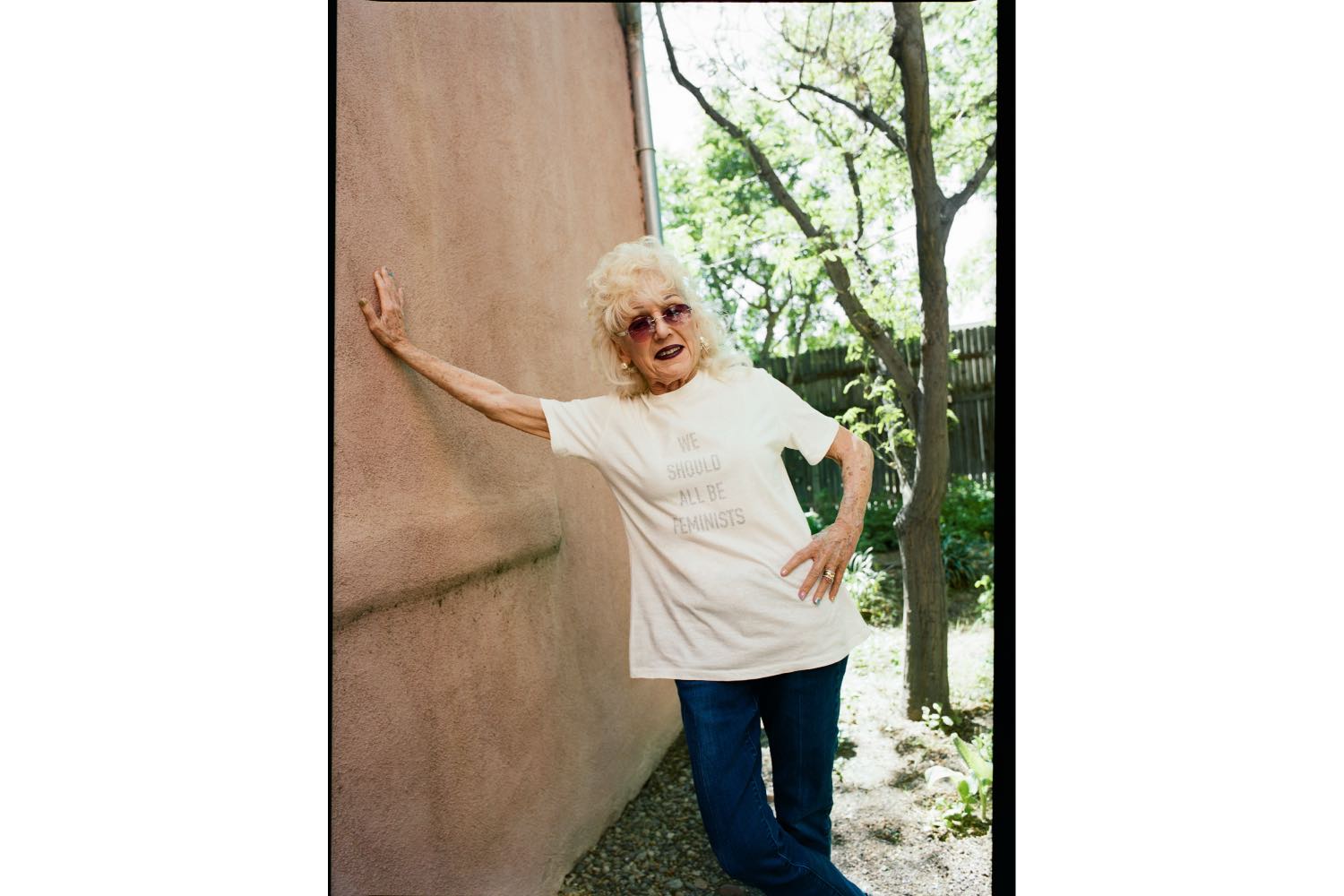

I get a call from Judy Chicago’s studio manager while I’m washing the dishes in my flat. She asks if I can jump on a call with Chicago earlier than our scheduled time, and when I join her at my computer with suds still on my fingers, we launch into a conversation about the power of hands. It seems appropriate that I should first ask about her drawing practice on the occasion of her groundbreaking publication and major retrospective, “Revelations,” at the Serpentine in London. Bringing together archival and never-before-seen drawings and sketches, across both analog and digital presentations, the exhibition offers a radical insight into what has been foundational to Chicago’s work for more than six decades: themes of birth, creation, and the role of women throughout history in a patriarchal art world. A powerful artistic voice in the feminist art movement of the 1970s, Chicago continues to challenge historical perspectives and celebrate the path toward a more just and equitable world. We spoke about collaboration, empowering women, challenging traditional art forms, and inspiring future generations.

