I’m on the phone with artist Tosh Basco, explaining how hard it is to write about her work. “Well, I’ve always felt very locked out of written and verbal language,” she tells me, sympathetically. “It sounds strange, but I was probably in my mid-twenties before I really felt I really read a book.”

Basco’s work is fundamentally about this kind of intransigence. In its manifold forms — she works across performance, works on paper, and photography, as well as consistently collaborating (with the interdisciplinary artist Wu Tsang; as a cofounder of performance group Moved by the Motion; in the films of Korakrit Arunanondchai; with Sophia Al-Maria; and others) — it addresses ways to find forms for the inexpressible, to explore what happens outside languages, and in between them. Paradoxically, you actually find language throughout Basco’s work: not on the surface, but deeply buried, as an obstacle. Like biting into a fruit and finding a hard stone between the teeth.

Born in California in 1988, Basco has been performing, under the name “boychild,” for more than a decade, and presenting in contemporary art spaces for almost the same time. But, she explains, she never sought the spotlight: at least, never with a sense that it was a space she’d feel at home in. The genesis of her performance career was in fact a confrontation with “fear.” A friend, Justin Kennedy, then studying dance in Berlin, invited Basco among others to create a character to perform for his thesis piece. “He was the only person who I felt safe to dance with, was more about dancing together than being seen,” Basco says, explaining how unnervingly the invitation sat with her. But she did it anyway, and held onto the skill “of following the terror of something that I wanted to do.” Returning to California, the question she faced was: “How am I going to show up to this desire that I have?”

The form she found to show up with was the lip-synch. A staple of drag entertainment in the USA, lip-synching is traditionally a silent mouthing along to an existing sound track, a matter of coordinating body and sound seamlessly, one to one. As boychild, however, Basco turned the form into something wilder and more abstract, opening up a wider gap between text and interpretation. Instead of taking song lyrics as a set script or score, she instead approached the form as one that “allowed me to use a text-based work — an essay, a book, or a poem — and bring that into my movement.” So a word could not simply dictate the shape of a mouth, say, but become “a movement, a color, a feeling.” The resulting works are palimpsests, layering text, sound, light, and “embodied performance” in what the artist refers to as a “composition of meaning.” “You put things together,” she says, with disarming simplicity.

In this way, Basco places these works in the lineage of the radical underground music she experienced through queer nightlife. “There are certain DJs who taught me so much about dance,” she says, comparing the way a remix can combine two genres of music with how a performer might “remix” different traditions of dance. Audiences likened boychild’s performances to the works of British drag artist Leigh Bowery, and the avant-garde Japanese postwar genre of Butoh. In each, Basco admits, she sees a common thread of performance as responses to crisis and hostility: sui generis explorations of “what it means to survive in the space of violence.”

Online, I watch a video of an early boychild performance, Untitled Lipsync #1, from Glasgow in 2013. The performer is lit by two strobes, flickering at either side, with a white LED light in her mouth. She is performing with a shaven head, breasts exposed, skin powdered white. She is standing on a small platform covered by her long skirt, giving her an artificial height, and making her one with the plinth. She appears not fully human, like an antique sculpture come to life (I thought of the great Lorenza Böttner’s performances as the Venus de Milo) or an android, uncovering some new and frightening possibility in its coding. In the words of scholar Jack Halberstam, boychild’s movements typically “combine slow and grotesque precision with fast-twitch convulsions, making it unclear if the body is breaking down or struggling to be born.”1 By the time the artist debuted Untitled Hand Dance at the Venice Biennale in 2019, a work which I watched snatches of through the rain in the Giardini, the lexicon of movement had been refined into a sequence of stuttering jabs and stretches, fluttering fingers, and fragile body twists. The absence of a soundtrack only heightened the sense of precarity. “If she stops moving,” I remember thinking, “she’ll start crying.”

