Douglas Fogle: About the mattresses…

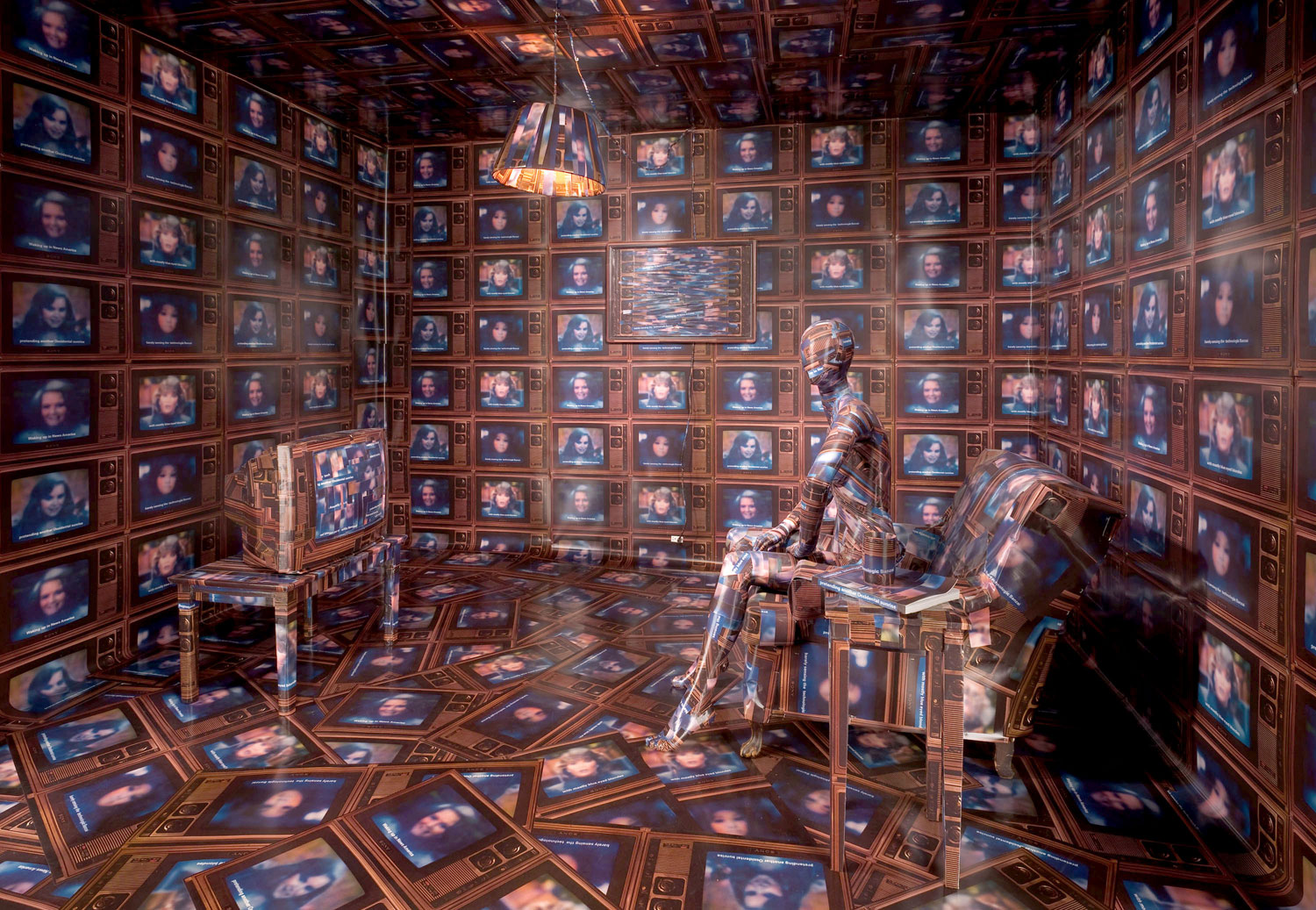

Kaari Upson: I saw them as this intermission, a project between two very large acts, a point of reflection. I knew that I was moving out of the Larry project for multiple reasons. I had spent so much time in a collapsed space, making work from that space. There was something forced so that’s where I stopped. The series of mattresses stemmed from an isolated mattress piece in my 2012 Carlson show. The latex mattress kept surfacing in my mind as something separate that could be projected on. Originally the mattress was a fragment of the entire latex room I made. Only after beginning the work did I understand it as a logical extension of my earlier preoccupations — another abandoned object that carried with it the people and events that had passed across and through it. It was made from memory and from a snapshot I took in Larry’s home before it burned down. The installation was a latex cast of his domestic space, which is comprised of fragments and flayed open, like a skin or meat. It was a piece that could be installed in a multitude of formations.

DF: You can take it and manipulate it and recombine the elements.

KU: Exactly, and so like most of my larger installations, they can transform, be broken, open, folded and collapsed. They should change every time they are installed. This constant mutability is an important factor in all my work. The mattress was free-floating, unattached to the larger installation that was one entire skin of the reconstructed room. At Carlson I decided to hang it, and it had this bodily feeling.

DF: You hung it on the wall?

KU: Yes, we hung it on the wall. It was completely deflated, a dead weight.

DF: The subsequent mattresses are incredibly anthropomorphic. Of course a mattress is the measure of a body. One thinks about Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s very famous image of the bed with the covers pulled back and the indentation of the bodies that are no longer there. It is in fact a really incredibly anthropomorphic and resonant piece for thinking about the body. So your use of the mattress really made a lot of sense to me.

KU: These ideas were already present in previous works, even the smoke paintings (2009–12) and the charcoal tablets (2010–12), which had the impression of my body made in them through the experimental mold-making process. The charcoal tablets had a very similar process of working blindly, where I made impressions based on physical movements I had developed in a previous work, Four Corners, which I started in 2011 and worked on for a year. In that work I was breaking down the charcoal body, which was part of another previous artwork…

DF: A performance.

KU: It was a performance, but private, in my studio.

DF: A therapeutic ritual?

KU: The charcoal body I used in the performance weighed as much as a real body or more. When I originally made those sculptures, I made them so that they could be destroyed or rubbed out. I kept thinking about “When is done, done?”

DF: It could be abraded or eroded?

