Urs Fischer’s retrospective at Palazzo Grassi, Venice, comprises works made between the early ’90s and the present day, and starts in the building’s hall with the installation Madame Fisscher. Lending its name to the entire exhibition — curated by the artist in collaboration with curator Caroline Bourgeois — this work alludes to Madame Tussaud, founder of the wax museum, but also evokes Duchamp’s Rrose Sélavy (1921).

Fischer’s lively and ironic works continually surprise the visitor. His oeuvre reflects a sharp sense of humor and paradox regarding the state of art and sculpture, the relationship between the object and its image, the human body, nature and its representation. Fischer meditates on the perpetual change and movement of things, drawing inspiration from the history of art, but also from poetry, music and neo-noir films such as Pupi Avati’s The House of the Laughing Windows (1976) and Jack Nicholson’s Drive, He Said, (1971); both movies are on view in two small cinematic rooms set up for the exhibition.

The artist uses this occasion to create a multi-faceted ensemble of works — a kind of Gesamtkunstwerk that metabolizes and is influenced by Franz West, Martin Kippenberger, Paul McCarthy, Thomas Hirschhorn, as well as Salvador Dalì and Jean Tinguley. Concentrating on various aspects of contemporary sculpture, Fischer uses them as a departure point to link pop objects, suspended casts of fragmented body parts, surreal compositions made with vegetables, cakes and other kinds of food, all destined to deteriorate during the course of the exhibition.

The show presents many unexpected changes and swift transitions that reflect the artist’s complex inner ludic world. As Fischer states, “In sculpture, one can add or take away.” There are fragments of cast figures, wax objects, polystyrene forms, aluminum sculptures, found objects, a washing machine with a goose and a cat covered with an even white patina (Cappillon, 2000), notes, sketches and small-scale models on the walls, torn sheets of paper treated as rubbish, surrealistic and hyper-realistic silk screens depicting beautiful female faces crossed by gigantic bolts, oversize nails that lean on the wall to create shadows and suggest the relationship between object and image.

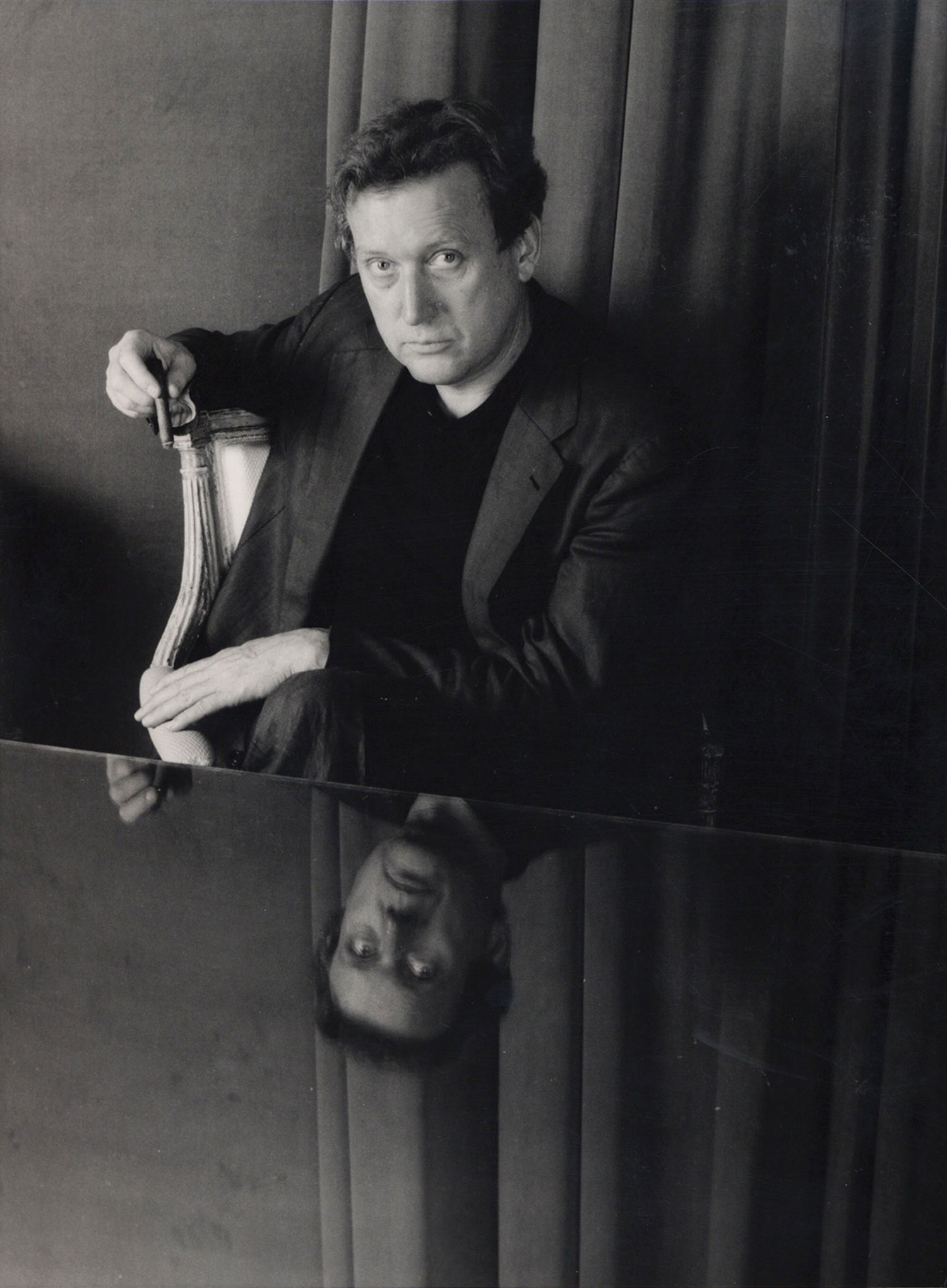

In Necrophonia, an installation created in collaboration with Georg Herold, a real model places herself next to the objects and the aluminum sculptures. The candle sculptures, a self-portrait and a portrait of the artist’s friend Rudolf Stingel, melt down in a purposeful way, following a well-calibrated process. We almost step on a shriveled Camel packet hanging from an undetectable wire dragged by a mechanical arm in an otherwise empty room of the palace. In this way Fischer has carefully calculated the visitor’s path. In some ways his art can be compared to slam poetry, in the sense of having a performative aspect that demands the viewer’s attention.Part of the exhibition is dedicated to Fischer’s special project made with the students of the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, which features the creation of sculptures located around Venice, meant to disintegrate over time.