It goes without saying that sound as an artistic medium has a rich and varied history; think only of the Italian futurists or Fluxus. But a solidified, one might even say institutionalized, category of sound is arguably a more recent addition to the ever-expanding repertoire of thematic exhibition making, leading to such labels as a “sonic turn” in art.1 In the marketplace where the fetish for newness reigns supreme and where every concept that gains institutional traction inevitably suffixes its own “turn,” it is also the case that sound-as-art often starts connoting utopian qualities, like any medium in its embryonic stages. It is said that sound breaks through the material limits imposed on more conventional artistic media, that it dissolves boundaries, that it’s freer and more ephemeral. This is perhaps related to what the scholar Jonathan Sterne calls an audiovisual litany, “a conceptual gesture that favorably opposes sound and sonic phenomena to the supposedly occularcentric status quo.”2> As philosopher Robin James further explains, “the audiovisual litany is traditionally part of the ‘metaphysics of presence’ that we get from Plato and Christianity: sound and speech offer the fullness and immediacy that vision and words deny.”3 In other words, to mythologize sound is to say that it brings us back to an organic unity that has been overshadowed by the rationality of vision.

Such descriptions can also be found in the press release for the long-running exhibition “TUNE. Sound and Beyond” at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, where a monthly series of sonic interventions includes artists that present their work in various spaces of the museum: “Sound is the form of expression most easily liberated from its context: It can move freely through and between cultures” and “Sound … connects us to the ethereal.” Yet many of the artists participating in this exhibition view sound as an entity that is fraught with social, historical, and political implications, highly context-specific, and materially embedded. Featuring works by Lamin Fofana, Nkisi, Kelman Duran, Chuquimamani-Condori (Elysia Crampton Chuquimia) & Joshua Chuquimia Crampton, William Basinski, Abdullah Miniawy, Beatrice Dillon, and JJJJJerome Ellis, the sound in “TUNE” possesses characteristics that are likely to dislodge listeners and alienate them to a degree, rather than pacifying them with promises of mindfulness and self-identical immediacy.

