The frightening theme of global warming is often addressed in catastrophic terms expressed in visions of utter annihilation. At times this possibility is made surprisingly plausible, as in an excerpt from Bill McKibben’s new book Falter published recently in “Rolling Stone”.1 McKibben argues that we should not only think that the human population could be drastically reduced by global warming, but that outright extinction is on the table. Among the chief factors he mentions are that the upper levels of atmospheric CO2in play for the year 2100 could lower human cognitive ability by a harrowing 21%, and that the nutritional value of many staple crops is already decreasing rapidly. This ups the ante considerably from a 2007 “Rolling Stone” piece by Jeff Goodell about climate scientist James Lovelock, which projected a much smaller disaster: “By 2100, Lovelock believes, the Earth’s population will be culled from today’s 6.6 billion to as few as 500 million, with most of the survivors living in the far latitudes – Canada, Iceland, Scandinavia, the Arctic Basin.”2

In one respect, the relative likelihood of these two scenarios (and others) is simply an empirical question for climate scientists to sort out. But in another sense, McKibben’s apocalyptic scenario runs the risk of feeding a deep-rooted philosophical prejudice that we ought to resist on principle. Namely, the modern period tends to create a taxonomy in which there are only two elements under discussion: (1) human thought, and (2) everything else, sometimes called “the world” for short. Thought is treated as the realm of immanence and immediate accessibility, while the world is considered to be something so unknowably “other” that it tends to be theorized in drastic and global terms. One such case is the “sublime,” which Immanuel Kant defines as the absolutely large (the mathematical sublime) or the absolutely powerful (the dynamical sublime).3Jean-François Lyotard is perhaps the leading recent theorist of the sublime viewed as otherness, a major topic for Emmanuel Levinas and later Jacques Derrida as well.4Another influential attempt to treat the outside of thought in catastrophic terms is that of the Real as described by Jacques Lacan, modelled as an immanent breakdown of the symbolic order.5An earlier and even more famous theory of access to the absolute other of thought can be found in Martin Heidegger’s concept of Angst, as a fundamental mood that brings being as a whole into focus in a way that normal cognition cannot.6 A more recent analogue would be Alain Badiou’s conception of every finite situation as a counted or “consistent” multiple, one that is shadowed by a void that erupts in the form of various shocking and unforeseeable truth-events constituted retroactively by the fidelity of a subject.7 Whatever their differences, what all such theories share is both their implicit treatment of the outside as an unformatted singularity, and their tendency to reduce the role of this outside to a sweeping disruptor of immanent human cognition. Here I wish to challenge this conception of the outside. First, although often threatening –as the ongoing climate scare emphasizes – the threat of the outside should be conceived in finite terms, even if the threat is a truly colossal one. And second, the real should not be treated merely as something other to humans, an artifact of modern philosophical bias that haunts even the most recent advanced philosophies. I will close by considering briefly some of the implications for artistic and curatorial practice.

Large Finitudes

My standpoint here, as always, is that of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO). It was Steven Shaviro who first criticized a purported link between OOO and the Kantian sublime:

Harman… appeals to notions of the sublime: although he never uses this word, he refers instead to what he calls allure. This is the attraction of something that has retreated into its own depths… Allure is properly a sublime experience, because it stretches the observer to the point where it reaches the limits of its power, or where its apprehensions break down. To be allured is to be beckoned into a realm that cannot ever be reached.8

One problem with this passage is that in Kant’s aesthetics it is not just the sublime, but even the beautiful that “cannot ever be reached.” After all, the Kantian beautiful cannot be grasped in terms of rules or criteria, but is to be judged by taste alone. Whereas earlier thinkers of beauty had surmised that anything beautiful ought to be symmetrical, or not too large, or should inspire us to rise from erotically exciting bodies to a higher realm of forms, Kantian taste leaves no room for such principles. This was explained lucidly by Clement Greenberg early in Homemade Esthetics, in his contrast between T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land and a less distinguished piece of verse by Sir William Watson.9 If rules for the beautiful could be given, Greenberg noted, then it should be possible to produce excellent art or criticism simply by following those rules, though it is clear that this never happens.

It might appear, then, that OOO’s concept of allure is merely indifferent to Kant’s distinction between the beautiful and the sublime, since both are beyond the reach of direct cognitive access. But in fact, the situation is even worse for Shaviro’s argument, since he gets it backwards. For what he fails to mention is that the Kantian sublime refers to the “absolutely” large or powerful. If something overwhelms the human scale, it would matter little for Kant whether it is the universe as a whole or the comparatively tiny Atlantic Ocean; as long as it overpowers us, we need not consider whether it is a mere tsunami crushing a nearby city, or a supernova that annihilates the solar system as a whole. While Kant was surely aware of this, he treats the sublime solely by contrast with the human framework, and thereby effaces all difference in magnitude between various instances of the sublime.