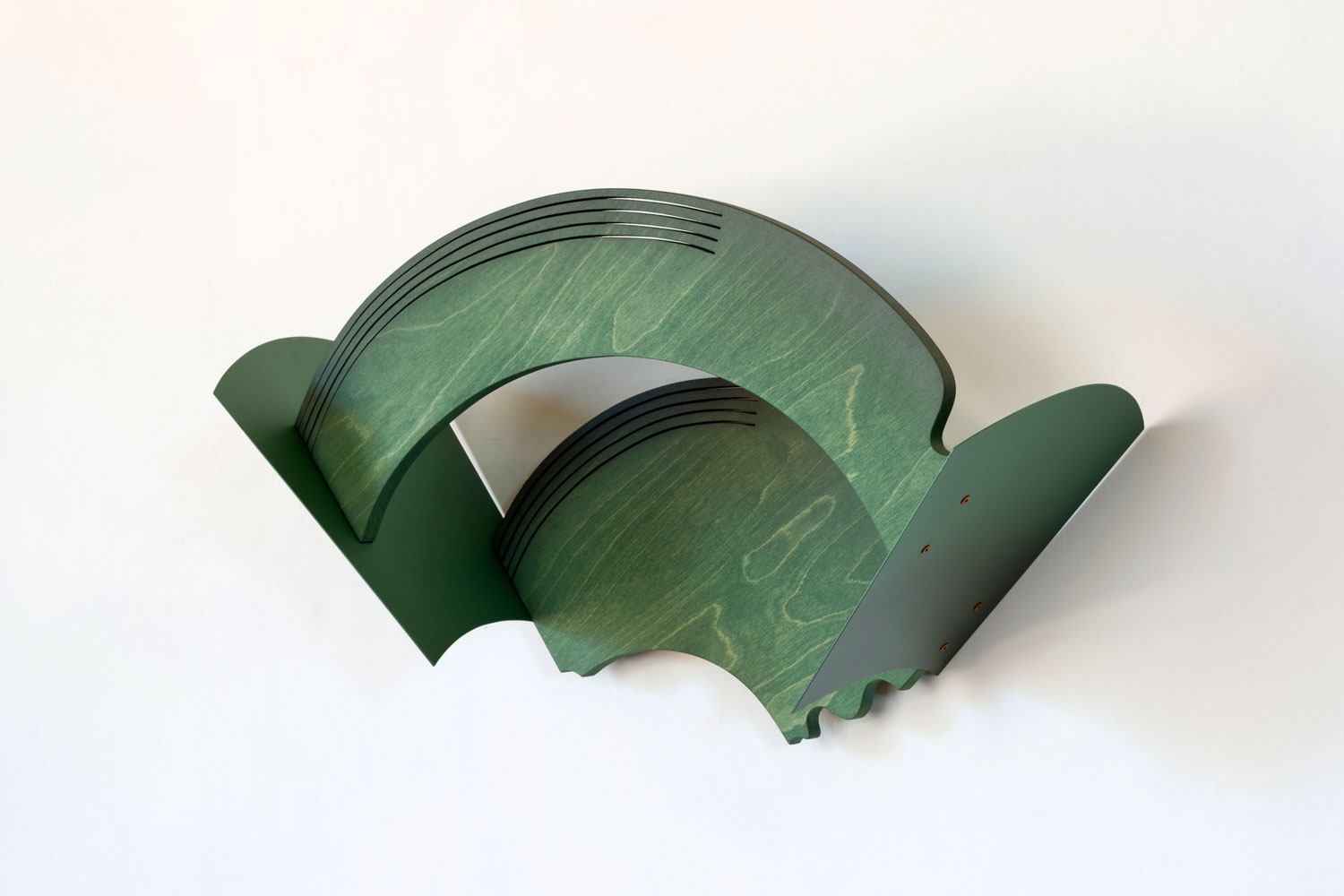

KU: I wanted to move a sculpture into a drawing and then dust. And since it had a weight to it, I was limited as to how I could do that. My body could only lift so much. I started to realize that my gestures, the gesture of lifting 225 pounds [102 kg] and trying to break it, started to create repetitive actions. What was interesting was that the box itself wasn’t of importance as a sculpture. It can come apart and come together in different ways, but what I learned in that space was that these gestures started to form their own language. I tried to translate them directly to the charcoal tablets.

DF: Did it feel like a kind of organic choreography with your drawing practice becoming physical, three-dimensional or incarnated? The medium of your drawings was charcoal, but the charcoal then became the object. You’re reversing the process in an interesting way. It’s similar to choreographers drawing out movements on the floor. It reminds me of Warhol’s dance diagram paintings.

KU: Joan Jonas was a huge influence too. Also Robert Wilson.

DF: Or Bruce Nauman’s early video performances in his studio like Slow Angle Walk (Beckett Walk) (1968) or Bouncing in the Corner No. 1 (1968). You’re looking for movements or patterns.

KU: Hunters do this all the time. It’s the idea where you soft focus, so that you take in the entire visual field. I’ve always thought that if you back off of your subject that something you wouldn’t normally see would be caught. And rather than overthink the fact there was almost nothing, as if it was a self-generated box, I just extracted what was already happening, which was just one gesture after another. And I thought about how I could record that. The way I went about it was by using a very similar material to the actual sculpture itself that was being destroyed.

DF: Charcoal?

