In her 1975 poem “Liebestod,” Gwen Head writes of a girl on a beach who sunbathes with a glittering gun beside her. She is saved from some unknown war by a paratrooper dropped from the heavens: “Here at last / is love to set the world on fire.”1 And on fire it is, with hard nipples and dreams of disappearance into the sunset, when of course the sunset has long faded. In the place of natural light are the fireworks of fascism. Head’s poem refers to Richard Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde — more specifically the final sonic movement titled Liebestod, which translates to “love death” in German. The poem’s titling therefore suggests that there will be no consummation for the ingenue and the paratrooper — that the narrative will end abruptly with a bullet whose penetration we invited on that beachy wasteland. The aestheticization of war is a fascist operation (Wagner later became a Nazi favorite), but it also represents something we might want — to know that all this suffering was worth it, to get fucked to death and then saved in a blaze of glory again and again like and with those clichés onscreen.

Nicolas Winding Refn’s Too Old to Die Young, which premiered on Amazon in June, lingers like the lovestruck and armed girl, and Refn, like Head, commands the sentimental landscape instead of (and in addition to) being a symptom of it. The series, which Refn actually considers to be a film, languidly follows a dirty cop, a Mexican crime boss who lives for anal sex and avenging his mother, a social worker who moonlights as a hit woman/mystic, and the High Priestess of Death, who metes out justice on behalf of abused women. At this point, to say that any object of culture is avant-garde merely by virtue of eschewing narrative or normative character development is superficial and pretentious. What could be more revolutionary at this point than narrativity that is unconcerned with itself as such? But isn’t that everything that Donald Trump represents in the most conservative fashion? Where do hope and hubris intersect? More interesting than the skepticism inherent in the suspension of disbelief (there is always the gnawing thought that we are being bamboozled or mocked) is the simultaneously radical and complacent investment in belief. The belief cultivated by TOTDY thrives within despite — and because of — the alien intimacy afforded by a dust storm of archetypes that blows in exactly when we feel the most desiccated and barren ourselves. Both genre and archetype, in giving us ways of organizing the ongoing messiness of our lives, can be liberating exactly in their confining nature. TOTDY surprises us with things we have seen before — not by denuding repression or presenting us with ironic uncanniness, but rather by offering the cliché with compellingly hysterical earnestness.