It was Timothy Morton, with his important concept of “hyperobjects,” who first placed OOO and the sublime at a permanent distance from each other. As Morton puts it: “Infinity is far easier to cope with. Infinity brings to mind our cognitive powers. . . But hyperobjects are not forever. What they offer instead is very large finitude. I can think infinity. But I can’t count up to one hundred thousand.”10 While it is true that a plastic cup and radioactive waste both decay at rates far exceeding the average human lifespan, each can be measured – or at least estimated – in finite terms, and the difference between them need not be ecologically or even anthropologically irrelevant.

The Real in its Own Right

The taxonomy arranged by modern philosophy between thought on one side and “the world” on the other has led to a tenacious division of intellectual labor. Namely, the humanities and social sciences deal with the relations between humans and various parts of the inanimate world, while object-object relations are left as the special preserve of natural science. Although largely taken for granted today, this taxonomy is invalid. Kant’s distinction between noumena and phenomena need not be taken as a special fact about tragic human finitude, but must be extended – as OOO does – to cover any relation between any two things at all. As Morton argues in his controversial Realist Magic, just as humans anthropomorphize the world by perceiving, sand “sandpomorphizes” the sea that strikes against the beach.11 The Real does not just gum up the symbolic order, as Lacan has it; among other factors, we should note that parts of the world interact with each other even when no humans are present. Such interactions cannot be left to the natural sciences alone, since they have a particular way of treating them that does not exhaust the topic: namely, the sciences treat nature as physical beings whose movements and forces can be expressed in cleanly mathematical terms. As Morton argues, there is also a metaphorical aspect to physical causation no less than we find in literary texts, and a good ontology must find a way to account for how an orange or baseball translate other inanimate objects into caricatures, just as Kant said of the human mind.

Implications for the Arts

With space running short, we turn now to the arts. Just like ecology, the arts are often tempted to view the outside of their sphere as something unformatted and singular, something that happens both in traditional formalist criticism and in the anti-formalist currents that have largely prevailed since the 1960s. Clement Greenberg’s flat canvas background is no more differentiated than Heidegger’s Being or the inconsistent multiple of Badiou.12 Nor are matters improved when he complicates this background by invoking the collage techniques of Braque and Picasso, which merely shifts the terms from a single background plane to multiple competing planes brought about by the pasting of ambiguous entities such as trompe l’oeil lettering or imitation wood-grain paper onto a previously unalloyed canvas plane.13 In short, Greenberg falls prey to the same sort of holis mfound in too many ecological theories. Yet the same thing happens in numerous genres of post-Greenbergian, post-formalist art. One example is the turn to “the abject” in much contemporary art, which resonates not only with Julia Kristeva’s original use of the term and George Bataille’s appeal to supposedly formless “spider or spit,” but also with the Lacanian Real and its inability to do anything other than traumatize human experience.14

The other implication of unsublime ecology is the need to account for object-object relations apart from human access to them. This is admittedly complicated by the fact that art necessarily has reference to a human beholder, and cannot give in to what Michael Fried calls the “supreme fiction” that no one is looking at it.15 Yet in a sense the same is true of science, which treats inanimate relations in a mathematical language that fails to exhaust objects, merely formalizing their spatio-temporal properties in a way that is cognitively accessible even as much else in these objects is left out.

Accordingly, I would say that there are two ecological implications for the contemporary arts. The first is that ecologism does not equal holism. Although we may think of Lovelock’s Gaia as a holistic interpretation of the earth as a unified organism, this is misleading.16 What Gaia really means is not that everything is linked with everything else, but simply that earth life generates climate through its own activities rather than relying on it as an inanimate background given. In his public appearances, Lovelock frequently notes not that “everything affects everything,” but that a small number of looming factors play an outsized role in threatening the current biosphere: to be specific, the death of the rain forests, the death of algae, and the melting of the permafrost in Canada and Siberia. The contemporary arts (like contemporary philosophy) must cease to interpret that which is outside direct human experience as a single inarticulate lump, but find some way to distinguish between important and unimportant aspects in the depths of otherness.