KU: Yes, but in a different way than the charcoal body sculptures. I thought about the fact that it was a document. I wanted to capture a movement in a static way like a photograph. It’s still charcoal but I changed the binding agent to something that would freeze, almost like plaster. I had to work with a very unusual mold-making process to make the impression. The gesture would be made on these beds. This soft surface with a thin layer of aluminum covering it like a sheet could record the gesture, touch and movement. Then the aluminum would be peeled off and reveal the frozen charcoal document. The mold would be destroyed in its process, so they were all one of a kind.

DF: They were the equivalent of a monotype.

KU: Very similar to monotypes, yes. But still, within that body of work, which I saw as “panels,” they existed by leaning against the wall, there were repetitions.

DF: Because the gestures were repeated over and over. There was difference but there were repetitive gestures that led to a certain type of unintelligibility.

KU: Looking back on it, it was this relationship to the body and the mattresses. All the smoke paintings I made were made from four-by-eight-foot [121 x 242 cm] panels, because of their relationship to the body.

DF: The measure of what a human being can actually move.

KU: Exactly. So it continued through the charcoal panels and the box. There is always a system in place, as chaotic as it is. It’s true that I’m really keen on not knowing what’s going to happen. I am always interested in preserving the unknown in both content and form. I leave at the point when something starts to become mastered.

DF: As a transitional body of work, but yet a body of work unto itself, the mattresses become a logical extension, in a way. Regarding your choice of charcoal I started thinking of the fire at the house.

KU: Absolutely. The charred beams that I extracted early on were real beams from the real house.

DF: You were doing your own archaeology.

KU: My first installation ever was in grad school when I laid two of these charred beams one on top of another. They looked like bodies. This came back several years later in my installation at Maccarone where I placed two charcoal bodies on top of each other. But these were made from a long process of casting a soft doll that I had worked with earlier.

DF: Charcoal is one of the most primitive drawing instruments. You burn something but then you can make a mark with it, a human mark, an index, a palimpsest, however you want to think about it. There is an ephemeral side to that process, but then you’re freezing it with the binding agent. In my mind, drawing is clearly the fundamental basis underlying everything in your work.

KU: In my studio, you once talked about my drawings being the unconscious mind of the sculptures. The drawings are the beginning, middle and end for each project. It’s how I map it out. It’s how I remember. It’s how I locate myself. I learn more through that process than almost anything else. I can give so many examples of things that I came to through the drawings. When I started to think about rebuilding the house that no longer exists. And all of the gaps between the information I had. But I always knew that I was going to get to the endpoint where I would have to deal with the house as a subject. And at that point there was no human element left as the house had been burned down for several years. After it had been razed I tried to obtain the original blueprints, but for some reason this house had no blueprints. I went to the site and found nothing. I sat down in the dirt, and I started to realize what was there.

DF: It’s a bit like forensic anthropology or archaeology with their scientific rigor, but there is something equally uncertain in the work with its embrace of an almost Cagean notion of chance. There is something beautiful about the flexibility, unpredictability and lack of mastery in your work.