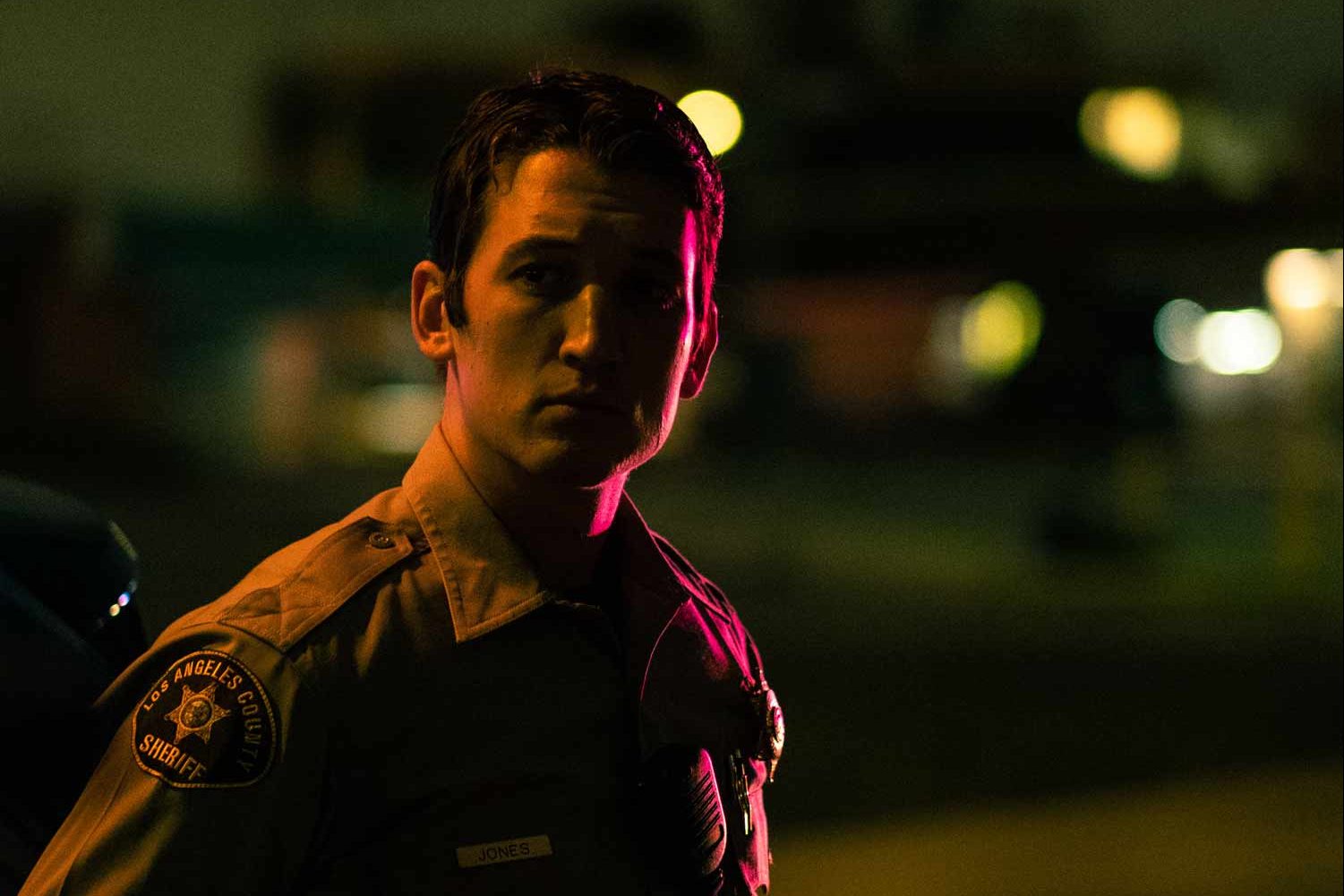

For the purposes of an introductory essay, I can attempt to appeal to narrativity for a moment. A stoic cop named Martin Jones (Miles Teller) sees his partner executed by Jesus Rojas (Augusto Aguilera), the son of a female drug lord who was murdered by the police (perhaps by Martin himself). As Jesus returns to Mexico to rebuild his mother’s empire, Martin dedicates himself to a life of vengeance upon the truly evil. To this end, he joins the cruel and sympathetic hit man Viggo (John Hawkes) and his mentor Diana (Jena Malone), a social worker who determines which individuals are most worthy of death — mainly those who abuse children — in her case files. Meanwhile, Jesus marries Yaritza (Cristina Rodlo), who claims to be the High Priestess of Death, and returns to Los Angeles with her in order to regain the territory that had been stolen from the cartel. My partner Felipe L. Núñez, in watching the series with me, concluded that these shifting and unexplained nexuses of power have everything to do with the hegemony of the streaming industry. Refn might even see a link between the concentration of artistic capital in a few monopolistic hands and the Trumpian melodrama that has truly become a Kardashian-era fairytale of good and evil. What could be more of a cartel, after all, than Amazon, and who would be more suited to critique it from the inside than Refn, whose relationship to the financial and creative structures of the film industry has always been precarious?

Criticality and subversion, however, seem simultaneously irrelevant to TOTDY’s louche and lurid characteristics, leading many critics to deem it self-indulgent. So, I wonder, what of Head’s lounging Bond girl? What is she thinking about? Is she deconstructing her sandy consummation or just enjoying it? At the same time, the anti-interpretation argument has been made, and probably made better, by Susan Sontag and others, so we arrive at yet another cliché, another melodramatic convention of the writer with nothing to say. With nothing to say themselves, writers turn to history and discourse, the perpetual outsides, for help. If self-indulgence has become understood by some critics as a convention of Refn’s films, we could also say that self-indulgence is a hallmark of convention and genre anyway. When experiencing the narrative slowness of TOTDY, oft remarked upon by critics, I kept recalling Chantal Ackerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, which premiered in 1975, the same year Head wrote of grenade-like breasts and handsome airmen. Ackerman’s feminist realism finds its truthfulness exactly in its “self-indulgence,” in every meatloaf Jeanne Dielman prepares or in the linen she folds. In a way, the film’s labored aspiration to truth is not that different than films for which Refn has actually expressed admiration — exploitation films and B-movies. Is it perverse to compare Ackerman’s protagonist folding an egg into a pile of meat to that senseless and purely self-indulgent turtle murder in Cannibal Holocaust? I do not mean, of course, to suggest that Ackerman’s feminism is ethically comparable in any way, but I do want to think through how all those filmic conventions of emotional repetitiousness — kneading, hacking, staring, soliloquizing, fucking, bleeding, driving, loving — amount not to something clichéd, but rather to something we have never seen before. All film aspires to be truthful, and yet that truth is built upon a series of actions that are at once rote and imbued with agency. Head writes in “Liebestod”: “The earth does in fact move for this conjunction,” and I think this sentiment might also drive Refn.2 TOTDY, in its insistent recalling of genre and conventionality in each episode, makes a conjunction radically available to us. It is a space wherein “and,” “but,” and “or” coexist, wherein multiple events and multiple dreams appear to happen at once. This is perhaps the dream of the melodramatic genre as such — to fill the world with so many markers of emotional legibility or emotional realism that art and life finally merge at last. Indeed, all genre is an organizing force that hopes to give our boundless human emotionality something to hold onto, something to stand alongside. We can use genre to critique or we can use it as a companion, and we may use it in its endless iterations in order to give shape to our own lives.

We could say that TOTDY is a kind of pastiche, but that word connotes imitation rather than emulation and becomes too quickly linked to parody. More appropriate might be “montage.” Refn, like Hannah Höch, Martha Rosler, or Lorna Simpson, is sentimental about the stuff of film and the emotions it provokes even as he rips its guts open like the slain turtle. TOTDY lays bare the mechanics of how we come to identify with and love film and television, but that deconstructive or critical end is not all there is. Refn additionally creates a landscape of choice in which we can get, to paraphrase Douglas Crimp, the melodrama we deserve, or, more specifically, the melodrama we need. We might approach it ethically, formally, narratively, erotically, or all or none of the above. It is also worth noting that I think Refn’s reformulation of genre is rather different than David Lynch’s, which always feels more self-contained, more hermetic, and less concerned with whether the audience can step into the world onscreen. For better or worse, Refn, I think, is dedicated to a populist approach rather than auteurism. In this spirit, Refn and Head place us in the war, on the beach, in pornographic ecstasy. TOTDY concludes insistently and unexpectedly with the world on fire in each episode, thereby refusing narrativity despite its queerly masochistic love for it and ending ultimately with a poetic anti-manifesto akin to “Liebestod.” The era of manifestos and counter-manifestoes is indeed over, but Refn nevertheless wonders, I think, what it is to continue to imagine the world archetypally, as a series of pleasurably melodramatic spectacles. He thereby presents us with an array of emotional and sociopolitical superstructures as such, rendering them thereby both intimate and foreign to us, both revolting and erotic.