What these performances are getting at, I think, is a kind of catharsis. They remind me of the oft-quoted passage from poet Anne Carson’s translations of Euripides: “Why does tragedy exist? Because you are full of rage. Why are you full of rage? Because you are full of grief.”2

In 2021, Basco began exhibiting works on paper: abstract, gestural, seemingly not so much consciously composed as emerging from a painful frenzy. Many seethe with color — green, purple, gray-blue — the colors of a bruise turned fascinating. Often, paint appears to have been dragged across the surface by the artist’s fingers, while other patches suggest more smudgy moments of skin contact with graphite, pigment, and paper. The works are registers of movement, testimonies to a body’s undepicted presence. In this way, they could be likened to fevered cover versions of David Hammons’s “Body Prints” series (1968–79) or, per the title of one work in “Angels, Hand Dances and Prayers” at Company Gallery in 2021, the Body Tracks (1982) of the late Ana Mendieta (scrawl for Ana, 2021). It’s as if the artist is seeking an alternative kind of performance documentation to the photograph or film, one in which the forms of the movements are crystallized, but the shape of the body is obliterated. In this way, the viewer comes closer to “seeing” the performance not through the external form of the performer but as boychild/Basco might, from within. Instead of a corporeally legible figure, a synesthetic blur.

Perhaps this pivot resulted from a reaction to the growing circulation of images of boychild’s performances (Basco was also, at this time, a kind of unofficial muse to the cult fashion label Hood by Air). The artist says she sometimes feels a photo of a performance “kills it.” Just as the map is not the territory, so the document of the performance is not the work. “I can be distrustful of an image,” she continues. “A photo can be a lot of things, a portal, or a window, but it’s also a grasping.” In the circulation of images of boychild’s performances, Basco sensed “people trying to grasp what they were seeing” — to pin down her identity perhaps as an entomologist might a butterfly. With the works on paper, Basco offers wavering demurral in place of certainty, her marks forming nebulous little clouds of unknowing.

Talking of the way ambiguity can be buried under “identarian language,” Basco admits, ruefully, that “if you want to reach a mass of people, there will be things that are lost.” So, while the title “Grief Series,” shown at Karma International, Zurich, in 2021, nominally referred (per the press release) to the artist’s “personal incidence of grief,” I wonder if these works are also about mourning another kind of loss: of that which vanishes in transmission, in translation, from text to performance, from movement to mark making. Grief, like all intense feelings, eludes language. Weep, wail, beat your chest, rend your garments: something unspeakable remains. Where does it go?

When Basco describes what she values most from her performances, it is in terms of their affective afterlife: “When I meet someone years later and they tell me, ‘I saw you in Chicago!’ or ‘I brought my mum to this gig,’ and they remind you of a feeling.” Her description, to me, recalls the way photos so often function: to freeze a moment in time, to hold a memory, still.

Even as a twelve-year-old, Basco wanted to become a photographer; she learned to shoot on a Canon camera gifted her at age fifteen by her father. But as she developed as an artist, she became suspicious of the medium, of the “violence of capture innate to the mechanism of photography” and its embedded history of image-making as a political tool for the granting of “subjecthood,” indexing identities, surveillance in the name of representation.