Pierce Eldridge: How important has your drawing, sketch, and journaling practice been to you and your visual language as an artist for these six decades?

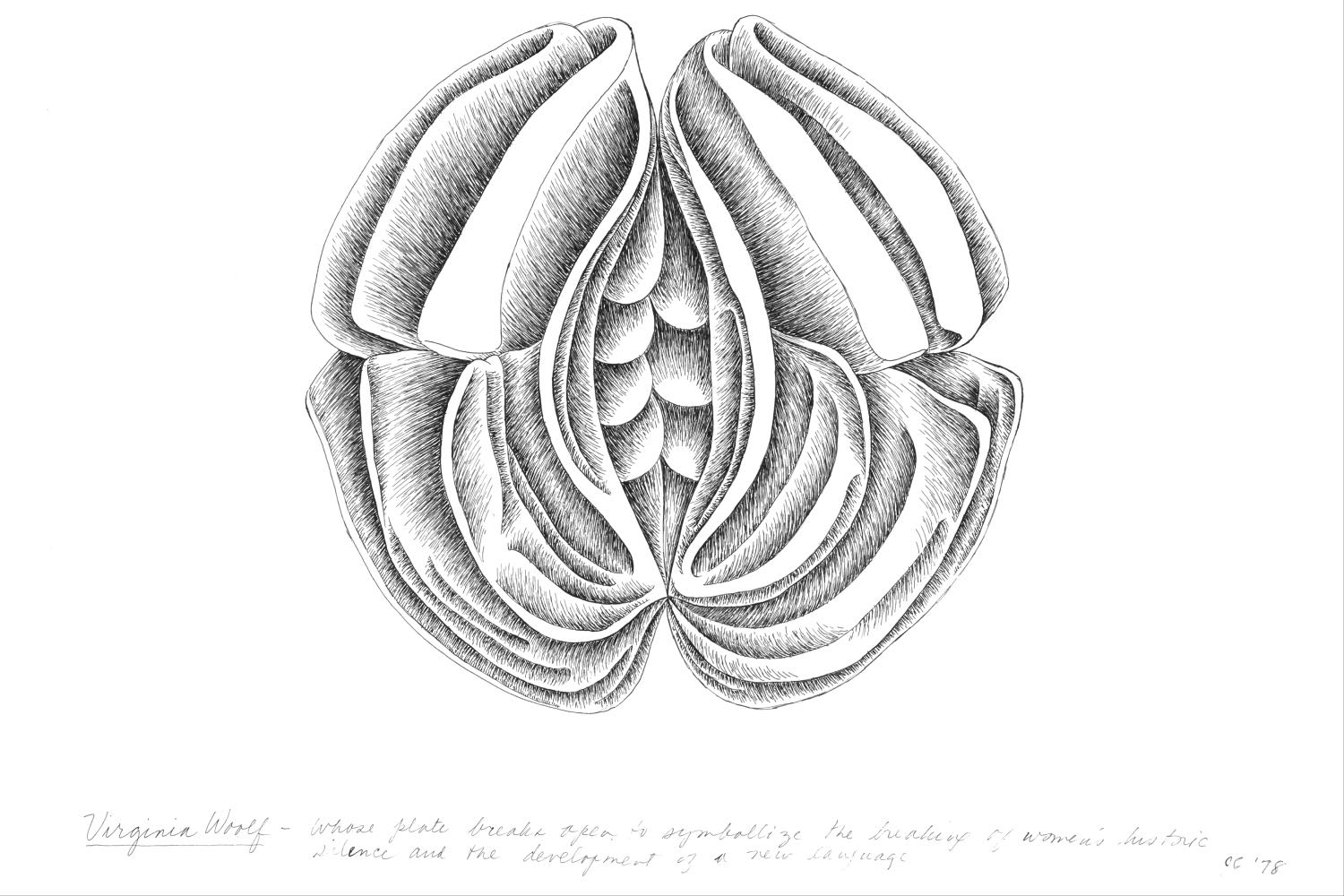

Judy Chicago: I started drawing before I started talking. Drawing is like breathing for me. I always start down the paths of discovery that have characterized my career by drawing with notations. The Serpentine show is a retrospective of artwork as seen through my drawings. It will cross from analog to digital, not only presenting works on paper, which will emphasize the importance of the hand to me in my work, but also through audio tapes, video projections, and three participatory projects that will make evident my collaborative approaches; it’s a very different look at my career that is going to feature a multimedia, immersive environment. People will be able to participate around the world in different ways. Scale has shaped my career because from very early on I thought big. There will be a thirty-two-foot-long drawing that will introduce the show called In the Beginning (1982), which links to the publication, Revelations (June 2024). I came up with Bruce Nauman in Southern California. He and I spent some time together, and one of the things we talked about was drawing. We agreed that you can go a long way as an artist, when you’re young, on the basis of bravado, but, when you mature as an artist, if you can’t draw your growth is inhibited. As your ideas become more complex, it becomes more essential to have drawing skills.