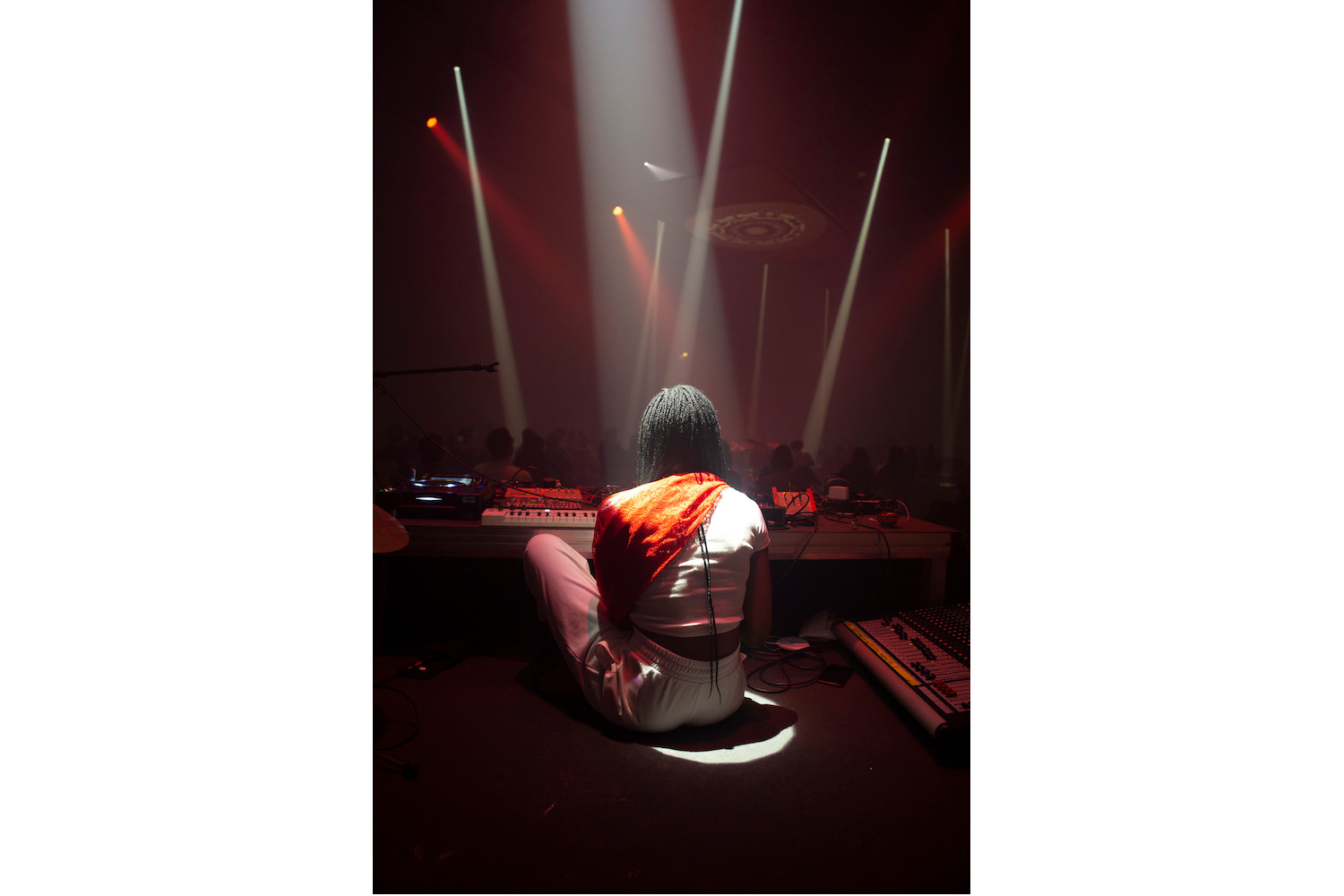

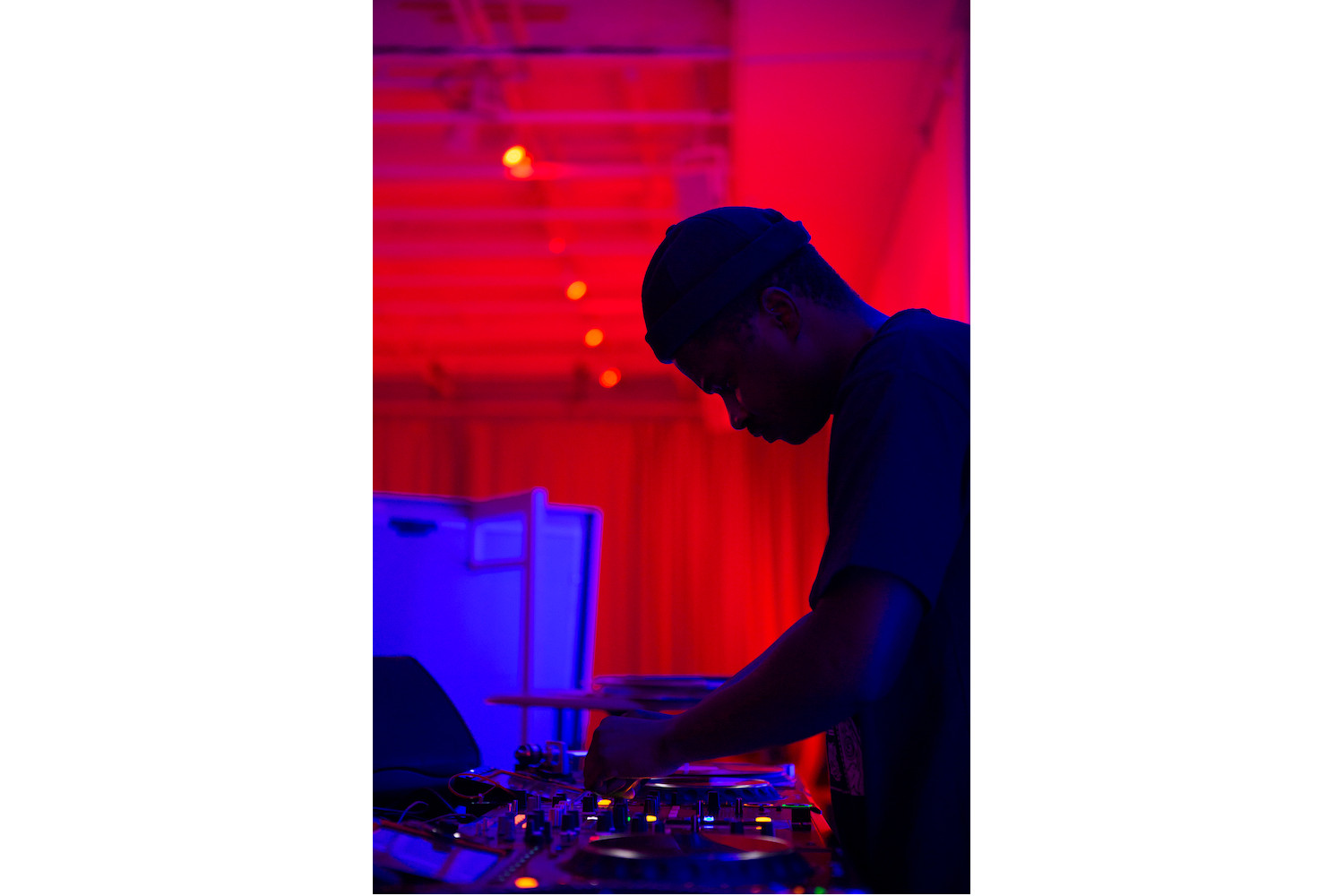

In addition to the monthly program, Haus der Kunst has launched a new annual sound commission that occupies the museum’s Terrace Hall. For its inaugural edition, music producer, DJ, and artist Lamin Fofana presents the installation a call to disorder (2021), inspired by the widely read book The Undercommons (2013) by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney. Oscillating between disorienting moments of abrupt intervals and lush soundscapes, the sound in the room, awash in shifting pink and purple light, does not retreat into the background, but confronts the viewer with sonic undercurrents, functioning as the return of the repressed of popular music production. As scholar Louis Chude-Sokei notes, “So much listening is actually the process of filtering things out. So much hearing is actually silencing.”4In Fofana’s installation, one indeed realizes that it is quite difficult to spend some time in a space dominated by sounds that are not necessarily purely “functional” (as is the case in a club, for example), sounds that we would normally exclude from our everyday perception in order to get rid of the excess disturbances. When we try to fully dedicate our auditory senses to what is “extra-musical,” we see how untrained our ears are to sounds that are not packaged in a narrative, socially sanctioned way.

As part of the program, musicians and composers Chuquimamani-Condori (Elysia Crampton Chuquimia) and her brother Joshua Chuquimia Crampton, whose sound is steeped in traditional Aymara knowledge and practices, gave a live performance interweaving acoustic guitars, synthesizers, piano, and spoken word, and screened the film Amaru’s Tongue: Daughter, in which they stage a ceremony for their grandmother and explore their family’s rituals surrounding death. Electronic musician, producer, and visual artist Nkisi’s audiovisual installation |Ngo| also reconsiders sound as an ancient technology. It consists of overlays of African rhythms and European dance tropes, where music is never just escapism, but becomes a rich reservoir of diasporic knowledge, mythologies, and cosmologies.

When the artists in “TUNE” emphasize the contingent nature of sound, its inherent porosity, it is to shatter preconceived notions of what an enduring model of Enlightenment-era aesthetic experience might offer, and to take us momentarily out of cherished notions of coherent subjectivity and linear temporality. But as can be heard in the works on display, such sound doesn’t spare us from the historical burden by pointing to a transcendent utopia; on the contrary, it plunges us right into it.