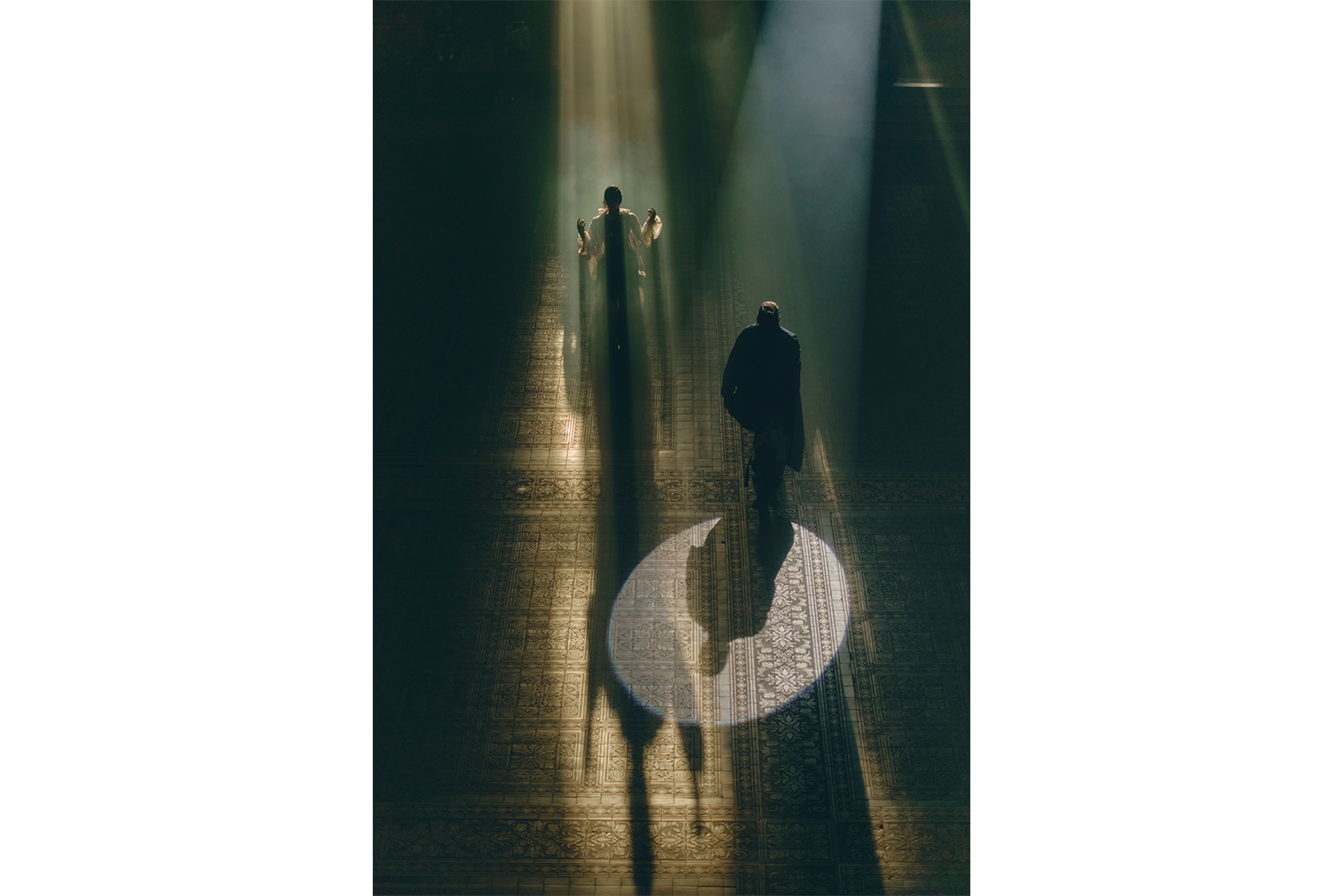

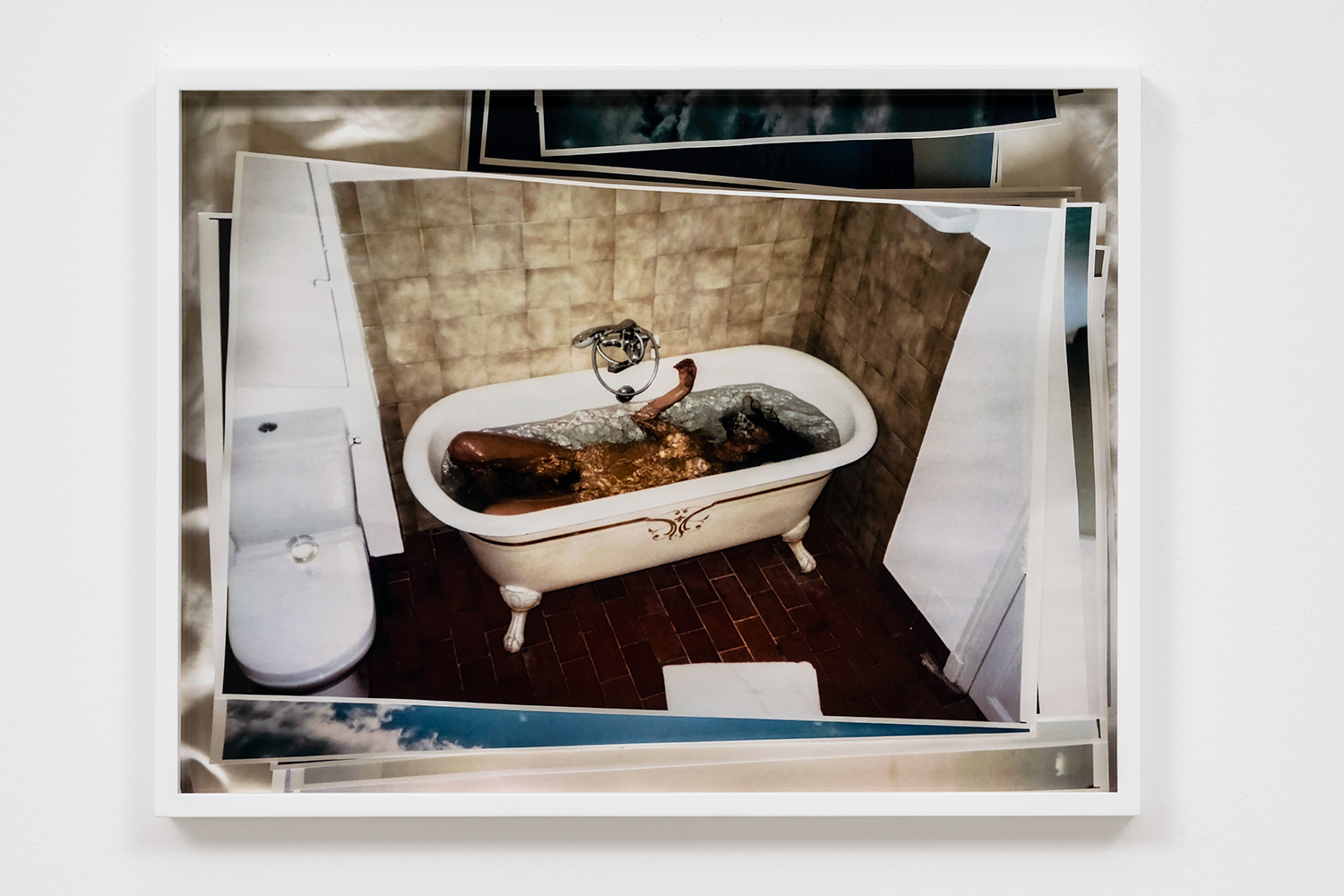

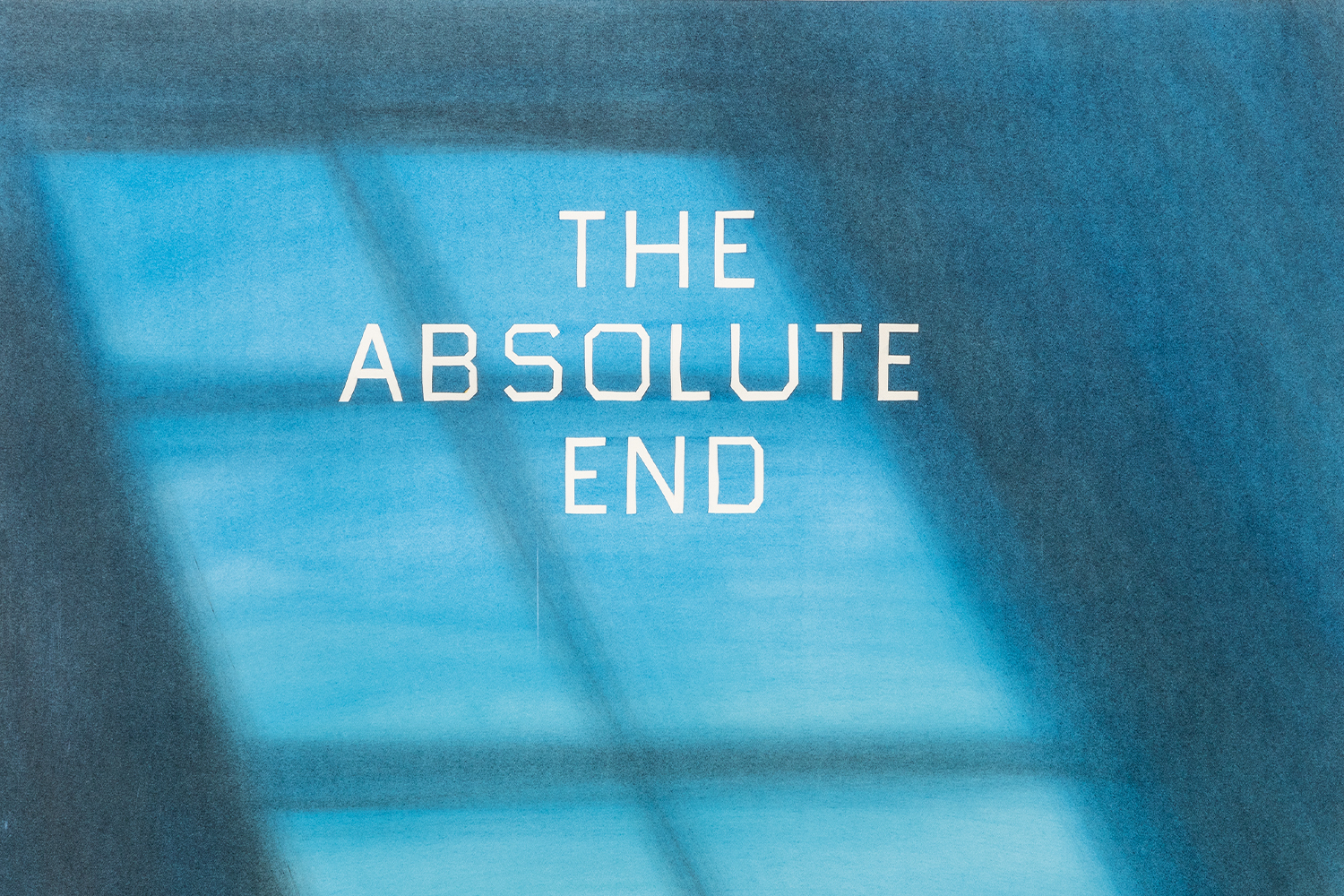

Still, the photographic impulse resurfaced, like the return of the repressed. “Photography is the way that I grapple with my own sense of memory and my personal life,” Basco explains. “I take hundreds if not thousands of photos a year.” In 2021, Basco presented “Portraits, Still Lifes and Flowers,” a suite of twelve photographs at Carlos/Ishikawa in London. Each one captures a stack of countless photographic prints, only the topmost one visible, like the first card in a deck. The images caught in these frames-within-frames are commonplace stuff: a view through a window, a lover under a sheet or submerged in a bath — and cut flowers, in various stages of drooping, wilting, rotting. In this way, they speak the quiet daily grief of living, and the constancy of change (note the mutability of light in the pictures, from early morning glow to late night flash). A sound piece was available for viewers to listen to as they viewed the pictures, adding a dimension of duration: a reminder, too, that time is always present, always passing.