PE Why is that? Why is drawing so essential?

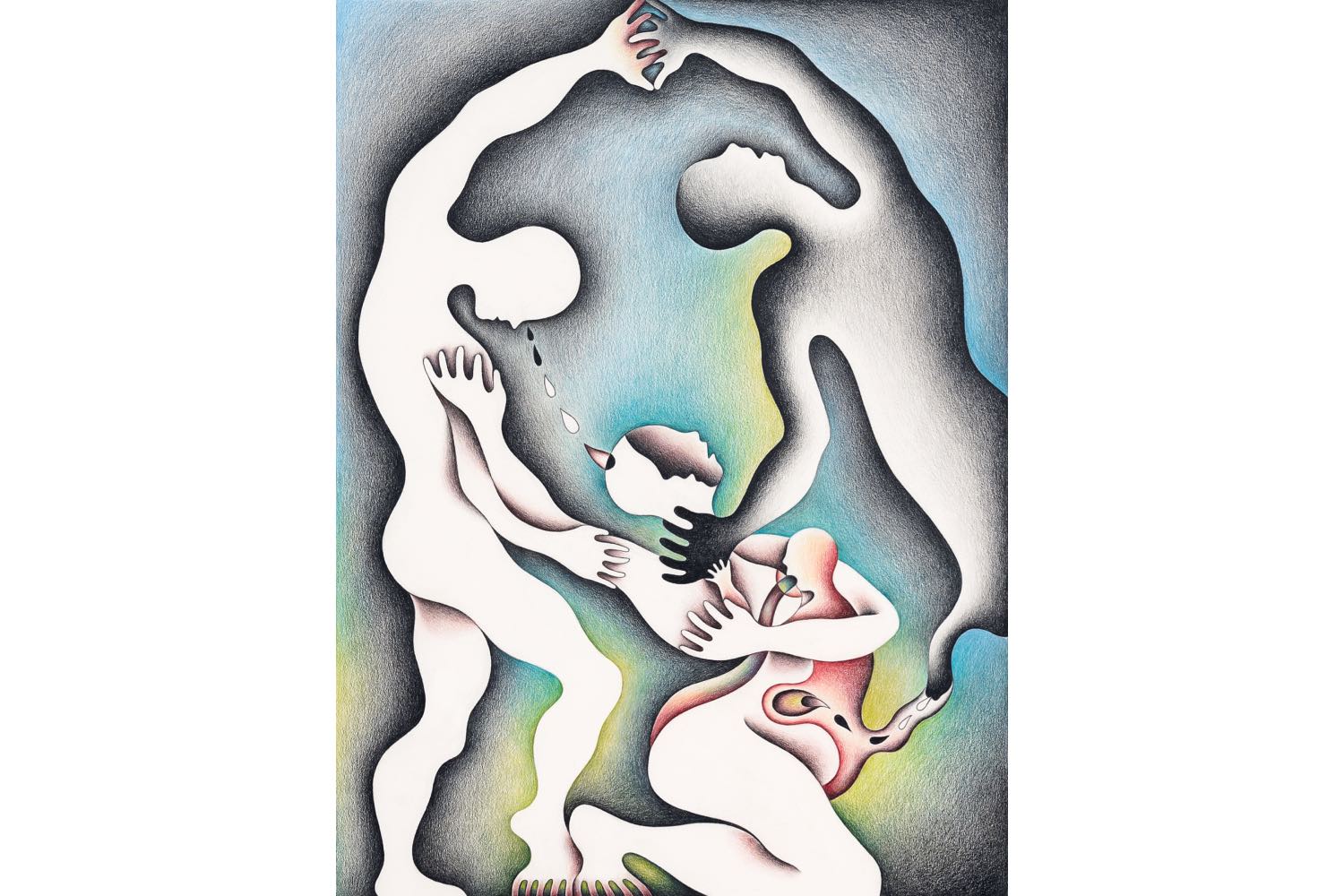

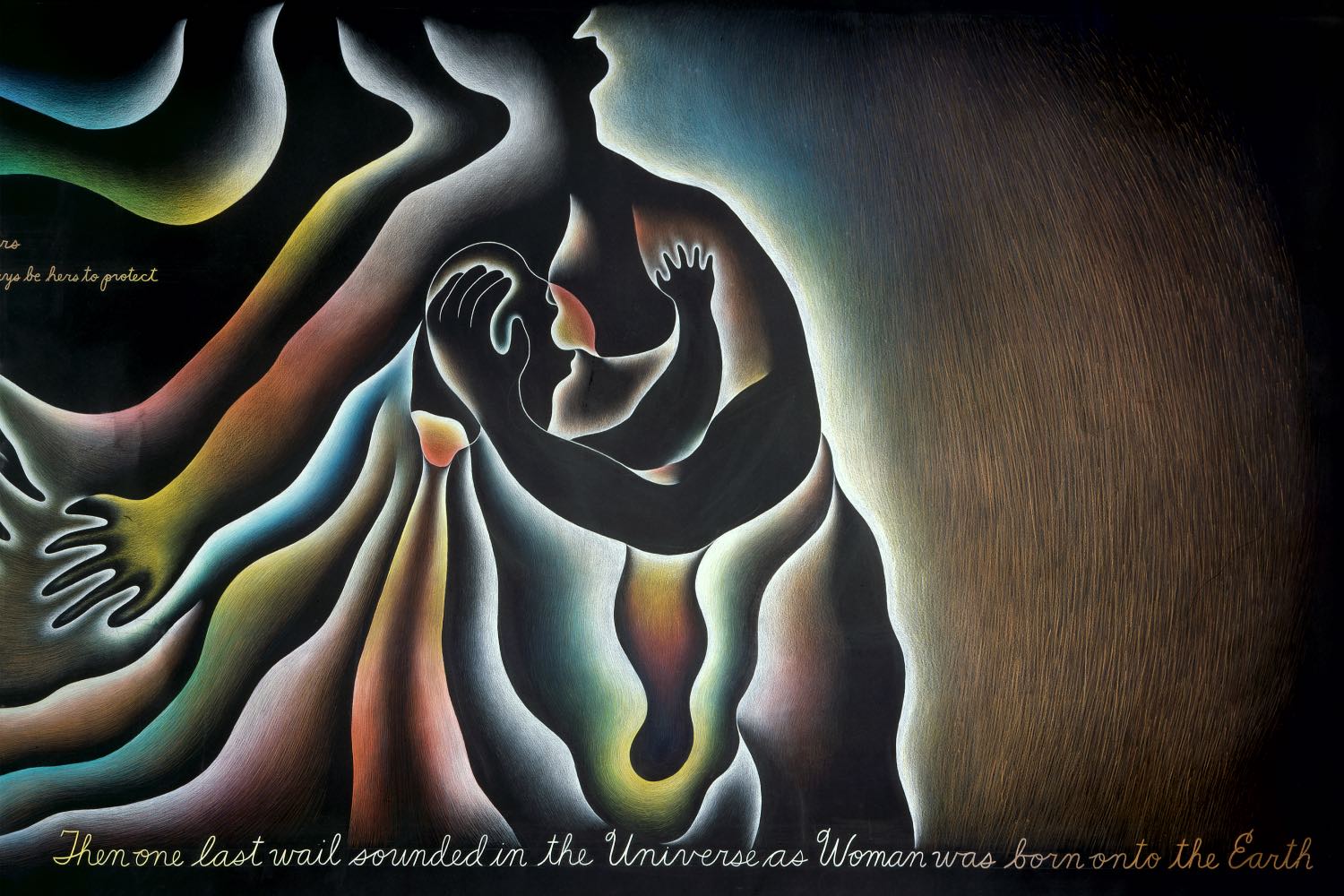

JC Because the hand, the heart, and the brain are connected. I know now the hand has been giving way to digital forms. They’ve done research on children who don’t learn any cursive handwriting skills, and what they’ve discovered is that it has a negative effect on their brain development because they’re now learning entirely online. It’s impeding the development of their brains. If you think about the history of human beings going all the way back to the caves, what do we see there? Cave painting, we see drawings on the walls, on the rocks; the development of the brain and the development of civilization are intimately connected. That’s why I like the fact that my show goes across the spectrum from analog to digital, because viewers will be able to see what can be done with the hand that can’t be done online, along with work that only became possible because of the development of digital technology. There will be some of my earliest drawings in terms of developing the imagery of the Birth Project (1980–85), including the drawings I did when I witnessed my first birth. Now, there is no way on earth that somebody could create that online unless they were in a birthing room, witnessing the birth as I did, and recording it with my hand, my heart, and my brain.