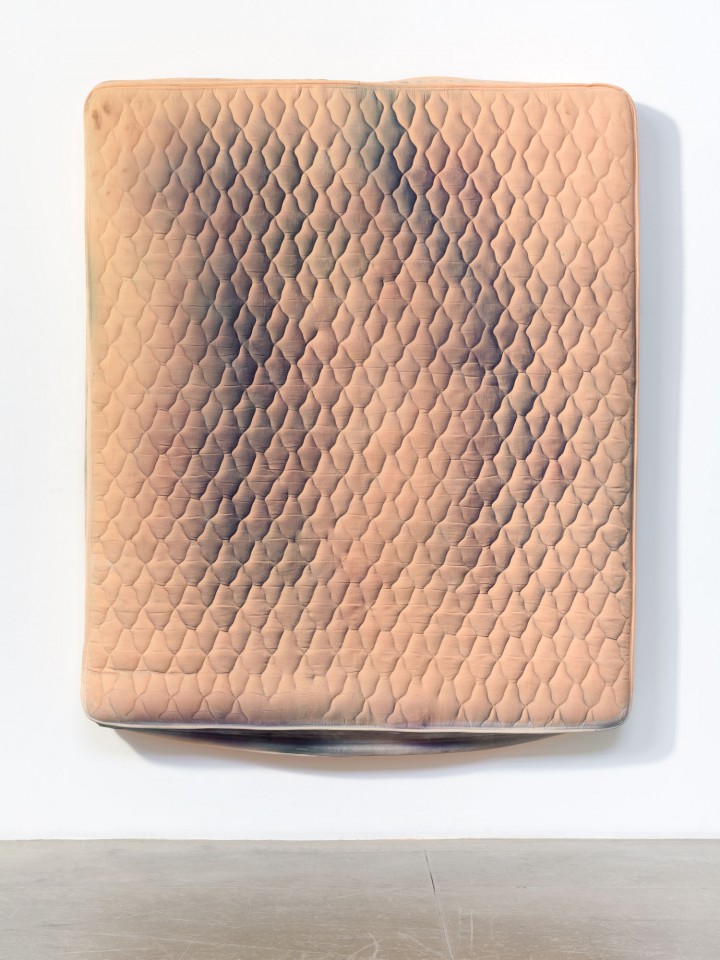

KU: Yes, with the new mattresses these felt completely that way. They were so physically demanding to make and I had to work blindly because they are poured into a mold. I made these by casting discarded mattresses found on the streets of Los Angeles. I am very interested in their stitching and fabrics that are made to camouflage the bodily fluids of years of living. These are now artifacts of disease. They are co-opted abject things that I can now map over with painting’s history. They are a conflation of representation, abstraction, abjection and the status quo of painting because they are casts of a real thing, down to every stitch.

DF: And also representational in the sense that they are portraits of the unknown subjects who once inhabited them.

KU: They’re surprising. I’ve never worked on anything isolated like that. I work in multiple directions generally, and in any medium that best suits the idea. When the mattresses came about, I realized that in order to make them correctly they needed my full attention. The second you start one of these silicone works they have to be finished in the same span. Nothing can be stopped. They evade any kind of natural handling. But I like that they exist as durable burdens, in a way.

DF: It’s like a team sport, whether it’s soccer, football or basketball where the choreography of the movements have to match, or you have to adjust them on the fly. And that’s also why I brought up dance. But that would be more along the lines of contact improvisation or something where there’s more flexibility and more reactive qualities. Because you don’t know the volatility of the medium of the body or in this case silicone. Obviously dance choreography is all about control, precision and repetition. What you’re saying is that you couldn’t do that in this. You were repetitive in certain motions and certain things. But at the same time, the time frame in which you were making this work is predicated on the volatility of the material.

KU: The option of scale was taken away from me. I don’t even get to make a decision on the scale of the work as its starting point because it’s already predetermined.

DF: It’s a bed.

KU: It’s a crib bed. It’s a twin bed. It’s a bed. Even when we get to the king bed, it never gets to a monumental size. It’s the most domesticated one-to-one part of our lives. There is also the issue of how to determine when the work is finished because I start with the initial mark but by the time I start to build up the silicone it’s finished because the structure is finished.

DF: It finishes itself. Were you looking at the poured sculptures of Lynda Benglis? They were also incredibly time-based. Functioning as paintings, they also function as anti-paintings. I would say the same about your smoke paintings and the beds. These are paintings by other means. It’s another answer to the death of painting, as in, “Now what do we do?” Because painting is not dead; it’s the “but, and.” But painting is dead, and we continue to paint. It’s very Samuel Beckett. I can’t go on, I must go on.

KU: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.”

DF: That’s the magical moment, right?