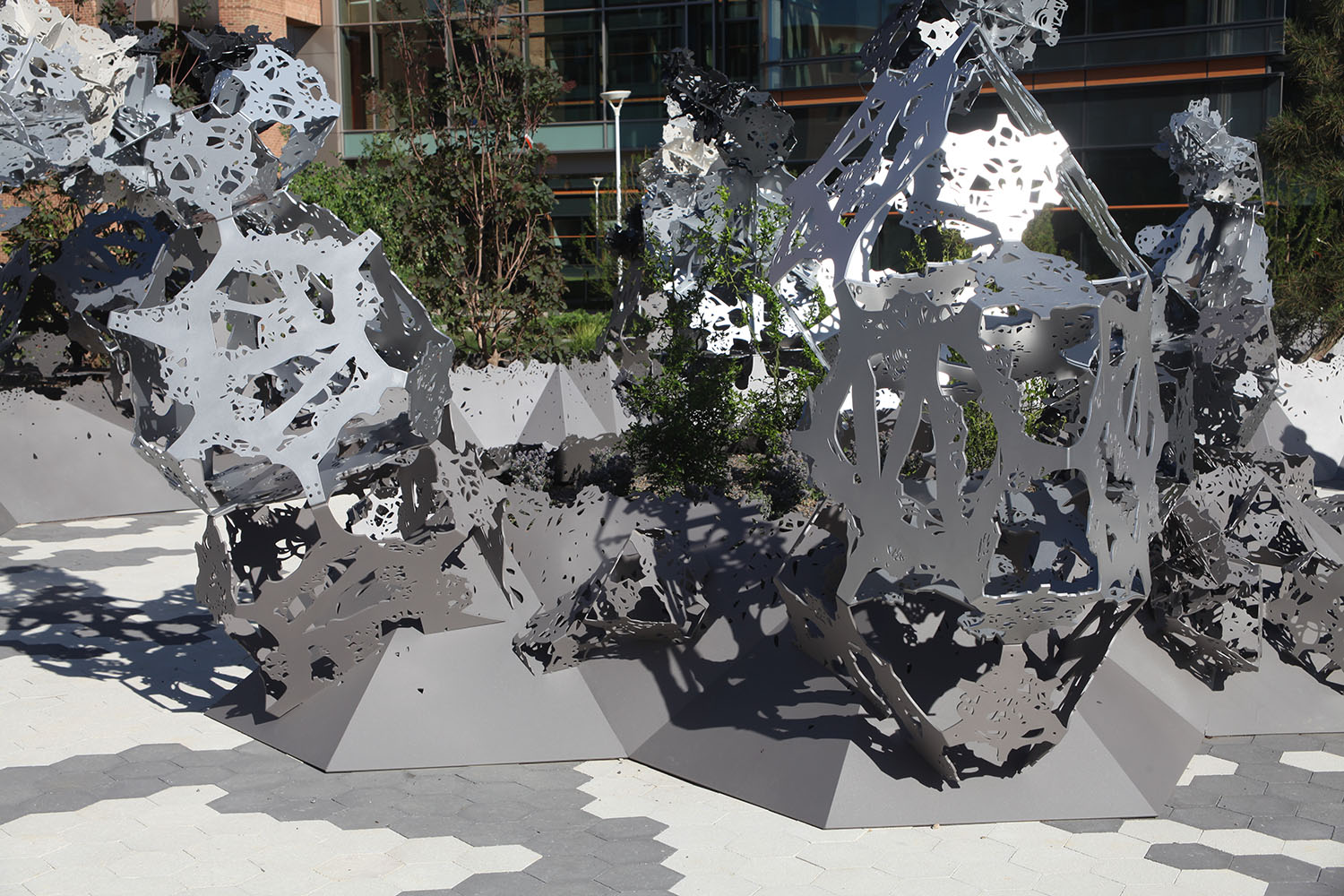

The second implication is that non-human objects are largely indifferent to humans, but interact with each other far more than with us. If Morton is right that this involves translations of a largely metaphorical character – and I think he is – then this places a new burden on the arts unknown in their previous history. For even if it were merely a “supreme fiction” that humans might address object-object interactions without affecting them in some important way, the attempt must be made if art is to learn the lessons of unsublime ecology. We can happily leave the mathematizable spatio-temporal properties of nature to the sciences where they belong. But the time is ripe for art that explores unforeseen interactions between the different parts of the external world, in ways that bring fascinating new properties to light. As an example, consider Matthew Ritchie’s garden of invasive plants in competition with each other at the building of the United States Food and Drug Administration. Although pitched by his gallery – and perhaps even Ritchie himself – as “invit[ing] interaction with the public,” more interesting is what happens when these plants duel to the death with each other, without interference from humanitarian gardeners.17 What better way to approach an environment freed from the platitudes of holism, beneficence, and wise human stewardship?