PE The same applies in writing too. Writers who keep diaries or notebooks understand that connecting with a sketchpad offers something you can’t get when you’re engaging with a computer or phone. It makes a lot of sense to me, and feels quite serendipitous, that you should be celebrating that connection in this stage of your artistic practice. I want to return to your point about collaboration. I’m interested to hear how you understand the word as an action, how it relates to your long-standing issue of inequity and inequality, through some of your larger collaborations, for example, your various projects with Dior.

JC I’m still working with Dior. It’s been a great joy of mine. I was first approached by Dior in 2019 to work with Maria Grazia Chiuri, their first female creative director. I remember they flew Donald Woodman and me to Paris in the summer of that year to see our first couture show, which was totally overwhelming because I’m from that generation of feminists that viewed fashion as inherently oppressive to women, a view that has changed as I’ve come to understand that fashion can play an important role in the empowerment of women. It’s male fashion designers who have made it oppressive. Maria Grazia had already started her collaborations with artists, women artists, feminist artists, and there was an installation by an artist in that couture show, but it was basically background to the show. I remember sitting there thinking, “Is there any way art can have a real place in this world?” For me, that was the challenge and still is the challenge in working with Dior. They asked me to make a proposal for a show they were going to hold in the back of the Musée Rodin, which, if you’ve ever been to, you’ll know is a paean to masculinity. They were going to erect some kind of temporary structure. So I asked if I could design that.

PE Tell me more about this.