When I first saw this show, it was hard not to view these works (all drawn from photographs taken in the preceding two years) through the lens of the COVID-19 pandemic, when loss was all around us, time did strange things, and, mostly housebound, the scenes that accompanied many people’s experience of historic events were not epic, but domestic.

But through the metaphor of the stack, it seems to me, the works also speak to a more general condition. In the way that only the topmost print in each pile can be seen, the archive of experience buried below them made inaccessible to the eye, they remind us that remembering often comes at the price of forgetting; that to hold one thing visible is to obscure another. How, faced with a daily torrent of images, our inner memory cards are, so speak, always almost full.

Toward the end of our conversation, Basco tells me about the author Marguerite Duras’s account of watching the news on French television of Michel Foucault’s death. Duras observes how newsreaders “announce an earthquake, or a bomb attack in Lebanon, or a bus crash, or the death of a celebrity. But you’re in such a hurry to get to the laughs you’re already in fits over the bus crash.” Basco says she’s been thinking about this passage for years, and how, with the convergence of mass media, photojournalism, and social-media feeds, the deadening chaos of Duras’s experience is now constant, intensified. She recounted seeing videos of California burning and then, next, a photo of a friend walking in a fashion show. “The television news bulletins are a riot from start to finish,” writes Duras, “and you have a nervous breakdown.”3

“I think about portals and windows and frames and stages. I think a lot about the body as a portal, how there’s so much meaning that goes in and out, there’s so much interface of world and violence, or love or care. And I have no idea how to encapsulate all of it.” I don’t know either, so I’ll turn back to where we started, with language, and its difficulty, and a line from the poet Robert Lowell. “Though burned, you are hopeful, accident cannot tell you / experience is what you do not want to experience.”4

What can’t be told, it implies, must be felt. And to feel, I think, we have to carry on.