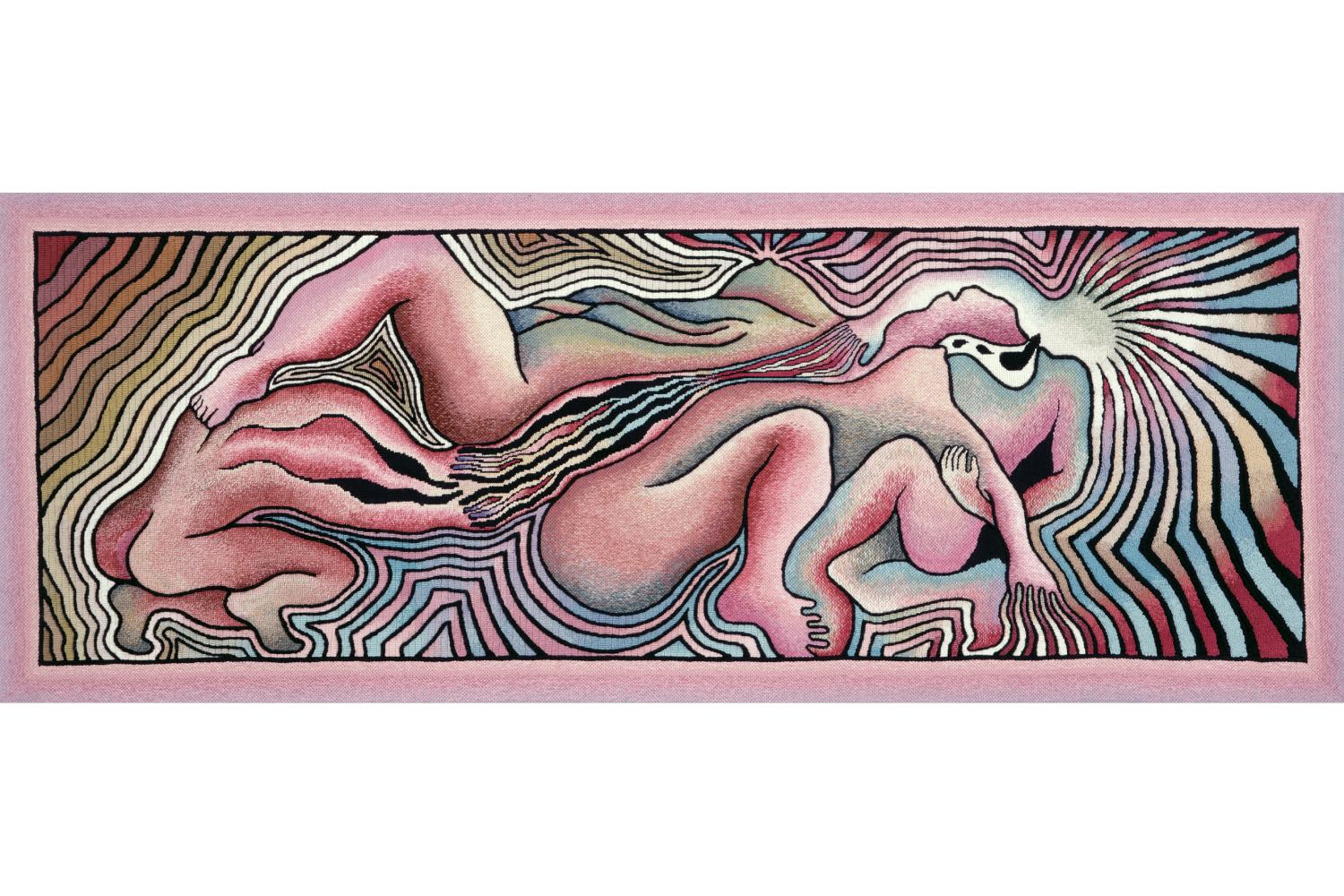

JC I had an unrealized project from the ’70s, an inflated goddess figure. It was sixty feet long in my imagination, which at the time I thought was pretty big. I made a proposal for a huge goddess figure in whose body the show would be held, and the interior was gold. The figure ended up being two hundred and twenty feet long. It was the first time in my life that something exceeded my not-so-small ambitions. We had a lot of interaction, the whole Dior team came to Belen, the small New Mexico town I live in, including Maria Grazia. I originally proposed a series of banners that would have questions on them. We had only five months to do this enormous project. Maria Grazia was inspired by my banners from The Dinner Party (1974–79), and that meant redesigning them to include imagery, which was very time-consuming as it involved a lot of hand drawing. She brought in the Chanakya School of Craft (helmed by artistic director Karishma Swali), which is a school in Mumbai that trains women in needlework. Training these women is a way of helping them develop independence. In India, professional needlework is usually done by men. I designed this series of ten large banners, both in French and in English, that hung inside of the goddess figure. There was a six-meter-high banner that said, “What If Women Ruled the World?” The questions I raised were difficult questions: “Would Buildings Resemble Wombs? Would God Be Female? Would Both Women and Men Be Gentle?” These questions were so foreign to young women in Mumbai that, in addition to needlework training, the school actually had to provide them with empowerment training to help them relate to the meaning of what they were fabricating. I bring this up because we were creating an impact through art which has been one of my lifelong goals, and we were doing it through a transnational collaboration. I was in New Mexico, Maria Grazia was in Paris, and the women were in India, which was very thrilling to me. And then these banners became the basis for a Web3 project with Nadya Tolokonnikova from Pussy Riot. Sponsored by DMINTI, it is one of the three participatory projects at the Serpentine and will allow people around the world to formulate their own answers to the ten questions I raised.

PE Let’s talk about Revelations. I want to know how it feels for this to finally be published. But I also want to hear how you came to the idea of subverting the patriarchal Genesis and how you’ve embedded new mythologies through a female perspective?

JC I’m very happy to be talking about this because the advanced copies have been sent out and you’re probably one of the first people to get one. I’ve been very eager to see what kind of response there is to it. It’s important to understand the relationship between the New Museum show, the Serpentine Show, and the publication of Revelations, as everybody who knows anything about my career knows I’ve had a really long and hard struggle up against a solid wall of resistance and a complete lack of comprehension of who I am and what I believe in as an artist. For example, when we were talking about drawing, there was a period of time when art writers actually said I couldn’t draw.

PE I’m sure this was misogynistic and derogatory…

JC Exactly! It’s also another way to minimize the importance of my work to the worldwide audience that I’ve built. I have always had a passion for equity and justice and tried to express that through my work, but I was attacked for being “naive and simplistic.” I’m like, “Right, I spent eight years with my husband, photographer Donald Woodman, in the darkness of the Holocaust [Project], and I’ve come out of it stupid about the world?” No. I came out of it with a more profound understanding of the world, and for me, a deeper understanding of women’s oppression in the world because I realized it was part of a global structure of injustice and oppression that is intimately tied with patriarchy. The New Museum show included a section called “The City of Ladies,” which is named after The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) by Christine de Pizan. It contextualized my work in five centuries of women’s cultural production and presented an alternative, female-centered art-historical paradigm. That was a very important step in changing what’s happening in terms of the perceptions of my work that seem to be happening now, because it demonstrated that for decades I have been working out of this alternative cultural and artistic paradigm; one that challenges patriarchal art history, which for way too long has been considered universal and depends on the erasure of the histories of multiple peoples. What the Serpentine show and the publication of Revelations will do is to illuminate my underlying vision. That’s why it was so overwhelming to me when Hans Ulrich Obrist (Serpentine’s artistic director) saw the manuscript and said it prefigures my entire career. It made me break into tears. How do I feel about my vision finally being clarified through Revelations? Thrilled and terrified…

PE I’m sure you’re oscillating between those feelings, but surely there is a sense of pride in finally being able to see it published?

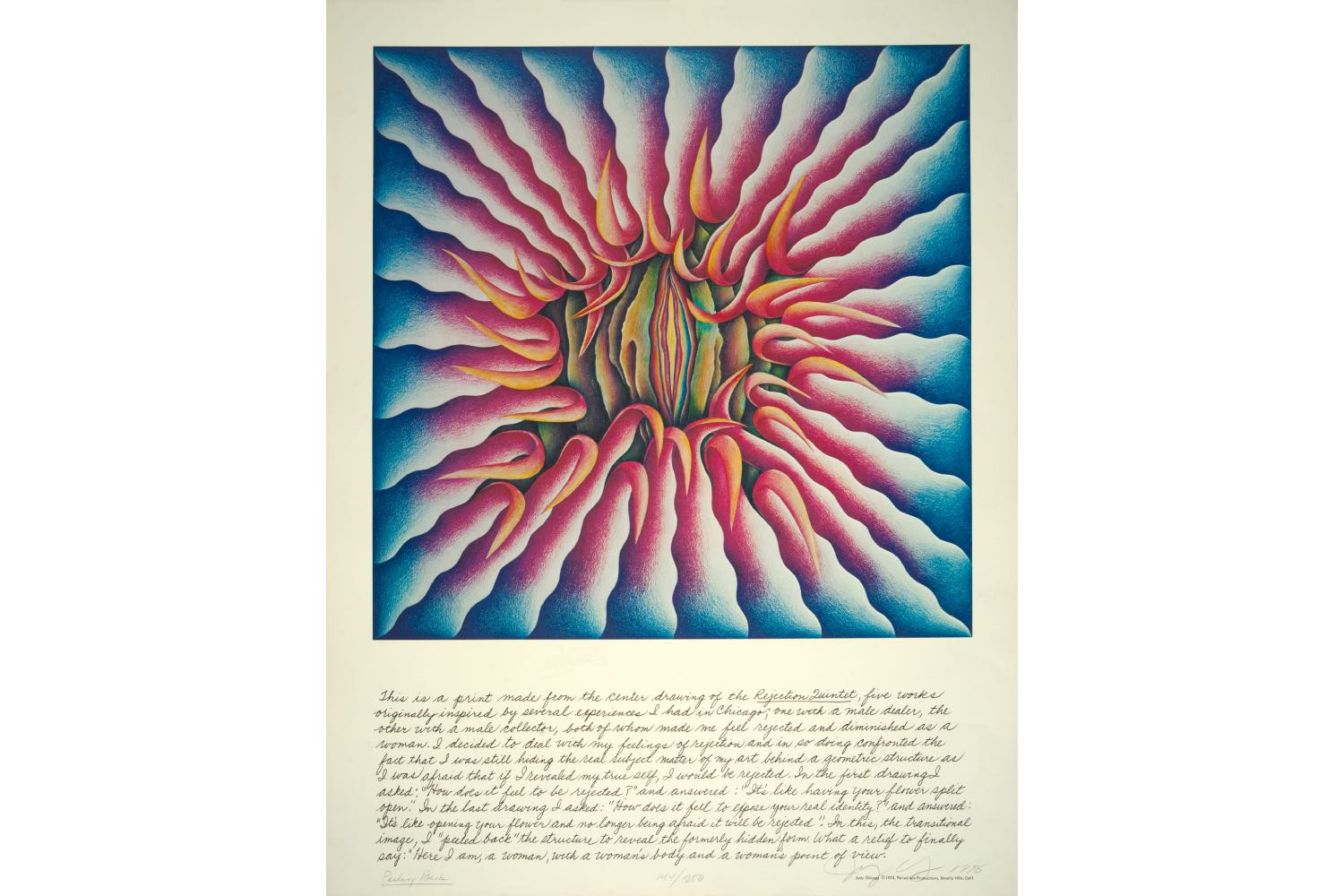

JC Of course. But was a very fast turnaround for the book. I sequestered myself for five months and achieved two things. The first being an update of the manuscript because my thinking has evolved since I wrote it. The second was to update some of the original illustrations and to add a lot of new illustrations, but I could only do that by completely isolating myself and needing uninterrupted focus for five months because I was delving back into material that was so close to my heart. That’s why I’m really eager to hear about how you responded to it, because it’s totally unknown to me yet how people are going to react, whether they’re going to find it relevant now or not. So now it’s your turn.

PE To give you some gratification in how I’m reading it, I am a trans person, transitioning from male to female, and it’s actually quite interesting to see the flip of the binary in Revelations, particularly in relation to your body of work as it addresses power, birth, masculinity, and justice. A lot of my own experience and work addresses this too. There’s a beautiful passage I wanted to read back to you: “And like a miracle, again and again, Woman’s body swelled and strained and labored to create life. And Woman’s companion, Man, stood before her in awe. He watched her body expand and open and give birth. He saw her breasts abound with sweet milk. And he entered her body in trembling and drank from her breasts in thanks, and in the fullness of her flesh he understood the holiness of life.” I don’t subscribe to any form of religion, I was raised agnostic, but there is something inherently very trans about that passage to me. It’s poetic, it substantiates these ideas I have of myself between the gender binary to watch the man of me be a companion to the woman that is, and has always been, the holiness inside of me. I feel like I’ve arrived, whilst reading, to a scripture that is essential now more than ever.

JC I feel very gratified by your response, thank you.

PE There’s a beautiful sentiment you express in your introductory essay, that the issues which have guided your practice still need addressing today; because we might be doomed, on an ecologically dying planet, still facing great adversity between genders, species, ecology. How do you feel the passage of time between the “then” and “now”? Are you able to see the shift in your thinking from when you began writing? There must be some interesting complications that you feel within the values you hold and how they have evolved over time.

JC Those are big questions.

PE All of which emerge from your work. Everything feels like it’s coming to a pinnacle, but didn’t it feel this way to you all along?

JC I have to say, when I was working on the manuscript and rereading Revelations, I was kind of taken aback by how, fifty years ago, I predicted what is happening now in terms of planetary collapse, the destruction of other species, and the disdain for the planet. That’s all in Revelations. But the hope for change that informs the book is the vision that has sustained me. However, it was, and still is, so far outside of the market-driven art world it resulted in my being marginalized, disdained, and rejected. I had to separate myself in order to pursue my own vision because I’m so out of line with the mainstream, as you pointed out. But there are a lot of people who are out of line with the mainstream, and to embrace them, to give space for them and their voices, has been my goal as an artist for my whole career. One of the things in terms of how my evolution, how my development has changed my thinking, is that in the ’70s I saw everything through the lens of a kind of binary gendered idea. That has definitely changed in Revelations as a result of the way that thinking about gender has evolved in the ensuing decades.

Additionally, when I was young, I thought that big ideas required big scale outcomes, hence the thirty-two-foot In the Beginning (1982) drawing. But I now understand that sometimes big ideas are best expressed in a small, intimate context that invites people to look at them closely and think about them deeply. Even though I spent all that time on the subject of the Holocaust, the “Extinction” series was the most grief-inducing work I have ever done. For two years I was immersed in trying to figure out how to convey not only what we’re doing to other creatures, but the scale at which we’re doing it, in a way that would allow people, compel people, to look at it. That was a huge challenge. It called on all my skills as an artist. Again, I had to be almost completely isolated inside our space, with my husband, our cats, and our small staff in order to do it because it required such intense focus. I was trying to express the horror and grief I felt at our treatment of other creatures through my hand, my heart, and my art; the work is all very intimate. It’s like you were talking about; we have to face this as a human species or we will not survive. If my art and if Revelations can help us do that, can help make a difference, and also a contribution, to the overcoming of the erasure of women’s cultural production — including my own — working toward justice and equity for all creatures on the planet, human and nonhuman, then I have achieved my goals as an artist.

PE That’s a huge triumph to say as an artist. Which begs the question, having reached this moment: What comes next?

JC I’m going to be eighty-five in July and I’m not going to retire. However, I am going to cut back on public life because it takes a lot of my energy. I have a project that I had to put aside, that I started some time ago, because of all that has been happening during the last year; three major museum exhibitions, the publication of a book I never thought I’d live to see published, a new fireworks piece at my upcoming show at the LUMA Foundation, plus another Dior project. It’s a LOT for an old lady. The wall of resistance seems to be crumbling and has turned into a tsunami that I’m trying very hard to not be drowned by.

PE You’re returning, or have just gained access, to being an oceanic species, Judy.

JC [laughs] How will I draw, how will I breathe?

PE You’ll develop new gills and a flipper. [laughs]

JC [laughs] Yes! This has been a really fabulous conversation.

PE For me too, thank you. One final and ambitious question for you: How do we come together to dismantle the patriarchal paradigm for the benefit of humans and nonhuman entities?

JC I’ve given it my best shot. It’s going to take a hell of a lot more than just me. It’ll take people across the gender spectrum coming together and working together. I won’t live to see that, but if my work contributes even a little bit to that, my life will have been worthwhile.